David Freedberg’s Iconoclasm, published in 2021, is the result of five decades of foundational study on the topic. On Friday, January 28, Deputy Events Editor Ava Slocum attended the Society of Fellows and the Heyman Center for the Humanities’s discussion of Freedberg’s newest work.

Iconoclasm, the willful destruction of images, brings to mind religious and artistic oppression of centuries past through the defacement of statues and idols. But where is this form of censorship present in our world today, and what role does iconoclasm play in current social and political movements?

Professor David Freedberg has been studying these questions for the last fifty years. His book The Power of Images, published in 1991, was formative to many modern studies of iconoclasm in the past and present, from the Near and Middle East to the contemporary United States.The newly published Iconoclasm–the focus of Friday’s Zoom discussion, as part of the Society of Fellows’s “Celebrating Recent Work” series–is a collection of Freedberg’s previous writings on the subject of image destruction through a religious, political, and military lens. The Zoom conversation, moderated by Columbia Art History professor Barry Bergdoll, also featured the insights of panelists Zainab Bahrani, Finbarr Barry Flood, and Andrea Pinotti.

Freedberg, who was born and raised in South Africa, explained that he first came across image-destruction as a form of censorship through studying the written works of Ovid, many of whose sexual or otherwise suggestive turns of phrase were defaced by later censors in early Latin manuscripts. “While art historians [in the past] were so interested in survival,” Freedberg wondered, “so much of survival depends on destruction and what escapes it. How could it be that the survival of the classics was not also seen to be a question of destruction?”

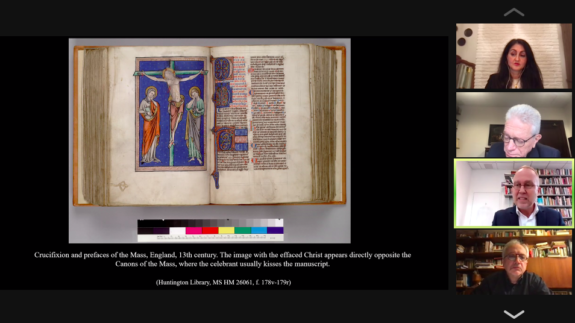

In his reflection on Freedberg’s latest book, NYU professor Finbarr Barry Flood suggested that “there are as many reasons for deliberately defacing images as there are images. These reasons extend beyond the religious conservatism usually attributed as a cause of this defacement.” Clergy in the Middle Ages, for example, unwittingly damaged their incredibly beautiful and rare illuminated-manuscript Bibles by ceremoniously kissing the image of Christ on the cross (although Flood acknowledged that this act, as well as the equally common scratching-out of illustrated demons’ faces, came from political displays of “performative piety” just as often as it was a product of genuine religious devotion).

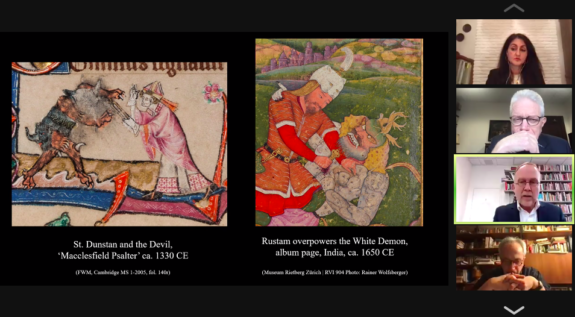

Much of Freedberg’s focus, however, is not on inadvertent damage to religious images, but rather the politically-motivated destruction of works important to a particular culture. He cited the example of Islamic aniconism and historical image destruction in the Muslim world, but was quick to point out, “One of my aims in everything I’ve done has been to argue against the idea that what have been considered ‘barbaric’ behaviors in other [non-Western] people have also happened frequently throughout the Western world.” Finbarr, likewise, said that Freedberg’s book suggests that “iconoclasts treat images as living beings,” but claims that the book “avoids describing this phenomenon as a confusion between image and prototype, which has been racialized in historical condemnations [of the act of destroying religious images].”

Destruction of images in history wasn’t always religiously motivated, however. Freedberg referenced ancient accounts of Syrian soldiers in battle treating images of their enemies’ gods with respect, but destroying art depicting the enemy rulers as a political statement.

Besides its associations with censorship, the destruction and replacement of images connoting oppression can be an affirming experience… provided that it is the people most directly affected who decide how such images should be replaced. Dr. Zainab Bahrani, professor of Ancient Near Eastern Art and Archaeology at Columbia University, brought the conversation from ancient history to the present with her discussion of the removals of statues of Saddam Hussein in her native Baghdad. She described how, for many people, it was a relief to see these statues taken away, since “Iraq was cluttered with so many public statues of Saddam, which felt like a constant reminder of the all-seeing surveillance state that was Iraq under the dictatorship in 2004.”

However, with an influx of foreign journalists and United States military in Iraq at the time, she noted that this mass statue-removal was also poised as an opportunity for U.S.-centric media coverage. The repurposing of the statues took place without consulting the Iraqi people; in one case, a Hussein statue was melted down into bronze which was then recast into a statue of a U.S. Marine. This was an “inadvertent sign,” Bahrani said, “not of the heroic U.S. veteran it aimed to represent, but of the violence that the people of Iraq have endured first at the hands of the brutal dictator, then at the hands of the brutal U.S. war and occupation and its consequences.”

In the discussion about the removal of statues, I was surprised that the panelists did not spend more time on the recent shift in the United States toward removing statues of confederate leaders, slave owners, and racist public figures, especially the removal of many statues in the South after George Floyd’s 2020 murder. Freedberg, at the beginning, briefly referenced the American Museum of Natural History’s removal of their Theodore Roosevelt monument last week, but the vast majority of the conversation focused on iconoclasm in its suppressive and prohibitive contexts rather than as a means for positive growth or social change.

Panelist Dr. Andrea Pinotti, professor at the University of Milan, did reference the role of image-removal in the 21st century with his reflection that in our largely digital modern world, we can no longer completely get rid of images that have already been captured virtually. In the digital age, documentation of images that have been removed or destroyed might serve as a reminder of what is offensive about them and why they have been taken down; the inability to erase all traces of a problematic statue does not mean that its removal is not important.

Dr. Bahrani commented, “There are so many examples of taking down statues in the U.S. and Europe now that some have been speaking of a new age of iconoclasm, one based in political statement rather than religious concerns.” Freedberg’s analysis, anthologized in his most recent book, speaks to the historic roots of these modern movements in harnessing images’ representative power and reflecting on their meaning in today’s world.

David Freedberg’s Iconoclasm is available for purchase from the University of Chicago Press. (The panelists shared the promo code PRICONCU20, which you can use for 20% off through the end of February!) More information on the Zoom discussion and panelists is available on the Society of Fellows and Heyman Center for the Humanities website.

All images (including event poster) via Zoom event screenshots

0 Comments

0 Comments