In a seminar hosted by the CSC, artist and technologist Jan Nikolai Nelles discusses the colonialism of cultural heritage as ownership transforms digitally.

Jan Nikolai Nelles, a multidisciplinary media artist based in Berlin, undertook a “hacking” project in 2015 along with fellow artist Nora Al-Badri. This mission entailed scanning the statue of Nefertiti in Neues Museum, Berlin, and publishing the data to the public.

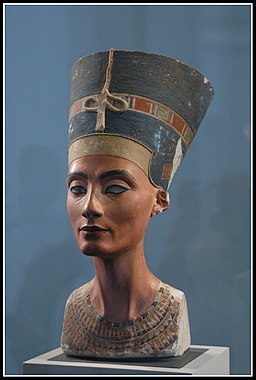

Made of limestone and stucco, the Nefertiti bust is a statue of the Egyptian queen, discovered in 1912 by German archaeologists during the region’s colonization. Ever since the statue’s excavation, European powers have downplayed the discovery’s significance to Egyptian authorities, and European archaeologists refused to provide professional training for excavation to local Egyptians. Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA)’s two failed requests, in 2009 and 2011, for the return of the bust of Nefertiti also exemplify colonial control over native heritage.

“These stolen artifacts – most [of them] coming from the Global South – are kept in the Global North,” Nelles stated during his seminar, Technoheritage and the Politics of Digital Preservation. Barnard Computational Science Center held the event on Wednesday as part of the Arts and Computing in NYC course offered between Barnard and the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT).

Nelles realized the crucial role technology played in “facilitating the gray area between communication and mobilization” during Cairo’s revolutionary movements in 2016. He noticed that the Neues Museum, which houses the Nefertiti bust, had made extensive 3D scans of the artifact with no intention to make the data publicly available. He began to conduct a plan of action to make museums a truly public space rather than a secluded academia-facing platform.

So how was Nelles able to make the Nefertiti bust public? The process was surprisingly straightforward: Nelles staged an “Oceans-11-like” secret scanning of the artifact by capturing its data from a portable scanner, Kinet. After releasing the information online, he expanded the bust’s digital accessibility through downloads and collaborative printing with “Chaos Computer Congress 32C3″ in Germany. Later, Nelles’s 3D printed Nefertiti bust was exhibited in Cairo, symbolizing the return of a stolen cultural heritage to its homeland.

Nelles continued his story by describing the dilemmas he faced as an artist. For example, he grappled with the nature of digitized numbers in 3D printing. His technique hinged on plotting specific digits to physically resemble the bust. He begins to question the validity of digital representation: what happens in between those digits? What is missing there, and do the gaps matter in the cultural significance of the artifact? Meanwhile, he also questions whether physical restorations of an original artifact can truly capture the essence of the past. “What is real after layers and layers of restoration? What is left of the artifact itself?” he asked the audience.

Nelles also questioned his role as an artist, rather than a scientist, in technoheritage. He compares the direct copying method used in 3D printing with techniques of photography. While in photography, there is ample room for creativity such as the angle, depth of field, and lines used by the artist, 3D printing is an extremely disciplined science. Nelles evaluates his role as an artist as he participates in the 3D printing process and the validity of duplicating intellectual property. It complicates the relationship between the original and the copy, raising the question of whether they should even resemble each other.

As the seminar came to an end, Nelles moved into a metaphysical discussion of digital technology. He identified 2D as a shadow of 3D, and thus 3D printing as a shadow of a 4D world, with Time as an added dimension. Nelles eventually pinpointed the goal of his project: to retain the memory of a heritage that transcends time. The artist concluded that neither digital nor physical means guarantee a legacy of cultural memory. The effort to preserve cultural heritage largely relies on the circulation of public knowledge through expanded access to learning platforms.

What struck me about Nelles’ work is that after the 3D-printed Nefertiti was “returned” to Egypt for exhibition, he buried the artwork in the Saharan desert. Instead of transferring the item from state to state entities, Nelles exited the cycle of paternal management of the past, returning the object to its rightful source of discovery: the burial ground. This action appears as the artist’s stylish intent to defy the long-standing tradition of privatized authorship of the past to encompass ownership of cultural heritage. By burying the digitized Nefertiti, its cultural significance can be reborn – as it settles into the ground, the world may re-excavate its meanings as a collective this time.

“It’s not about you,” Nelles stated, addressing Western colonial powers, state organizations, museums, and individuals. Through his work on digital public accessibility of cultural artifacts, Nelles advocates for encompassing ownership of knowledge and the past.

“The Nefertiti Bust” via Wikimedia

0 Comments

0 Comments