An archaeology major’s illustrated journal on International Archaeology Day.

Soon after waking up from a nice sleep-in after a stressful midterm week, I joined a team of faculty and students from the Columbia Center for Archaeology on the 9th floor of Schermerhorn Extension on October 18. It was the third Saturday of October. Every year on this Saturday, archaeological organizations around the world celebrate International Archaeology Day by presenting events and programs for people of all ages and interests. Although that maze of a building always feels evil to me, the 9th floor of Schermerhorn Extension has become a place of weekly visit ever since I came to Columbia as an archaeologist-in-training. From there, the team moved tables and boxes of oddities downstairs and across Amsterdam to set up our Archaeology Day presentation and activities at the Gatehouse Garden, welcoming any passerby to come up and learn about the curious world of archaeology for the entire afternoon.

So, what is archaeology? I’ve been getting a lot of practice explaining my own choice of study to people from various backgrounds. The other day, a friendly stranger sat next to me while I was having a croissant for breakfast on a bench in front of Lewisohn Hall. “What do you study?” they asked during our conversation. A few minutes later, I found myself excitedly explaining the Alvarez Hypothesis to answer their follow-up questions. Although, that concerns the study of paleontology—not archaeology. So, no, archaeologists don’t study the extinction event of the dinosaurs. Another common confusion, especially coming from non-native English speakers such as myself, is thinking that we design buildings. Buildings are cool, and I guess archaeologists care about them, too! However, designing them is the expertise of the architects—not archaeologists. In short, archaeology is the study of material remains of the human past. We find really old stuff and use them as evidence to learn about really dead people.

Fueled with excitement to share our love for the study, the archaeologists at Columbia laid out a bunch of eye-grabbing artifacts on our tables along the sidewalk of Amsterdam. One graduate student brought their cat, Eloise—whom I believe to be a leading expert in purr-sian archaeology—to oversee our operation. It didn’t take long before a crowd of curious passerby gathered around us with their questions. Among them, the most inquisitive were the children, who insisted on knowing the chronological and geographical origins of each and every artifact we had—a spirit which represents the study very well. I’ll admit; I didn’t end up being much of a help. Having only taken some intro-level courses and a few months of museum archive–collections experience as an intern, I lack the sufficient knowledge to comfortably explain most aspects of our study just yet. Not to mention, I was the only student there who hadn’t done any fieldwork yet. So in many ways I felt like I was there with the children, eager to learn from the rest of the team, who were much more experienced than me.

After a few hours of tabling, I bid farewell to the kind people from the Columbia Center for Archaeology, and took a train down to the South Street Seaport Museum, where the 40th annual public program presented by PANYC (Professional Archaeologists of New York City) took place. The program was titled Archaeology of the Maritime City: Stories from the Depths. There, professional archaeologists of the City presented fascinating stories about their work.

The first speaker was Dr. Joan H. Geismar, a founding member of PANYC, and an alum of both Barnard College and Columbia University. Dr. Geismar showed the audience a little Dutch brick, the star of the presentation, which she had collected from her very first archaeological project at 175 Water Street in 1982. The little Dutch brick was among the many of its kind used to sink an 18th century ship into the water to create landfill for an entire city block.

