While graphic novels are often viewed in popular culture as a juvenile form of media, the discussion panel Violence, Politics, and the Graphic Novel highlights the extraordinary power they have for communicating complex and uncomfortable realities to a wider audience.

What comes to mind when you hear the term comic book? Caped crusaders? Crime-fighting man-bats? External red, blue, and whitie-tighties? I’m willing to bet your first thought is not of revolution in Iran or the Lebanese Civil War. Yet comic books– or as they are known in more academic circles, graphic novels– have become a critical literary form for exposing the realities of political turmoil. This panel, hosted by Columbia University French Professor Aubrey Gabel in collaboration with The Maison Française and The Society of Fellows and Heyman Center for the Humanities, included presentations by Dr. Hugo Frey, Dr. Hillary Chute, Dr. Mark McKinney, and Dr. Eszter Szép. Their combined expertise, from visual art to graphic design to history to francophone studies, shows the diversity and multidisciplinary importance of this under-recognized form of art and activism.

There was perhaps no one more fitting to provide the opening presentation than Dr. Hugo Frey. Dr. Frey, a historian of culture and politics, is the co-author of The Graphic Novel: An Introduction. In introducing his audience to the graphic novel, he focused on what makes the form so conducive to political and historical storytelling: visual art. Unlike traditional literature, graphic novels tell their stories through a series of images arranged in a grid on the page. The grid itself forces the reader to imagine the historical narrative as a series of particular moments that caused one another, not as a singular event that occurred all at once. This combats the tendency modern readers have to imagine historical events as inevitable occurrences forced to happen by inescapably massive forces beyond anyone’s control. A graphic novel is made of singular comics. Each comic is a moment. And each moment matters. It is these moments that make history.

The images themselves are also unique to the graphic novel format. Often, authors will model their drawings off of real photographs taken of historical events. This can lead to the accusation that graphic novels are simply an excuse to indulge in sensationalistic depictions of violence for violence’s sake. The appropriation of photographs of real atrocities into stylized graphics is a complicated issue. But does the reproduction of violent images imply the romanticization of violence?

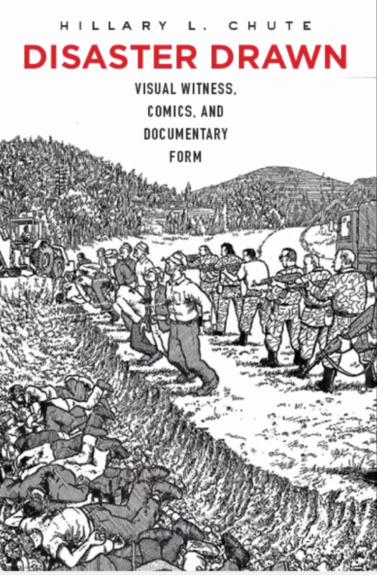

The panel’s second speaker, Dr. Hillary Chute, tackled this question head-on. She is no stranger to this tension between good-faith reproduction and the promotion of violence. Noting how she encountered this in her own professional life as a scholar of graphic novels, she recounted a conversation she had with her publisher about the cover of her book Disaster Drawn: Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form. The cover is a drawing that depicts a group of political prisoners tied up in a line, waiting to be shot. In front of them is a row of the bodies of those who received the same fate. It is uncomfortable. It is graphic. Perhaps worst of all, it depicts the true lives of countless human beings in reality. As Dr. Chute recalled, she asked that her publisher change the image for something less explicit because she was worried it might commodify real victims of violence to sell her book. But the response she received convinced her otherwise: “Well it happened, didn’t it?”

Dr. Chute used this anecdote to illustrate what she views as the value of graphic novels as accounts of violence. In her words, “Graphic form takes something shocking and makes it real.” By removing the jarring realism of the subject present in photography while preserving the factuality of the event being portrayed, graphic form can actually make an atrocity more real, not less.

