Last Thursday, Deputy Editor Nikita Nambiar attended an event at the National Jazz Museum in Harlem as a part of an event series called Music on the Brain. The event, was organized by Columbia University’s Zuckerman Institute and featured musical artist T.K Blue and evolutionary biologist Wyatt Toure.

On February 29th, Columbia University’s Zuckerman Institute held an event at the National Jazz Museum in Harlem as a part of an event series called Music on the Brain. This “edition” of Music on the Brain was titled “The Mechanisms of Evolution in Music and Nature.” The focus of the night was the interdisciplinary works of Jazz musician T.K Blue and evolutionary biologist Wyatt Toure.

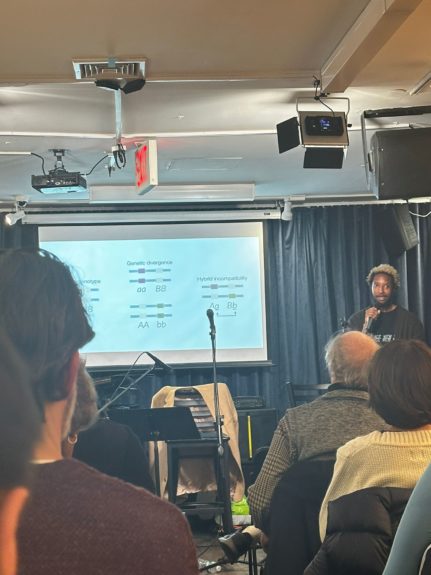

The atmosphere in the venue was charged with anticipation, and a unique energy filled the air. Prior to the artists taking the stage, the venue was alive with animated conversations. Attendees, from a sea of diverse backgrounds, engaged in discussions that flowed like a stream, reflecting the universal language and appeal of jazz. As the audience eagerly awaited the commencement of the performance, the stage became a focal point for the upcoming artistic journey. T.K. Blue, a prominent figure in the jazz world, began setting up for his opening number. This behind-the-scenes moment not only heightened the anticipation but also offered a glimpse into the meticulous preparation and dedication that precedes a live jazz performance.

Amidst the instrument setup, the audience was treated to a brief exploration of the history of the National Jazz Museum in Harlem. The museum’s mission is to inspire knowledge, appreciation, and the celebration of jazz on local, national, and international levels. The museum upholds this commitment through four Core Programs: Education, Jazz &… (Community Engagement & Performance), Exhibits, and Partnerships. Our host spoke of the organization’s programming and dedication to a Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Policy reflecting its commitment to featuring voices and perspectives within the realm of jazz and its adjacent genres. And as he walked over to the makeshift “wings,” the audience lulled and T.K took to the stage.

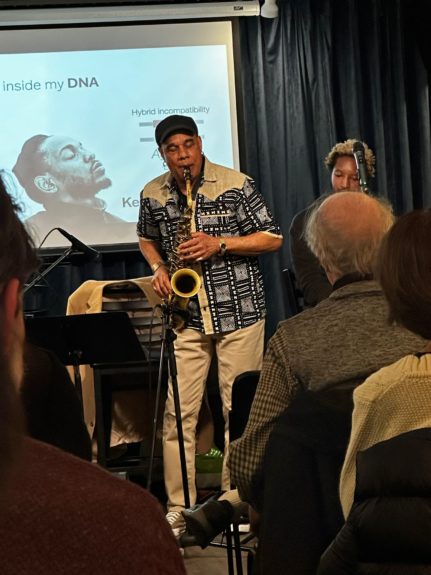

We were played into the theme of the event — evolution. Like those around me, I listened, entranced, as T.K delved into the history of jazz performance and its evolution. His ‘saxophonic’ tribute paid homage to the various eras of jazz, starting from the second line rhythm in the New Orleans funeral band tradition, then moving to the vibrant swing genre with its iconic melodic riffs. This evolution progressed into the asymmetrically phrased, fast-tempo bebop, and finally concluded with a version of improvisational contemporary jazz. With just his saxophone and piano accompaniment, T.K created a historical soundscape in which audiences could navigate through.

He created the perfect introduction to evolution that would then be used by evolutionary biologist Wyatt Toure to set up the research he does. Wyatt is interested in looking into the diversity that occurs in nature and the central question he tries to answer with research is “how did all of this get here?” He attempts to answer this question by looking at deer mice and their ability to adapt by natural selection as a means of evading predators. Deer mice, like many other species, are subject to the forces of natural selection, a fundamental mechanism in evolution. Natural selection involves the process by which organisms with traits better suited to their environment have a higher chance of surviving and reproducing, passing those advantageous traits on to their offspring. This continual process over time leads to the adaptation of species to their specific ecological niches.

