Last Tuesday, the Columbia Climate School hosted Dr. Alex de Sherbinin, Dr. Kristina G. Douglass, and Dr. Radley Horton for a conversation moderated by Jeffrey Schlegelmilch on climate change, climate disasters, and how to move forward.

Following a summer characterized by numerous climate disasters across the globe, the Columbia Climate School hosted a conversation on Tuesday evening about climate change and its societal impacts. As the first event of this academic year’s “Earth Series” program, the talk gathered a panel of three professors from Columbia Climate School to discuss their distinct work on climate change and disaster in the past, present, and future.

After instilling a tone of urgency by summarizing recent climate disasters in the US, moderator Jeffrey Schlegelmilch shifted the discussion over to Dr. Radley Horton, a professor at Columbia Climate School whose research focuses on climate extremes, impacts, and adaptation. Dr. Horton situated the conversation on climate change in the present and future by introducing three dimensions of thought about climate change projections. He presented these dimensions as “waves” of climate change, and each depicts climate change with varying degrees of certainty and optimism.

Dr. Horton’s first wave portrays climate change as orderly and predictable. This wave assumes that current climate models are able to create accurate simulations of climate-related activity, such as the effects of greenhouse gasses on air temperature, the extremity of climate disasters, and the societal impacts of extreme climates. Dr. Horton argued that organizations such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which assesses climate change’s risks and considers potential solutions, as well as many private sector entities adopt this narrative. This line of thought presents a hopeful outlook on our response to climate change, choosing to believe that our current knowledge and models of climate are enough to combat the increasing climate disasters.

However, Dr. Horton’s second wave of climate change is “much harder to quantify.” This wave recognizes the complex feedback loops and irreversible impacts we’ve made on the planet, which make the frequency and effects of extreme climate events more difficult to predict. The second wave forces communities to consider not only how climate disasters may affect their own ways of life but also how a disaster in their region will impact other areas of the world, now and in the future. However, scientists and communities who adopt Dr. Horton’s second wave must also acknowledge current climate models’ inability to predict with absolute certainty the widespread effects of climate disasters, adding an unsettling undertone to the state of climate change and modeling.

In light of this modeling uncertainty, Dr. Horton asked the audience to imagine turning around and seeing a third wave that can overpower this unpredictability in climate change by enacting solutions. However, this wave of optimism requires more than just rapid application of solutions; it also demands the use of innovative technology and societal empowerment in order to combat climate change.