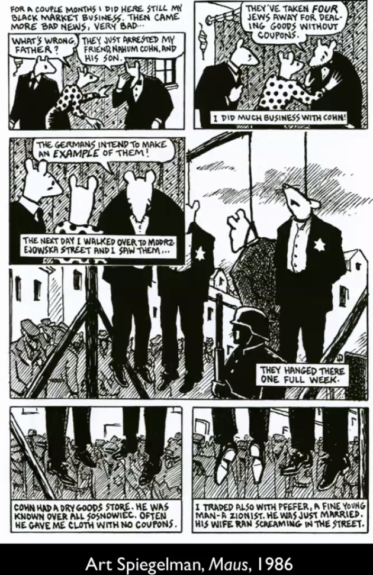

This is not the only manner in which the graphic novel’s flexibility through unreality allows it to get at deeper truths than is possible with traditional journalism. A staple of the form is playing with chronology. While it is intuitive to believe that history should be told as it occurs– that is, linearly– graphic novels often place past and present events next to one another. In many cases, this framing allows the reader to feel the lingering effects of past events on present life. In Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize winning graphic novel Maus, the autobiographical story of his father’s harrowing survival of the Holocaust as a Polish Jew, the tale is deliberately framed as a present-day retelling of the events of the 1930s and 1940s from father to son. By drawing frames of modern American life next to the horrors of Nazi rule, it is impossible to ignore the myriad ways in which all of the characters still carry that trauma with them. The non-linearity of time keeps history alive.

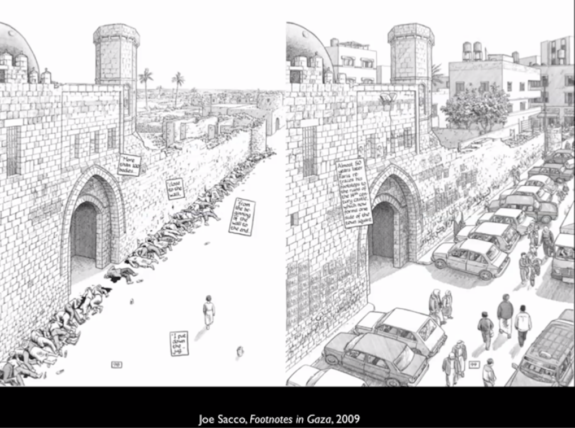

Conversely, the same technique can be used to show how easily history can be forgotten, at least by those privileged enough to move on. This is exactly what contemporary comic-journalist Joe Sacco achieves in his 2009 work Footnotes in Gaza. In it, Sacco places two images next to one another. The first is a rendition of the 1956 Khan Yunis massacre in which 275 Palestinians were killed by Israeli soldiers, their corpses piled outside of the city walls. The second is a drawing of that same city wall a half-century later. The ground where innocent bodies once lay is now a parking lot filled with Israeli automobiles.

Sacco’s graphic reportage may seek to tell the stories of those forgotten by history, but the beauty of the graphic novel today is that it puts that power directly in the hands of the disenfranchised. They can now author their own histories that would otherwise be forgotten to history. Graphic novels are now one of the best ways for first-hand accounts of political turmoil and violence to be recounted. One famous example of this, Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi, depicts the author’s own childhood during the Islamic Revolution in Iran and subsequent young adulthood spent living abroad. As Dr. Ezster Szép explained during the last presentation of the program, Persepolis marks a shift toward telling history from the perspective of the individual.

This trend of individual history-making through the graphic form is stronger today than ever. Working as a professor at Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design in Budapest, Hungary, Dr. Szép has seen the power of the graphic form first hand. Especially surrounding the political protests in Lebanon which culminated in the 17 October Revolution in 2019, Dr. Szép noted many protesters drawing comics to spread the word about isolated happenings. Comics are easily shared via social media because they center easy to understand visuals bolstered by simple written phrases. This makes them easy to translate across languages and cultures. They can also be created quickly and can be shared without involving a secondary publishing agency. Due to these low barriers for entry, many protesters used comic journalism to make sure their voices were heard.

Perhaps the best indicator of the growing popularity and legitimacy of graphic novels is the widespread turnout for this event. The online format of the event––available both via private Zoom link and Facebook livestream––meant that interested viewers from around the world joined in the discussion. Questions were asked not only by students across the United States, but also by those studying in France, Greece, and Israel. Those in attendance were aspiring and current graphic novelists, political activists, or just plain enthusiasts. All united by the unlikely art form of the graphic novel.

If you would like to view the discussion for yourself, a recording of the event will be posted on the Maison Française’s YouTube channel.

Moral Compass by Rana Tawil via Dr. Ezster Szép

Disaster Drawn Cover via Dr. Hillary Chute

Execution from Maus via Dr. Hillary Chute

Khan Unis from Footnotes in Gaza via Dr. Hillary Chute

1 Comments

1 Comments

1 Comment

@Alum In my day graphic novels were novels with a lot of sex. These were called comic books.