Wyatt uses this example of adaptation in evolution to draw parallels to hip hop. Just as genetic material is replicated in biological evolution, hip hop artists replicate snippets of existing music through sampling. By incorporating elements from diverse genres, eras, and cultural contexts, artists create a mosaic of sound that reflects the rich history and diversity of music. This replication process serves as a bridge between the past and the present, linking different musical traditions. Wyatt explored how mutation in music is a dynamic process that involves cultural adaptation and innovation. Artists navigate the cultural landscape, drawing inspiration from their surroundings, experiences, and musical influences. The ability to adapt and reinterpret existing musical elements is a key factor in the evolution of hip hop as an art form.

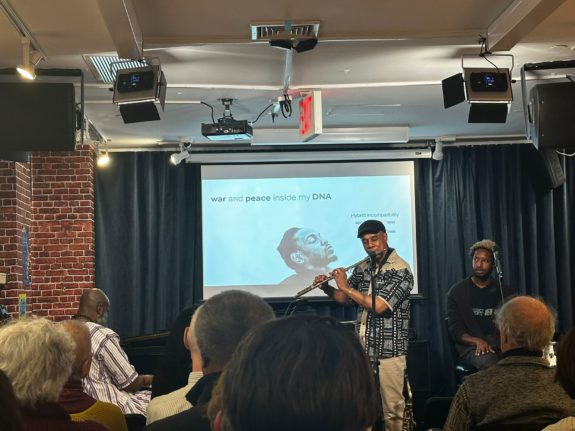

This brought the conversation to T.K Blue and the topic of composition as a means of trial and error. T.K Blue highlights the unique ability of jazz to edit or refine musical “mutations” through improvisation. In the context of jazz, improvisation allows musicians to spontaneously create and modify musical elements during a performance. This process is akin to genetic mutations in biological evolution, where variations are introduced and selected based on their impact. He exemplified this through a performance of his original composition “The Last Goodbye” on the flute. Through 8 bars he demonstrated how changing a single chord or even a note could change the entire complexion of a musical piece. This editing process aligned closely with what Wyatt would talk about next: hybridization.

In evolutionary biology, hybridization is a phenomenon where two distinct species engage in interbreeding, leading to the creation of offspring with a combination of genetic characteristics from each parent species. This process typically occurs when reproductive isolation between species is not complete, allowing individuals from different gene pools to mate. The resulting hybrids exhibit a blend of traits inherited from both parent species, contributing to genetic diversity. Hybridization can take place between different species, subspecies, or even populations within a species. The offspring, known as hybrids, often display a unique set of characteristics influenced by the genetic contributions of both parental lineages.

One noteworthy aspect of hybridization is the occurrence of introgression, where hybrids backcross with one of the parent species. This can lead to the transfer of genetic material between species and plays a role in shaping the genetic diversity of populations. Hybridization has important ecological and evolutionary implications, potentially contributing to the formation of new species with traits advantageous for specific environments. However, it also raises conservation concerns, particularly when anthropogenic activities disrupt natural barriers between species, facilitating increased inbreeding. Wyatt spoke of how conservation biologists, like himself, grapple with the complexities of hybridization, carefully considering its impact on biodiversity and the potential threats it may pose to the genetic integrity of endangered populations. He completed this section of his talk by stating “hybridization is specific and not always perfect.”

The collaboration between T.K Blue and Wyatt during the final portion of the event marked a poignant convergence of evolutionary biology and jazz, exemplifying the dynamic interplay between these two seemingly distinct realms. The chosen composition, “For Ernie,” was performed in a completely “free” manner, as T.K. described it, allowing for a spontaneous and unrestrained expression of musical creativity. The audience became spectators to an improvisational masterpiece, witnessing the live adaptation of the piece to a different tempo. This live adaptation mirrored the principles of evolutionary biology, where organisms continuously adjust to their surroundings over time. T.K.’s ability to modify the tempo and structure of the piece in real-time showcased the improvisational nature of jazz, drawing parallels to the adaptive processes seen in the natural world.

Through this performance, T.K. Blue conveyed that traditional music does not have to be primitive. By seamlessly blending elements of the traditional composition with innovative and spontaneous changes, T.K. challenged preconceptions about the limitations of musical forms, much like the way evolutionary biology challenges static views of species and their traits. T.K.’s explanation that, similar to nature, musical adaptation takes time, added a layer of depth to the performance. It emphasized the patience and gradual evolution inherent in both natural processes and musical creativity. This insight suggested that, like organisms adapting to their environments over generations, the evolution of musical styles and expressions is a gradual and ongoing process that unfolds over time.

T.K. Blue and Wyatt Toure provided a captivating synthesis of evolutionary biology and jazz, showcasing the parallels between the adaptability of life forms in nature and the transformative nature of music. The night of music at the National Jazz Museum in Harlem not only celebrated the intricate relationship between science and art but also invited the audience to contemplate the shared principles of adaptation and evolution that permeate both realms.

To hear T.K Blue’s discography, click the link here. To learn more about Wyatt Toure’s work, click the link here.

Images via author

0 Comments

0 Comments