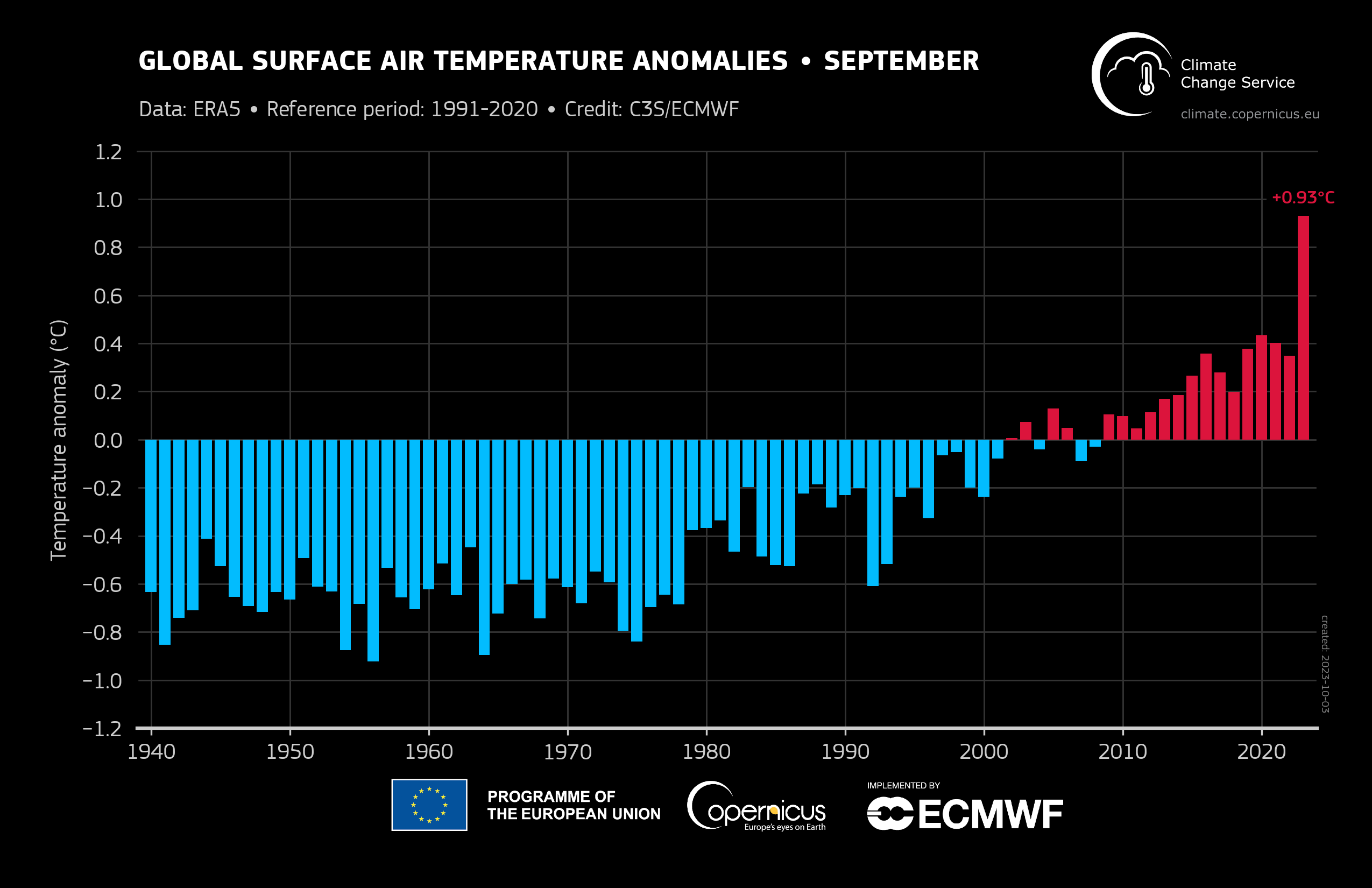

To apply this metaphor, Dr. Horton examined a graph of the surface air temperatures measured from 1940 to 2023. From around 2000, air temperatures have been warmer than usual yet differ from the air temperature average by approximately equal amounts of degrees Celsius, with the only exception being the year 2023.

While this reading poses the challenge of above-average air temperatures and their impacts, Dr. Horton suggested that this “linear reading” of air temperature as primarily steady after 2000 may not accurately depict the severity of climate change. Instead, much research at the Columbia Climate School asks about the key processes, such as rising upper ocean temperatures, missing from models like this. These key processes often reveal further cause for concern by hinting at the more extreme climate impacts we’ve now witnessed, such as the recent flooding in New York City or the wildfires in Maui.

Next, Dr. Kristina Douglass, an archaeologist and associate professor at the Columbia Climate School, transported the audience to the past with her work on people’s interactions with climate and the environment over the last several thousand years. Specifically, Dr. Douglass often works with communities in Southwest Madagascar, a region that contains many plants and animals that are not found anywhere else on the planet. People living in Southwest Madagascar have had to adapt with high levels of climate variability for several thousands of years, which is particularly difficult given that their lives rely on food sources that are unique to their region. However, Dr. Douglass argued that their stories of coping with climate variability may teach us a thing or two about how to respond to climate change. “We can’t forget to think about people,” she said, “and how these climate impacts are affecting people on the ground.”

Dr. Douglass’s work of using archeology to understand past climate change and people’s reactions invokes the power of storytelling as a response to the current climate crisis. By uncovering knowledge about how communities in the past have dealt with extreme climate events, we can draw lessons from history about how best to respond to current climate disasters, despite these events being far more intensive than in the past.

Finally, Dr. Alex de Sherbinin shifted the night’s conversation to the future of climate disasters with a focus on the loss and community displacement that result from climate change. Discussing a recent article authored by Dr. Horton and himself, Dr. de Sherbinin questioned how well certain types of climate modeling can help people adapt to climate change. He argued that while these models may be of some aid, Dr. Douglass’s emphasis on community-centered action is truly needed in order to engage communities in local solutions for climate adaptation.

Additionally, Dr. de Sherbinin refuted the notion that climate migration will only impact those in low-income countries. Using ongoing research at the Columbia Climate School, he demonstrated that people are currently migrating for reasons other than environmental damages, such as economics, jobs, and violence, that are not unique to low-income countries. Even in the US, migration may increase due to lack of reliable water supplies, highlighting the need to frame migration as a global issue.

After their individual presentations, the panelists and moderator fielded questions from the audience. One of the most popular and pertinent questions asked about the role of universities in resolving the climate crisis. In her response, Dr. Douglass admitted that science has “historically done a lot of harm,” which has contributed to its recent distrust by many people across the globe. She argued that addressing the lack of public trust is the responsibility of scientists and universities, who must increase transparency about the scientific process.

While the panelists indicated that there’s much work to be done in addressing the climate crisis, they also left room for hope. As Schlegelmilch stated in his opening remarks, climate disasters “are not impossible problems” but difficult ones, and the night’s discussion highlighted the work being done to combat them. Through the intersection of various areas of research, climate studies can hopefully turn the conversation around and invoke Dr. Horton’s third wave of climate change—a world in which solutions from the past are enacted to reduce climate disasters in our present and future.

Air temperature graph via Copernicus

Maui wildfires via Wikimedia Commons

0 Comments

0 Comments