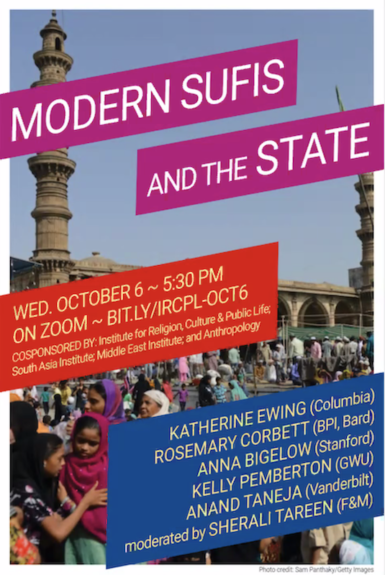

On Wednesday, Staff Writer Charlie Bonkowsky attended “Modern Sufis and the State: The Politics of Islam in South Asia and Beyond,” a book talk and conversation between several of the professors who contributed articles or edited the new volume.

“I said to him, ‘your grandfather knew the Shah,’” Professor Rosemary Corbett recalled of the time she found out her date was a member of the Rockefeller family, “‘and I don’t think we should have anything to do with each other.’” The complicity of scholars who work with institutions like the Rand Corporation or the Rockefeller Institute, even with the best of intentions, was the underlying thread which linked each of the scholars’ discussion points. Though these organizations ostensibly aim to promote modern liberal democracies in South Asia, they often result in harmful consequences. The conversation between these professors was sponsored by the Institute of Religion, Culture, and Public Life at Columbia, and moderated by Professor SherAli Tareen, Associate Professor of Religious Studies at Franklin & Marshall College.

Modern Sufis and the State was a book born from a workshop that asked the academics present to link Sufism—often seen as the ‘mystical, apolitical’ side of Islam—to the creation of Westernized, neoliberal societies. Instead, it critiques many of the paradigms under which Sufism is viewed, and provides a much more complex view of how Sufism interacts with political and religious communities.

This was not a talk for beginners. The five professors who spoke had all collaborated on the book, and thus assumed a basic knowledge of Sufism and its role in Islam, how Western scholars and state-building projects have viewed its potential, and the deleterious effects of such Western efforts in countries like India. Professor Kelly Pemberton, of George Washington University, laid out five common paradigms about Sufism the book seeks to address and complexity, which, though it came in the middle of the talk, offered a useful framework for how their conversation was laid out:

The first paradigm was the general Western image of Sufism, and the romanticized concept of the ‘peaceful, tolerant’ Sufi that fails to be borne out by observations on the ground—it’s, quite simply, more complex than that. Pemberton pointed out that many of these beliefs are codified because networks are reliant on the same insular groups of scholars, who therefore reinforce the same simplistic images. In a similar vein was the second paradigm, which pointed out that the historical and intellectual traditions of Sufism are richer than they are commonly boiled down to. The distinctions between Sufism and ‘fundamentalist’ Islam are more porous than believed, and, as Corbett—a fellow at the Bard Prison Institute—pointed out, the very concept of fundamentalism is originally Protestant. Only recently have scholars attempted to universalize this fundamentalism to other religions. Both Professors Anand Taneja (Vanderbilt University) and Anna Bigelow (Stanford University) also spoke at length on the poetry of Sufism, including that of Allama Iqbal, who wrote of Western civilization “God’s world is not a shop!… The nest built on the weak branch will not be stable.” As Bigelow noted, Iqbal’s poetry has been viewed as prophetic, a critique of Western instrumentalization of Sufism to serve its own values in South Asia and worldwide.

A large portion of the talk centered around the third paradigm: that Sufism is seen as apolitical. Professor Taneja disputed this at length, noting that, for many, the authority of a Sufi religious leader rivaled or eclipsed that of a political leader. Citizens can, in essence, be part of “an alternate kingdom…by the grace of the saint.” And as Pemberton pointed out, Sufi religious communities and institutions often have complex, involved relationships with local politics and politicians especially. She cited Sufi shrines as an important locus where these interactions take place, which was the subject of the fourth paradigm: how exactly that shrine culture has been viewed and interacted with on a global scale. The World Health Organization in 2002, for example, sponsored a study seeking to bridge the gap between more traditional medicinal practices and modern Western practices. Though that study went well, she said, there have been other points where the two have come into almost open conflict.

Finally, the fifth paradigm centered around how the role of Sufis is evolving and changing with new digital infrastructure and simple generational turnover. Professor Katharine Ewing of Columbia University, one of the book’s editors, recalled a conversation in Fez, Morocco with the founder of a Sufi music festival. He was disappointed that the “Sufi of his grandfather” wasn’t being embraced by the younger generation, so he convinced the king of Morocco to sponsor the festival. Examining how this role continues to evolve is one of the most important things scholars in the field can be doing currently, she said, and the book serves to “clear the ground” of many of these misperceptions that have driven policy and outreach towards Sufis for so long.

Reading Modern Sufis and the State will certainly require a greater understanding of contemporary assumptions about Sufism and Western state-building efforts in South Asia than I had attending the talk, but I found it heartening nonetheless to see, as Professor Taneja described it, “excellent academic integrity.” Though the book—and indeed, their research funding—was dependent on the sponsored question and underlying, misguided assumptions about Sufism, these academics nevertheless took it upon themselves to step back and provide a more accurate depiction.

Event photo and banner via Zoom screenshot

0 Comments

0 Comments