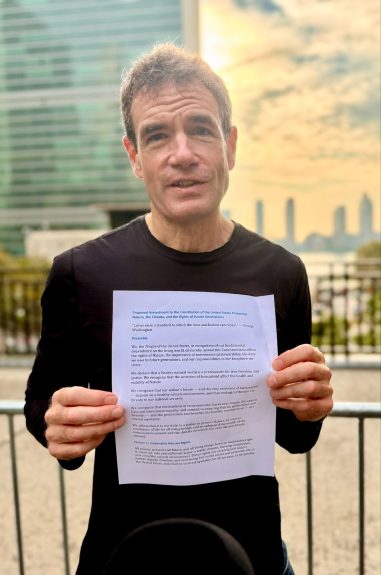

On September 24, environmental advocate Christopher Swain stood outside the United Nations headquarters and proposed a Constitutional Amendment to “protect the rights of nature and future generations.”

On the morning of September 24, during Climate Week, environmental advocate and open-water swimmer Christopher Swain (Climate School ‘26) stood outside the United Nations headquarters to launch a campaign for a Constitutional Amendment to “protect the rights of nature and future generations.” The full text of the proposed amendment can be found on Swain’s website.

This campaign was launched in response to the United States’ withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement, an international treaty signed in 2016 to keep global surface temperature increase below 2°C above pre-industrial levels.

“This amendment is dedicated to all my ancestors, and to all my descendants,” Swain declared. “It is for my children, and my children’s children. Yet what I hold in my hands today is more than an amendment. It is a prayer for America: May she be forever wild, beautiful, and free.” Swain then unveiled the proposed amendment and read it aloud, marking the beginning of what he envisions to be a collaborative campaign.

Swain, who has swum in some of the most polluted waterways in North America, sees swimming as both a platform for storytelling and a tool for advocacy. His activism began in 1995, when he read the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and realized that much of what it called for remains unfulfilled. To raise awareness, he walked across the state of Massachusetts, handing out copies of the declaration to draw attention to the declaration’s promise of universal human rights. The following year, inspired by that experience, he swam 210 miles down the lower Connecticut River in support of the declaration. By swimming, he found he could spark meaningful discussions about water pollution and the right to clean water.

He had originally intended to announce his proposal for a Constitutional Amendment during his planned swim of the full length of the Delaware River next year. However, he decided instead to begin the conversation earlier, inviting public feedback from students and faculty members ahead of a more public campaign.

Last year, Swain began studying how other countries incorporate environmental protection into their legal systems. He was particularly struck by France’s environmental charter, which was added to the French constitution in the early 2000s.

“They recognized it was in the socio-economic interest of the country to care for the planet,” he said. “They made it part of the constitution… Our founding fathers [referring to the American founding fathers] never anticipated this level of environmental destruction.”

Swain believes this is a conversation that must involve everyone, not just environmentalists or academics. He has had conversations with fishermen, people on the alt-right, and others who don’t necessarily identify as environmentalists, yet he’s found ways to frame the issue around the climate and the future of America in order to find common ground.

For Swain, the work is as much about personal growth as it is about politics. “I want to be the kind of person who’s courageous enough to push it into the public space,” he said. “When someone does something—even one person—it gives other people hope […] Your generation will be the heroes who succeed or die trying […] I’m happy to be at the beginning of this moment.”

When asked about his next steps, Swain emphasized the importance of bringing more people into the process and identifying companies willing to invest time and energy into the campaign. Already, faculty members have offered to help Swain with refining his amendment, and students from Columbia’s Climate School have reached out with ideas to support the effort.

After he finished reading his proposal, Swain was asked by a member of the media about the chances of this amendment getting ratified. Swain answered, “People tell me that it’s unrealistic, that it’s a pipe dream. But that’s the same thing people said about the idea of an American nation. Yet, after years of struggle, the dream came true, and here we are.”

That belief in America’s capacity to become something greater is not new for Swain. When he was in high school, he spent time in France as an exchange student and often asked the locals: “Why did France give the United States the Statue of Liberty?” The adults he spoke to told him they had seen, in the dream of America, its potential.

That idea stayed with him. Decades later, even as some in France have begun to call for the statue to be taken back, Swain still holds onto the belief that America can live up to that early promise.

“That idea about America—that we have it in us to really do something beautiful, helpful, transformative on behalf of everyone […] I haven’t quite given up on that idea, so I push on[ …] this is a gesture and the direction of the America that I wish to live in.”

Swain via Baron Carr

UN Headquarters via Wikimedia Commons

0 Comments

0 Comments