Content warning: This post contains descriptions of an assault of a Black student and racial profiling.

On Thursday, April 11 at around 11:30 pm, Columbia College senior Alexander McNab was pinned to the counter of Peet’s Coffee by a group of six Public Safety Officers after failing to produce his ID at the Barnard gates. Video of the event has since gone viral, aided by reports in outlets like the New York Times and NowThis. The response of Barnard’s administration in the days after the event has raised questions about Public Safety’s policies and its role on campus, highlighting a culture of implicit bias in policing at Columbia and Barnard. The six officers involved have been put on paid leave as Barnard opens an investigation into the assault.

McNab’s assault is not an isolated example of racial profiling on Barnard or Columbia’s campuses. Though these are the videos that have captured national attention, they stand as just a few examples of a long-standing pattern of racial bias in policing at this institution, which stands alongside the institution’s deep historical ties to slavery and recent bouts with white supremacy.

Racial Profiling at Barnard and Columbia

At 11:15 pm on Thursday, April 11, McNab got out of dance practice for Ijoya, Columbia’s African dance group, in the Lerner Party Space and saw a Facebook post advertising free food in the Milstein Center left over from a recent event. He crossed 116th Street in front of a Barnard Public Safety van, running to catch the light before it changed, (a fact later used by Public Safety officers on the scene to justify his assault,)

As he entered the Barnard gates, he didn’t show his Columbia University ID to the guard stationed inside the booth. Per Public Safety guidelines, this is required for all students who enter Barnard’s campus after 11 pm, but as many Columbia and Barnard students have noted in the aftermath of McNab’s assault, this rule is selectively enforced. Multiple Black students have told Bwog that they have been ID’d or otherwise racially profiled by Public Safety officers at Columbia and Barnard while white students have not. Bwog interviewed Alexander McNab shortly after the assault, in which he remarked on the reason he refused to show his ID. “I was fed up [with this racialized enforcement], so I kept walking. I didn’t run or anything. I didn’t want to look like I was resisting arrest.” Once he entered Milstein, he approached the counter at Peet’s and began serving himself from the leftovers, chatting with Caroline Cutlip (BC ‘20), who would later film the encounter.

Several Public Safety officers followed McNab into the Milstein Center and continued asking him for his ID, which he refused to produce. He expected the verbal altercation with Public Safety upon refusing to show his ID, and raised his voice to Milstein patrons would be aware of the situation. He connected his intentions to other instances throughout history in which Black activists have broken rules to further awareness of civil rights abuses.

What he did not expect was for the interaction to escalate to physical violence. “They said I was ‘aggressive’,” he said, echoing language Public Safety used immediately after the assault. This itself is a dangerous stereotype; studies have shown that Black men are seen as larger and more threatening than white men of the same size. This may lead to the justification of force used against them. However, McNab pointed out, “I was aggressive with my words, but [the Public Safety Officers] were aggressive with their bodies.”

Daria Forde (BC ‘20), who had been studying on the second floor of Milstein prior to McNab’s assault, approached the officers after seeing the continued argument over whether McNab should be permitted to remain in the building. Public Safety tried to rationalize their actions to bystanders by citing the fact that he had run across Broadway. Forde pointed out the contradiction in their justification (McNab had not actually run into Milstein). Video shows her being told to “relax” by Public Safety officers in the ensuing dialogue.

“I think him telling me to relax was a clear sign of what was going on there,” Forde said. “It was absolutely racial profiling because he racialized me as the angry Black women or the aggressive Black woman even though I was just asking him a simple question.”

Several Black students have spoken with Bwog about racist interactions with Public Safety. McNab himself cited three other occasions when he was stopped by Public Safety prior to his assault. One occurred on Columbia’s campus in Lerner Hall; a student worker thought he had failed to swipe his ID at the second-floor turnstile, and stopped him to confirm his ID. The other two occasions occurred in Barnard Hall after late night dance rehearsals. On one occasion, he was stopped and asked for ID while leaving campus, despite Barnard policy only requiring ID checks for those entering the main gates after 11 pm. The second time, he had gone to the bathroom barefoot in the middle of practice in Barnard Hall. He was stopped and ID’d by officers who admitted that they thought he might be one of the people experiencing homelessness who had been sleeping in the building.

