Stay Pareto efficient and keep the cameras on.

There are a lot of inconsistencies in my life, but one thing remains the same; 20 seconds before my class begins, I hop on the “Zoom Class Sessions” tab on Courseworks, click on the class zoom link, and am immediately presented with a dilemma. I am asked whether I wish to enter class with my camera turned on or off. For most people, the answer is obvious: off. But I implore you to consider why you might want to enter with the camera on.

I labeled this camera situation as a “dilemma,” but that is a simplification. What we are dealing with here, is a prisoner’s dilemma. For those of you who have never experienced the glory that is Intro to Economic Reasoning (shoutout Professor Archibong), I will do my best to explain what a prisoner’s dilemma is. Take, for example, a situation in which two people (Person 1 and Person 2) are caught for allegedly robbing a bank. Both criminals know that the police only have enough evidence to charge both of them with one year of jail time. But, if Person 1 confesses to the joint crime while Person 2 remains silent, Person 1 will go free and Person 2 will serve five years of jail time. The reverse is also true. However, if Person 1 and 2 both confess, then they will both serve three years. There is no collusion and no repetition of the game; there is only one shot at either confessing or remaining silent. In this scenario, players typically act out of their own self-interest, leading to a less optimal outcome than if they had acted in a more cooperative manner (i.e., both receiving three years vs both receiving one).

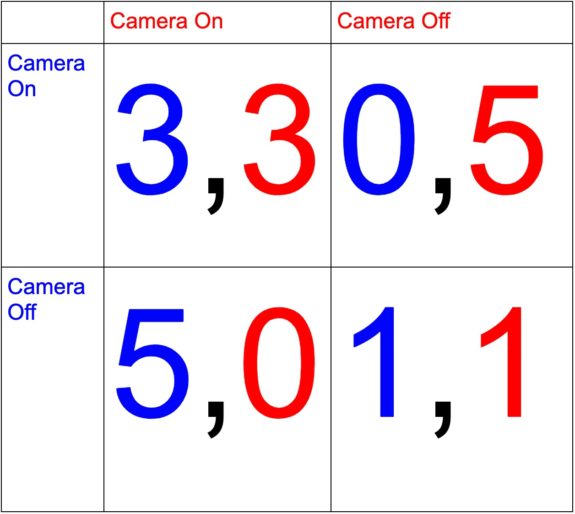

If neither the words “economics” nor “prisoner’s dilemma” have yet to trigger your cognitive dissonance, then you may be wondering how a prisoner’s dilemma is relevant to Zoom. Consider how the decision to come with your camera on or off is another version of the prisoner’s dilemma. It is a one-shot game where participants’ actions are unknown and entering the Zoom happens only once (a one-shot game). Looking at the payoff matrix I made below, we can see that the dominant strategy for each player is to come in with their camera off. Unlike in the example above where the numbers referred to time spent in prison, the numbers in the matrix represent the payoff: the higher the number, the greater the benefit. The numbers are arbitrary, but, at their very core, demonstrate the gains and costs associated with arriving to class, the camera turned on.

Player 1 entering with their camera off while Player 2 has their camera on leads to a higher payout for Player 1 since Player 1 is saved the embarrassment Player 2 currently experiences. Conversely, Player 2 is embarrassed that the only face they are staring at is their own, so there is virtually no payout. Player 1 and 2 both arriving camera-off leads to a lower payout than both coming into class with their cameras on because the latter fosters human connection and simulates a real classroom experience: it is nice to see one another.

As seen from the matrix, when both players choose to arrive camera-off, they are playing their dominant strategy, but the outcome (1,1) is a less socially optimal outcome than both arriving cameras turned on (3,3). So, to throw in some exciting economics vocabulary that you can now casually insert in conversations to seem smarter (not unlike what I am about to do), we would say that (1,1) is a Nash equilibrium. (1,1) is a Nash equilibrium because there is no incentive to deviate from the employed strategy. However, (3,3) is the only Pareto efficient outcome because it is the most socially optimal (no one can be made better off without making someone worse). All this to say, if everyone were to arrive with their cameras on, then we would all be a more productive society! We would also make our Professors happy because of how discouraging it is to look at a bunch of turned-off cameras. Keep your cameras on and stay Pareto efficient!

so i guess this is economics via Picpedia

0 Comments

0 Comments