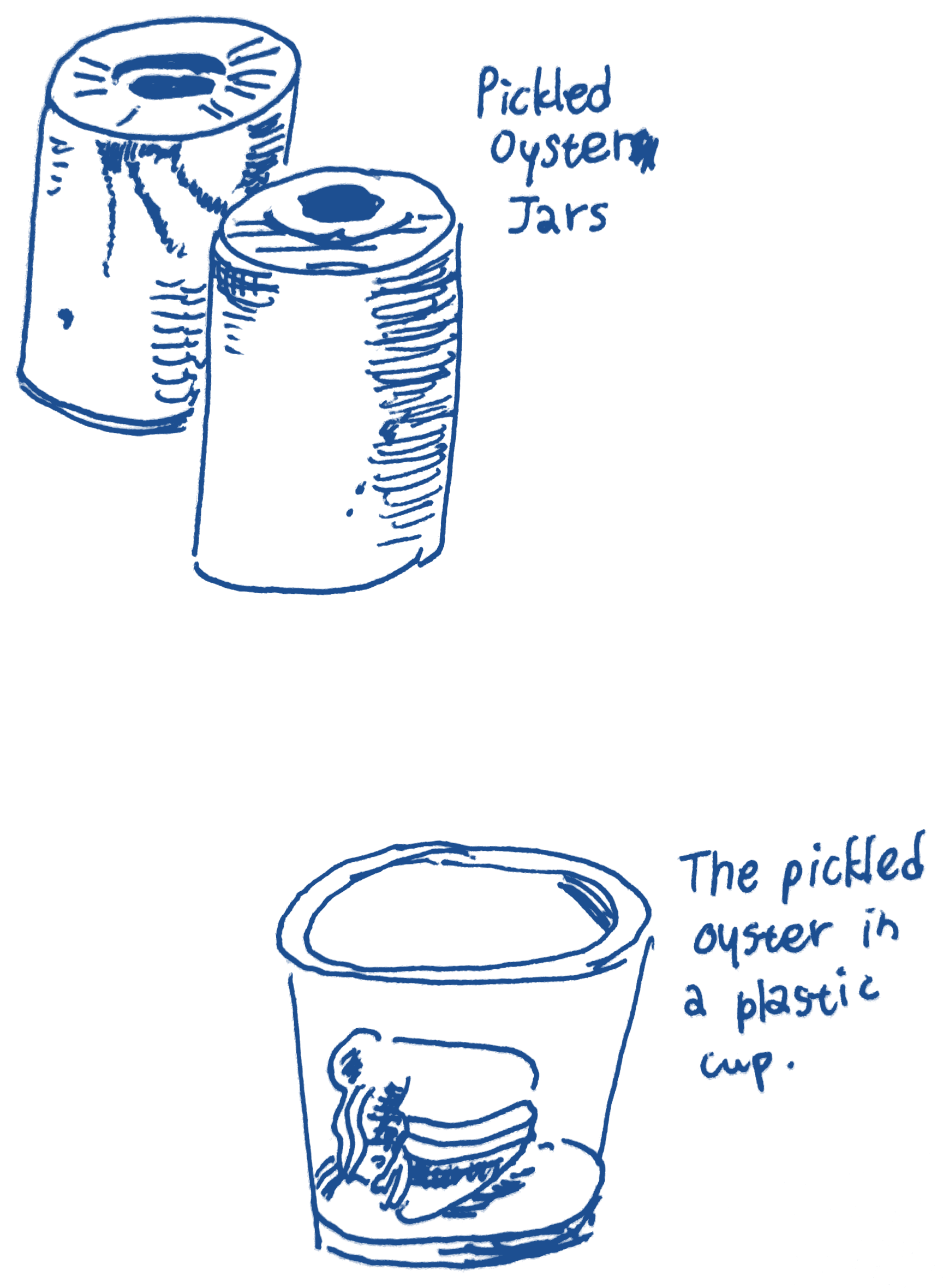

Among the many knowledgeable and enthusiastic speakers, what captivated my attention the most was Chris Pickerell’s presentation on the New York pickled oyster jars. In the presentation, Pickerell explained how these cylindrical jars came to be produced in large numbers in 18th-century New York. Pickled oysters were among the most popular foods for the city’s gentlemen, and the ingenious potters developed a special style of jar, which was easier to make and much more convenient compared to the traditional wooden kegs. By the end of the program, Pickerell revealed a delightful surprise—historically-accurate New York pickled oysters made according to the many 18th-century recipes Pickerell had personally experimented with. I have always been fascinated by the everyday life of people in the past, especially in regards to food and crafts, so Pickerell’s presentation at Archaeology of the Maritime City was, without a doubt, my favorite moment of International Archaeology Day of 2025.

