On Wednesday, January 19, Deputy Events Editor Ava Slocum attended the Institute for the Study of Sexuality and Gender’s discussion of The Inheritance, the 2021 graphic novel memoir by Professor Elizabeth Povinelli.

The places where we live shape our stories and our lives. But, in turn, how much do we shape those places? This question lies at the heart of Elizabeth Povinelli’s work and has special meaning in her new book The Inheritance, which depicts events from her life.

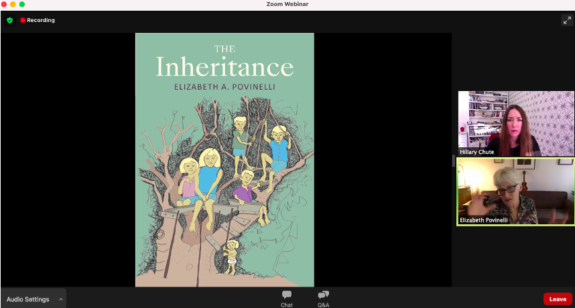

Wednesday’s Zoom session, Heritability and the Ancestral Present: Still and Moving Images, was co-presented by Columbia University’s Department of Anthropology and the Heyman Center for the Humanities. The webinar featured Povinelli in conversation with Dr. Hillary Chute, Northeastern University professor and a leading scholar on comics and graphic novels, who centered the discussion not only on Povinelli’s inspirations for her memoir but also on how the graphic novel format serves to visualize and amplify her memories.

Povinelli is the Franz Boas Professor of Anthropology and Gender Studies at Columbia and a scholar of late liberalism, Indigeneity, and sexuality–in her words, “an anthropology of the otherwise.” Although she has written numerous books on critical theory, The Inheritance represents Povinelli’s first foray into the autobiographical. After an introduction by Columbia Gender Studies professor Jack Halberstam, Povinelli kicked off the discussion with a brief summary. The Inheritance starts with “Little Elizabeth,” Povinelli’s fictionalized younger self, learning in early childhood about her family’s origins in an alpine Italian village and her grandparents’ move from “the old country” to Louisiana. The memoir, Povinelli said, “charts the multiple and often incoherent traces of the past and present,” from her family’s ancestral history to her own childhood in the rural Louisiana of the 1960s and 70s.

Chute pointed out the similarities between The Inheritance and Povinelli’s previous book Between Gaia and Ground, which uses illustrations alongside its analysis of colonial violence, Indigenous dispossession, and our current environmental crisis. Although The Inheritance tells its story mostly through drawings, both works center around the personal impact we have on land and culture where we live. Povinelli implied that, during her early years, she developed a rocky relationship with her family, due in part to her increasing awareness of her sexual orientation. The woods close to her house served as a “safe space” for her. However, in her memoir she acknowledges that the safe space of the outdoors “was made possible on the basis of the disenfranchisement, enslavement, and disempowerment of Black Americans and Native Americans.” She recalled harrowing instances of white colonialism’s legacy in the landscape of her childhood, from seeing Black families pushed out of increasingly white neighborhoods to hearing her parents’ and grandparents’ wary recollections of the KKK. Povinelli recalls these experiences throughout The Inheritance’s pages, with the beginning’s simple illustrations of her family’s map of Trentino, Italy shifting dramatically to pictures of the “dynamics of white supremacy,” which she draws to be “more vibrant and take up more space on the page.”

Povinelli did every illustration for her graphic memoir herself, which adds to the sense of personal history that the book represents. When asked by Chute why she chose this medium to present her life story, she explained, “I grew up drawing. I’m visual even in my writing; I visualize something and then I try to syntax it. Drawing is an easier way for me to lay out a scene,” adding with a chuckle, “grammar is often not my friend.” Throughout the webinar, Chute and Povinelli shared images from the pages of the book. The cover illustration, an image of Little Elizabeth and her five siblings playing together outdoors, was derived from a Povinelli family photograph. At first glance, it’s a sweet picture of childhood and innocent fun in the sun. But Povinelli, echoing her earlier comments on the dispossession of Indigenous people, maintained that “those kids on that tree are a classic example of what white supremacism is.”

A major theme of the conversation was the idea of reparations, or, as Povinelli said, “When we’re handed this inheritance of violence, what do we do with it?” For Povinelli herself, one answer to this question came from her grandmother, the “Gramma” whom she references throughout The Inheritance, and to whom the book is dedicated. Gramma, a strong influence in Povinelli’s life, told her granddaughter stories from her life in Italy and immigration to the U.S., and provided a source of support and perspective for Povinelli’s own experiences of the clashing of cultures. Povinelli wrapped up the discussion with a meditation on the legacies we carry of our heritage and ancestry, stating, “Inheritance doesn’t come from the past. It is the place we are given in the present, in a world structured to care for some and not for others.” Her grandmother, she said, “offered me an insight into this idea;” however, it took a lifetime of experiences to teach her how best to represent it.

The Inheritance, published early in 2021, is no longer Povinelli’s most recent book, but she discussed it with freshness and enthusiasm as if it had been published yesterday. I had not read The Inheritance before this event, and I found parts of the conversation difficult to follow. The summary at the beginning was more about the memoir’s stylistic choices than an actual review of the events Povinelli depicts, but I think the talk was probably geared toward people who had already read the book or who had more background and knowledge of Povinelli’s work.

To me, Povinelli’s analysis of the ethics behind our inheritance of land was as thought-provoking as it was troubling. I grew up in Southern California, a part of this country not only dispossessed from its Indigenous people but also a region that used to be part of Mexico. Povinelli’s description of her native Louisiana–and the ways in which it wasn’t “native” to her and her family–was fascinating for the questions it raised about how we talk about our place in a land where others have been driven out. Late in the discussion, Povinelli remarked that we must consider “the history of literature with relation to” our history of colonization, and how authors and artists before her have contemplated place and origin for the past few centuries. Change occurs when conversations start, and Povinelli’s book may just be a step in the right direction.

More information about the Zoom discussion can be found on Columbia’s events website. The Inheritance by Elizabeth A. Povinelli is available for purchase from Duke University Press.

The Inheritance images via Zoom event screenshots

0 Comments

0 Comments