Bwoggers love cool city stuff, so we couldn’t miss out on Columbia’s exhibit on Frank Llyod Wright. Staffers Jack Treanor and Bella Tincher went over this week to ponder buildings, urban decay, and suburban ideals.

In 2012 the entire collected works, papers, and models of the famous American architect was turned over to Columbia and the Museum of Fine Arts. It was decided that Columbia would house the papers in Avery, Fine Art and Architecture Library and the models would be held by MoMA. Now the two institutions are presenting two concurrent exhibitions on the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. While the MoMA exhibit has understandably received far more attention, it would be a shame to not give ample attention to Columbia’s Exhibit currently on view at the Wallach Art Gallery in it’s beautiful new space in Manhattanville, the Lenfest Center for the Arts.

The exhibit Living in America: Frank Lloyd Wright, Harlem, and Modern Housing takes a unique approach to understanding Wright’s work. It contrasts and interweaves it with the concurrent public housing projects in New York City, focusing mostly on Harlem. Wright’s work and the housing projects present two distinctly different modernist housing movements. Both were new forms of housing never before seen, focusing on efficiency, form, and functionality. Despite vastly different contexts and missions these two forms of architecture share a particular time in architecture and are linked through motivations and perspectives. While an untraditional comparison it results in an incredibly rich and interesting exhibit. Visitors are privileged with an incredible wealth of information about both Wright’s work and that of the housing projects. The exhibit does a great job painting a full picture of each of the two focal points. Visitors should be able to leave with a fleshed out picture of Wright’s work and the development of public housing in New York and when viewed together they produce a rich understanding of the nature of housing in the mid-twentieth century.

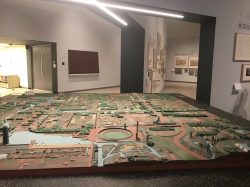

Through the exhibited works of Wright we can see Wright’s vision of America. It is simultaneously modern and pastoral. The centerpiece of the exhibit his Broadacre City development concept. The massive model greets you as you enter the exhibit. From a distance you can start to grasp the particular flavor of Wright urbanism. Sprawling and green the model seems to be mix between farm and city. It was Wright’s attempt to refine the suburban and provide an alternative for the dense over packed cities of the time.

Wright’s design arose from a particular modernist sect of anxiety regarding the city. He hated the density, congestions, and seeming randomness of the city. In rejection he envisioned a modern Jeffersonian America in which each family owned an acre and a home. The exhibition presents seemingly endless variations on Wright’s suburban ideal. He strived to make his vision cheap and accessible. Many endeavours were quite novel including pre-fabricated housing and communal ownership.

The exhibition excellently emphasizes the ways in which Wright’s anxiety about urban decay reflected in the large-scale public housing projects. Slum-clearance, the often racially motivated movement to demolish old tenement housing and build new large modern buildings, arose from essentially the same fears regarding density and congestion that motivated Wright. Everyone should strive to gain greater understanding of the public housing in New York City. About half a million people live in public housing across the five boroughs and this exhibit does a great job of tracking the development of these projects from when they were a novel to when they started to receive backlash and taper off.

The exhibit raised many very interesting questions regarding the history of American housing. To what degree has housing development been inclusive vs. exclusive. While Wright worked to provide his vision of the ideal American life cheaply and plentifully he ultimately failed. The effectivity of public housing is also brought into questions in regards to both creating vibrant urban fabrics and acting as a means of social engineering.

The exhibition relies heavily on architectural examples. As you explore the gallery space you are presented with panels devoted to a single project. The projects consist of either Wrights work or a large scale New York housing project, usually public housing. The wealth of blueprints, sections, and photographs were truly impressive. The information about each building is incredibly detailed. In this sense and others, the exhibition seems to cater to those that have a significant architecture background. It gave little to help contextualize the time and places the exhibit focused on. Because of this the gallery takes a long time to unpack. Many of the overarching themes that connected the primarily sub-urban works of Frank Lloyd Wright and the dense public housing developments were left to the audience’s discretion.

Despite the erudite nature of the exhibit it is undoubtably a can’t miss. The visuals themselves make it worth it and the information regarding post-war housing developments help contextualize many of the decisions made in urban design during this time.

- Bwog writer and architecture student Bella Tincher enjoys the exhibit.

- Wright’s large Broadacre model commands your attention

- Details of the model

- Examples of architectural cases

- Bella appreciates the mediocre space planning of the Lenfest Plaza

- Bella attempts to decipher the Broadacre model

1 Comments

1 Comments

1 Comment

@Anonymous Great article.