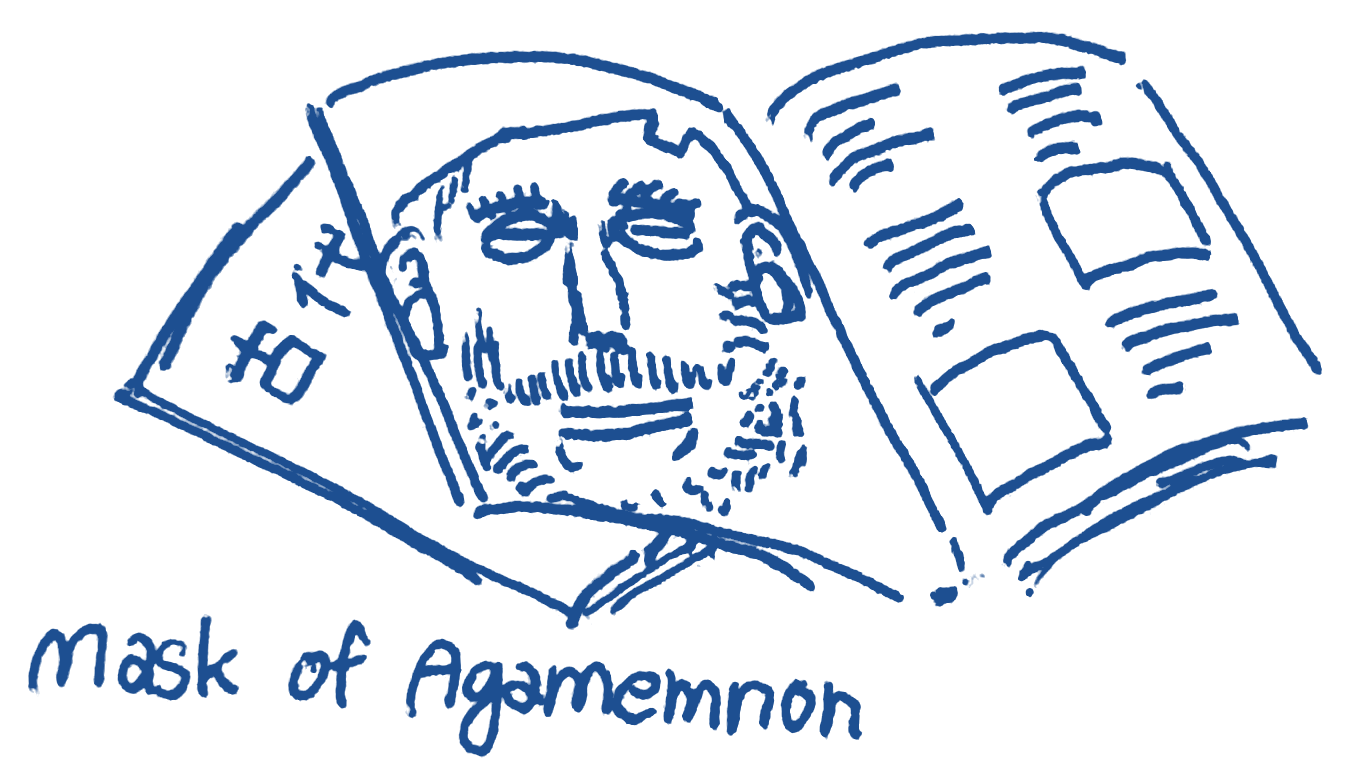

Looking back on a day about not only the celebration of a common interest, but also the passion for sharing and learning, I am reminded of why I love archaeology so, so dearly in my heart. Ever since I saw a picture of the golden Mask of Agamemnon on a page of a Taiwanese weekly magazine titled Illustrated Encyclopedia of Ancient Civilizations as a child, I wanted nothing more than to be among the experts who get to see these artifacts first-hand, and use them to reconstruct the lives of distant past. I look forward to the next International Archaeology Day, and I hope by then and every year onward, I will be able to share more and more with you.

Learn more and sign up for the mailing list on the website of the Columbia Center for Archaeology.

Illustrations via author

0 Comments

0 Comments