Three scientists call us to action to avoid catastrophe.

As the global temperature continues to rise, Columbia scientists gathered on Wednesday to discuss the future of water in the United States and around the world. Hosted by Alexander Halliday, director of the Earth Institute, the panel brought together three leaders in different fields of climate research and action.

A physician and epidemiologist, professor, and vice-chair of research in the Department of Environmental Health Sciences at the Mailman School of Public Health, Ana Navas-Acien concentrates on the role of the environment in human health. Water contamination affects different communities in different ways, and Navas-Acien’s work focuses primarily on access to clean water for rural and Indigenous communities.

Upmanu Lall, a professor of engineering and Director of the Columbia Water Center, grew up in India, where nearly every aspect of daily life relies on water. All religions, he remarked, have water as part of their ceremonial processes, and everything involving life, whether in the human body or at the planetary scale, is driven by water. Lall has conducted research on four continents, working with governmental bodies as well as farmers and tradespeople, investigating and coming up with solutions for current water problems.

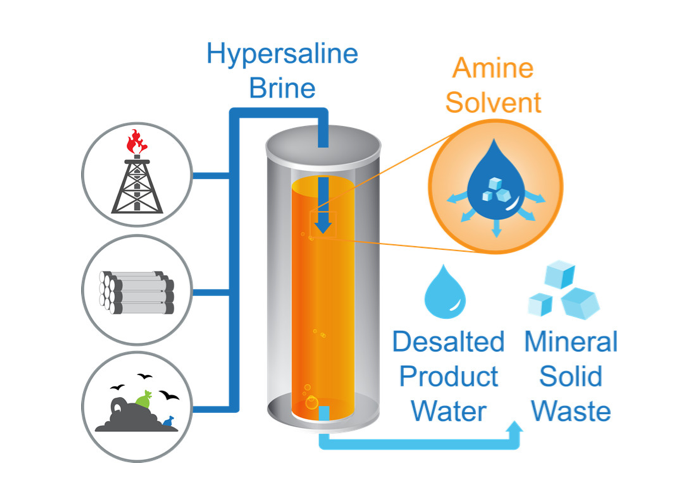

Ngai Yin Yip, a technologist and environmental engineer, recognizes that technology has a large role to play in addressing our water challenges; it brought us to where we are today, and as technology improves, it will continue to play an essential role in solving current problems with water infrastructure and purification systems. Yip’s current research involves physical chemical separations: the process of removing contaminants and impurities from water to make it safe for consumption, or taking out the water molecules and leaving everything else.

There’s no substitute for water on the planet; without it, life wouldn’t exist. In America today, areas across the country are grappling with challenges preventing them from having reliable access to clean water. When Lall worked in developing countries, he was asked if he saw the same issues in the United States, a nation with plenty of resources and the potential to improve the quality of life of its residents. Lall responded by saying that, from a structural perspective, the US is a country in decline; our infrastructure which was state-of-the-art sixty or seventy years ago hasn’t been updated since. The same fundamental problems penetrate the heart of American infrastructure as those that exist everywhere else in the world: mainly, how to balance quality, quantity, and affordability of the country’s water supply.

Recent statistics show that 850 water main pipes break per day in the US, leaving a gap of several days where residents have no access to water during repairs. In the 1950s, the number was almost exactly the same – but per year. The numbers are higher (and the solution slower to achieve) in poorer communities or those populated by minorities, where representative politicians have less power and voice to get the problem solved. The last major flood in Jackson, Mississippi, left 180,000 people without water services for over a month, and the problem is chronic; the city hasn’t been able to pay the necessary price for proper investment in infrastructure, so the short-term solutions fail year after year. As climate change exacerbates natural disasters, floods of the magnitude capable of taking down the city’s water supply will become increasingly common, and short-term solutions won’t be able to cut it. But how do you solve a structural problem with no resources? Many communities lack the financial or technical capacity to lay out what their problem is, much less to be able to solve it for themselves.

This disconnect is where Navas-Acien’s work comes in. As part of a nationwide team effort, she examined data reported to the EPA as part of the Safe Drinking Water Act (of which Tuesday was the 50th anniversary) and found that smaller communities, that are predominantly Native American or Hispanic and Latino, and communities reliant on groundwater are the most heavily affected by contaminants and the most vulnerable to government ignorance. Residents living in these areas have much higher quantities of contaminants in their bodies than the national average. Arsenic, uranium, and other toxic chemicals are getting into the body, under the skin, and worsening existing health issues. Ignored by politicians, and underserved by the government, rural and Indigenous community water systems are almost entirely reliant on the private sector, but most residents accept its help without any information. Navas-Acien’s team pushes to change the way we conduct research by bringing in direct community participation and making sure that the technology is comprehensive and effective locally. With climate change’s disproportionate effects on Indigenous communities, particularly in the Great Plains and the American Southwest, local knowledge and direct interactions with scientists and engineers can dissolve the communication barrier between scientists, engineers, and the public. When communities embrace and contribute to the development of solutions, they learn how to advocate effectively for themselves and push harder to create change.

For Yip, the most urgent investment the US can make is in the people; training future scientists and engineers now helps us prepare for the severity of climate change-related challenges. We don’t know if we’ll have five or ten years to come up with solutions, and as technology improves, the human right to clean water and sanitation becomes more important than ever. Yip concentrates on the nexus between water, energy, and the environment, all of which are interdependent and integral to one another. As some problems aren’t treatable with conventional solutions, the need for innovation is particularly pressing. Most of the country’s infrastructure is well over its intended lifespan. We have the opportunity to modernize the technology and plan for the long-term. Improving the country’s infrastructure for the next fifty years and beyond will become increasingly important as more of the old tech starts to fail.

Public technology is radically unprepared for major climate disasters that the world will face in the coming years. Floods, droughts, and aqueous pollution are all sensitive to climate change. We have many large dams providing energy and protection that are well past their design age, and worsening tropical storms and sea level rise pose an imminent threat. For Lall, the scary thing is that it’s flying under the radar; instead of fixing the root of the problem, politicians are encouraging people to leave the affected area. But increased migration just compounds existing infrastructure and water supply issues, and with climate change becoming more extreme, access to modernized technology is going to become very important very quickly. Lall wonders if we can put together the money quickly enough to act in time.

If there’s anything to take away from this panel, it’s that climate change is terrifying. Everything on which we rely for life, down to the very thing that enabled life to exist on Earth, feels the stress of the mounting danger. But leading scientists and researchers have ideas for the present and a plan for the future, and they rely on technology, policy, and people. Yip is developing energy-efficient and sustainable methods for removing contaminants, including hyper-saline brine management, as technological innovation has a central role to play in addressing current and future challenges to our water supply. Lall has an idea to develop a brand new model city that demonstrates how to implement high-quality water services with a net zero energy cost, bringing together state-of-the-art machinery and tools, as well as interaction with the government and private sectors. Navas-Acien concentrates on communicating the problems and solutions on a local level, providing vulnerable communities with the resources they need to embrace, adopt, and contribute to positive change. Together, they’re working towards solutions that protect the human right to water, from the individual level to the global scale. There’s a future in sight where we can achieve that ideal balance of water quality, quantity, and affordability, but we need to act—now.

Columbia Climate School Earth Series event banner via Eventbrite

Flint, MI sign via Flickr

Desalination graphic via Columbia Engineering

Teton Dam Flood image via Wikimedia Commons

0 Comments

0 Comments