Similarly, Forde said that her friend, a Black Columbia senior, was approached by Public Safety one night while she was sitting on Low Steps. The officer “told her that she wasn’t allowed to sit there at that time of the night” and “continued to question her and ask for her ID.” Unlike Barnard, Columbia does not require anyone to show ID to enter the campus gates after 11 PM and students often sit on Low Steps at night. Forde personally shared that she’s had “weird encounters with people who work at the desk of the dorms,” and expressed a general feeling of discomfort around Public Safety officers.

The Administrative Response

Public Safety, and Barnard administration more generally, have been hesitant to label McNab’s assault racism or racial profiling. The earliest statements released to Bwog and the student body at large did not directly mention the violence McNab experienced or the conduct of Public Safety at all, let alone discuss any of the questions of racial profiling raised in the social media and student news coverage of the incident. The first statement to address the anti-Black violence of the incident was given by Columbia Dean of Multicultural Affairs, Melinda Aquino at 4:40 pm on Thursday, April 12. President Sian Beilock would not release an updated statement acknowledging the anti-Black violence of the incident until Sunday, April 14, almost three days after the assault originally took place and only after significant media coverage.

However, students have emphasized Public Safety’s treatment of students of color, particularly Black students, is at odds with their mission statement, which emphasizes the “paramount importance of maintaining the ‘safety and well being of students, faculty, staff, and guests.’” This schism was evident at the listening session hosted by Barnard administration on Friday, April 13 in the aftermath of McNab’s assault.

McNab, Forde, and Cutlip all critiqued the listening session for failing to answer student questions. McNab, who attended the session and ultimately asked for an apology from the administration, acknowledged that “ they did say that they had done things wrong but I don’t think they fully understand or understood what that meant.” Cutlip, who was also there, said it was “a mess” with “a classic, corporate kind of response” to students asking “hard-hitting questions.”

At the listening session, Public Safety administrators highlighted the “tension between openness and ID checks and access…making sure the campus, as open as we are in New York City, is safe.” Student comments, however, focused far less on the broader question of “safety;” instead, they were concerned with, as one student put it, “whose safety we’re prioritizing” on campus. The tension between these differing priorities led to tensions throughout the listening session.

Throughout the listening session, students of color voiced discomfort with Public Safety’s presence on campus. One student asked whether lessons Black parents teach their children regarding how to interact with police officers should be applicable to interactions with Public Safety. Administrators answered that they hoped students of color would have “a different interaction” than they would with outside police officers since Public Safety is a “slice of the community” but student reaction indicated that is not the case. Public Safety officials at the listening session were asked whether they knew that “there are many students on this campus, specifically students of color, who know and understand that that uniform does not represent safety to them.” Aside from these comments about being part of the community, Public Safety failed to answer student questions about these issues.

One student brought up an incident last year in which a white male student gained access to a Barnard student’s room while intoxicated and urinated on her belongings. Another attendee made a direct comparison to the recent arrest of an African-American college-aged man in Barnard Hall at 7:45 PM, long before the campus shuts down. These comparisons raised a larger question of who gets to be seen as a student on Columbia and Barnard’s campuses. In constantly asking Black students to bring out their IDs and prove that they “are allowed” to be here, Public Safety can undermine any sense of belonging students of color have on campus. At worst, it subjects them to violent policing, of which McNab’s assault is only one example.

At the listening session, students called out administration multiple times for using the euphemistic term “incident” to describe Public Safety’s violence toward McNab. McNab approached administrators at the listening session for an apology, which was given without acknowledging the racial dimensions of the assault. They also described McNab as “angry” despite the fact that he remained calm throughout the interaction at the listening session. One student called the apology “an insult” for failing to address the issues of race that students had pushed administrators to address. Dean Natalie Friedman, Dean of Studies and co-interim Dean of Barnard College, was the only administrator at the listening session to publically call McNab’s assault “a racist incident” in her apology. Beilock did not attend the listening session, though a representative from her office was in attendance.

McNab said that after the incident Roger Mosier, Vice President for Campus Service, approached him privately and said that he agreed that the assault was racist. McNab gave Mosier credit for approaching him and voicing his opinion but felt it reflected that Mosier might “[feel] as if his morals have no place in his position as a university administrator.” He went on to point out that if Barnard was creating a work environment where upper-level administrators had to remove their morals from the duties of their job, “that’s a very dangerous thing.”

