On Tuesday, Staff Writer Charlie Bonkowsky attended an expert panel hosted by the Columbia Political Union: Russia and Ukraine: What’s Next?

One month ago, a panel of Columbia professors discussed what Putin had to gain from threatening Ukraine, and whether the buildup of troops on the border was really a prelude to war. On Tuesday, the same professors analyzed Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the situation in both countries, and the international response from the US, NATO, and the EU.

The panel was moderated by the Columbia Political Union, with Peter Clement, a professor in the Salztman Institute of War and Peace Studies; Elise Giuliano, a lecturer in political science and the Director of Graduate Studies of the MA program at the Harriman Institute; Kimberly Marten, a professor of political science at Barnard College; and Thomas Kent, an associate professor at SIPA and former head of Radio Free Europe.

The first conclusion they reached echoed that of a month previous: “Putin,” as Marten said, “is at the center of everything.”

But Putin’s motivations for starting this war are less clear. As he did a month ago, Clement theorized about Putin’s historical reasoning—that, worried about his legacy in Russian history, Putin is seeking to claim a modern-day mantle as the “gatherer of the Russian lands,” and reclaim parts of the Russian Empire. Fundamentally, Clement said, Putin has never believed that Ukraine has a right to exist, and much of what he’s done as president, including the publication of a treatise calling Ukrainians and Russians “one people,” has demonstrated that.

Kent and Marten spoke about Putin himself, and the fact that for all his portrayal as a calculating, confident leader, the invasion of Ukraine has clearly not gone as well for Russian forces as they expected it to. Though he was previously an intelligence agent himself, Marten said, he lacked sound information about what the response to a Russian invasion would be, both from the West and from Ukraine itself. Kent agreed, noting that Putin has “become distant from good advice,” possibly due to fears of COVID-19. Hopefully, he said, Putin seemingly becoming more irrational is simply a tactic to scare the West, that the US and NATO will back down if they believe there’s “a madman in the president’s seat.”

If the cause of the war is Putin, though, its effects are felt by the citizens of both countries. A dynamic evident on the front lines, Giuliano said, is the cultural similarity between Ukrainians and Russians; though the countries are distinctly different, there’s a lot shared between them. She pointed to a viral video of a Ukrainian civilian jokingly (and bravely) offering a stalled Russian tank a tow back to Moscow as an example of shared humor, and noted that many Russian citizens have Ukrainian ancestry—former foreign minister of Russia Andrei Kozyrev called the invasion a “fratricidal war” (братоубийственная война).

But war tends to reinforce boundaries, not similarities, she said—boundaries between nations and national identities, and boundaries between individual citizens through the process of “othering”. Ukraine has attempted to blunt this effect and appeal to Russian citizens: on the first days of the invasion, President Zelensky directly addressed Russians on the basis of their shared humanity.

Russian leaders, and Russian media, have not done the same. The official government position, Kent said, is that Russia “is the aggrieved party and it had no choice but to invade.” Putin has accused the Ukrainian government of being nothing more than an illegitimate fascist cabal propped up by the US government, and claimed the Ukrainian military was committing genocide against Russian-speaking minorities in the Donbas region, a false but usefully nationalistic talking point.

But beyond Russian officials’ vitriolic speeches, Russian media has been largely silent. Kent noted that he’d been tuning into Russian television every night, where almost none of the fighting has been shown, and, if it is, the war is described only as a “special military operation” in Ukraine. Clement agreed, but he thought the situation would soon have to change in Russia with the impact of sanctions. Citizens who’d previously been only distantly aware of the war would soon find “the entire world seems to be caving in on [them]” under the economic measures imposed by the US and NATO.

These are the “strongest sanctions we’ve ever seen,” said Marten, and unexpected in their harshness. Before Putin’s invasion, there was speculation that Europe couldn’t commit to unified action, that Germany and Italy—which import large quantities of natural gas from Russia—might push for lighter sanctions. They didn’t. International action has been swift and far-reaching against Russia’s currency exchange and banking sector, and, she said, the universal condemnation of Putin by Western governments has made it publicly poisonous to be associated with Russia. Private companies like British Petroleum and Shell sold their stakes in Russian gas, and Microsoft helped Ukrainian officials prevent a cyberattack.

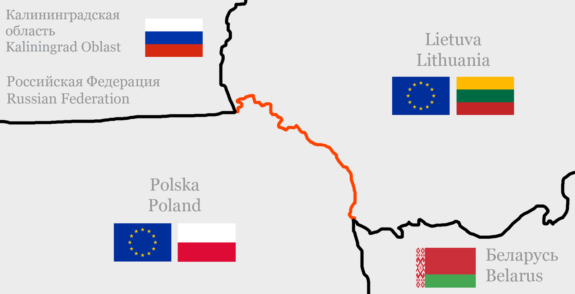

Direct military involvement by NATO, the panel agreed, should be off the table. Starting a war between two powers with nuclear weapons isn’t an outcome anybody wants. However, Marten said, NATO should build up military strength in the Baltic states and Poland, especially to defend the Suwalki gap: the 65-mile connection between the NATO states of Poland and Lithuania, flanked by Russian-aligned Belarus and the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad. If Russia decides to attack the Baltic states, maintaining control of the Suwalki gap would be essential to resupplying the Baltic states. NATO must remain a deterrent, Marten said—the defensive guarantee has to remain a red line which can’t be crossed.

Even if the future doesn’t hold a larger war, the situation within Russia and Ukraine likely won’t improve soon. For Ukrainian civilians, Giuliano said, “it’s a nightmare. I don’t know how to say it in other language,” and spoke about a friend in Kharkiv trying to leave the city as it was under attack. Putin isn’t willing to lose face and back down, Marten said, and the war will likely escalate. Clement agreed—and with so many NATO actors providing aid to Ukraine, he said, the possibility for unintended events rises. As it drags on, he said, the war will “creep up an escalatory ladder.”

The Q&A portion of the event corrected some common misperceptions about the war and Western involvement. Kent told one in-person questioner at the event that, whatever one’s thoughts on US involvement in the Middle East, Western support to Ukraine now is a separate question of “cosmic justice,” which, he said, “is not served by letting Russia murder Ukrainians.”

Marten informed another that the Budapest Agreement, signed in 1994 when Ukraine handed over the nuclear weapons left behind in its territory by the Soviet Union, was not a defense guarantee. Russia, the US, and the UK all agreed not to interfere with Ukraine’s sovereignty—a treaty which Russia broke, not the NATO signatories. “The West is not deserting Ukraine” by not committing troops to the conflict, she said, and it’s important to be accurate in our understanding of the international order both before and after the war broke out.

The panel closed, at least, on a moderately more hopeful note. Having “fundamentally misunderstood Ukraine,” as Giuliano put it, Putin and Russia look significantly weaker than they did a month go, and they continue to face steep obstacles in Ukraine and against the world. As Marten reminded us, “Great powers everywhere make stupid mistakes when they decide to invade foreign countries.”

Ukrainian flag via Wikimedia Commons

Suwalki Gap via Wikimedia Commons

0 Comments

0 Comments