Additionally, Public Safety failed to answer even the most concrete student questions raised at the listening session and seemed confused by their own policies. When asked whether Barnard kept track of incidents of bias perpetrated by Public Safety Officers and if those numbers could be reported to students, Mosier didn’t know how those numbers were tracked at the most basic level or if there were Barnard-specific numbers. He was unsure if those numbers would be tracked by Title IX or another office within the university. When reached for clarification, Barnard didn’t give specifics and only stated that“All student complaints are taken seriously and are documented accordingly.”

Student mental health in the aftermath of the assault was also a concern of those attending the listening session. One witness in attendance at the listening session noted that the assault had left her “more scared” on campus, a charge not addressed by any Barnard administrators in attendance. Questions were also raised about what Barnard would do to address the mental health impact both on McNab and Black women on campus. President Beilock has since personally apologized to McNab, but none of the witnesses have reported hearing from Barnard’s administration.

It was also revealed that Public Safety only receives two days of training, twice a year, administered by the head of Public Safety. It was unclear at the listening session what is covered in those four days of annual training and whether it is supplemented by other training throughout the year. When contacted for clarification, Barnard stated: “Public safety officers are college employees who are licensed by the State of New York and are trained, certified and registered pursuant to the New York State Security Guard Act of 1992. Barnard’s training curriculum includes Title IX and other forms of discrimination.” Students pointed out that unpaid peer educators at Well Woman receive more training than Public Safety; administrators indicated that improvements to training would be included in the ongoing investigation.

Student Responses and Alumni Letter

Outside the listening session, students have been vocal about their anger at Barnard’s handling of the case. Several protests took place in the days following the assault. The first took place outside the Barnard gates the same Friday as the listening session before moving into Milstein and Barnard Hall (where Public Safety’s office is located). Forde described it as a “white liberal protest” where “white students didn’t really take it as seriously as it could’ve been taken.”

A smaller protest took place on Sunday, April 14 with both Cutlip and Forde attended. At the end of the event, Black women stood on Low Steps and began sharing their experiences with Public Safety and at a primarily white institution with admitted students and their parents. Forde commented that this protest, though it featured more voices of Black students, “kind of personalized [the assault] and didn’t make it about the actual victim.” She felt that both these protests these actions felt more performative than completely productive, a frequent charge against protests at both Barnard and Columbia.

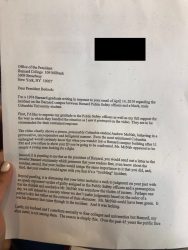

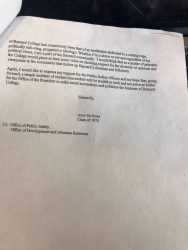

Though McNab said that he’s felt largely supported by the student body of Columbia and Barnard, this support has not been universal. On Monday, April 22, Bwog received reports that Barnard Public Safety was distributing a letter to students in the Diana Center. An officer had a stack of them in the McIntosh Dining Room and handed one to a student. They did not appear to distribute additional copies. In it, a Barnard alumna expressed her“full support” for Public Safety’s violent actions. The letter goes on to refer to Alexander McNab as “Andrew” and express disapproval of Beilock’s April 14th statement acknowledging the racism and racial profiling of the assault. When reached for comment, Barnard reported that they were “currently investigating” the Public Safety officer’s decision to hand out the letter to students. Photos of the complete letter are attached at the bottom of this post and we will update when we receive comments from Barnard.

Within the campus debate over the specific assault, is the question of how to change the racially biased system currently in place which proves difficult to answer. Both McNab and Forde suggested a system like Columbia’s, which requires swipe access to buildings after certain hours. This secures indoor spaces while providing more open access to campus. Forde also emphasized that the Public Safety officers involved need to be fired and administration and faculty need to be open to changing policies for policing on campus or an assault like McNab’s “will absolutely happen again.”

- Page 1 of the letter Public Safety handed out to students in the Diana Center.

- Page 2

This post is the first in a series reporting on incidents of bias perpetrated by Public Safety at Columbia and Barnard. If you would like to share your story please feel free to fill out our secure, anonymous Public Safety Campus Climate Form or email tips@bwog.com.

2 Comments

2 Comments

2 Comments

@Anonymous Not an assault. The student was repeatedly asked to show an ID. He didn’t comply at which point he was legally trespassing. At which point, Public Safety had the right to remove him from campus. When they began that process, he showed them his ID.

@anon Everyone should be mandated to show their ID at all times and this would be a nonissue.