News Editor Victoria Borlando interprets the purpose of the Columbia Core very literally, using everything she “learned” from Columbia in life’s most perilous feat: surviving the 1848 Oregon Trail.

What is the Oregon Trail? Well, simply put, it’s a historic migration from the 1840s at the height of the US’ western expansion more commonly known as “Manifest Destiny.” It offered the pioneers, often from the settled Midwest, a new chance to make their own in the world, claim their own land, and tame the “wild, wild West.” But what is The Oregon Trail?

The Oregon Trail is a popular video game first released in 1985 that is supposed to educate the player on the perils and hardships of the 19th-Century journey across the American Wild West. In the strategy game, the player creates a “party”—a wagon leader, another adult, and three children—and guides them through the trail. The goal: to make it to Oregon with at least one member alive. Aside from hunting, crossing rivers and mountains, and avoiding snakes, the player must also manage supplies and the overall health of the group, regulating food rations, rest time, and the pace of the wagon. For a simple prompt-style game (that doesn’t last long if you’re bad at it), there’s certainly a lot involved.

Oh, and there are, like, ten ways to die. And you really can’t control most of them. And the game is surprisingly authentic to the time period (a win for history majors and gamers alike).

So, naturally, I asked myself: if I apply my knowledge gained from the Columbia Core—the “cornerstone” of my education—to my decision-making process in one sitting of The Oregon Trail, will I be able to save most of my party? After all, according to the Columbia College Bulletin, “ The central intellectual mission of the Core is to provide all students with wide-ranging perspectives on significant ideas and achievements in literature, philosophy, history, music, art, and science.” In other words, this unique education system better give me the skills necessary for survival, not just the correct answers to questions about Greek mythology on Jeopardy!

Thus, join me on my (Columbia) journey; see how I apply the lessons from Literature and Humanities, Contemporary Civilizations, University Writing, Frontiers of Science, Art Hum, and Music Hum to the iconic video game, The Oregon Trail. And then, after this little “Let’s Player” moment, I will have the answer to this essential question: Is my Beginner’s Mind going to help me to survive the infamous Oregon Trail?

Let’s meet my party!

The Oregon Trail video game allows the player to write the names of all the members of the family, so, when it’s time to write something down, it’s time to call upon my knowledge from University Writing! Here’s my interpretive problem: will naming my characters establish an emotional connection that will later come for me in the most sinister way? Absolutely! So, in order to prove that, I am going to use some literary devices, symbolism, and all that UW jazz, and I will name my characters and/or authors from Lit Hum books I have a deep, emotional attachment to:

- The Wagon Leader: Achilles, named after the Greek warrior, Achilles.

- Helen, the mother and named after Helen of Troy.

- Dante, the first child and named after the author of Inferno.

- Elizabeth, the second child and named after Elizabeth Bennet of Pride and Prejudice.

- Michael, the last child and named after St. Michael the Archangel of John Milton’s Paradise Lost.

And we’re off! With $160.00 in our pocket, my party and I have departed Missouri on a beautiful April day, and we have begun our personal odyssey to the American Promised Land of Oregon.

Encounter #1: The Kansas River Crossing (April 8, 1848) – Before my family is a river (625 feet wide, 4.3 feet deep) we must cross to continue on the trail. According to the game, I may try to ford the river, turn my wagon into a semi-functional boat and float across, take the ferry, or wait until conditions to improve. So, this is an estimation and judgement problem. Naturally, I’m going to apply my knowledge gained from my Frontiers of Science days. Switching to my science brain—which I turned off immediately after I turned in my Fro Sci final last year—I noticed that if I work with the water, there would be less friction, and the risk of wrecking my wagon and/or losing an oxen would be less. Furthermore, the river is deep enough for me to float across, avoiding putting my oxen into any discomfort by half-trudging along the floor. The weather is fair and warm, so I know precipitation will not be a factor in my decision. Therefore, according to the Environmental Science unit from Fro Sci, I don’t have to rest and wait for conditions to change. I could stop wasting time using my Beginner’s Mind and spend money for the ferry, but unfortunately, Principles of Econ is not in the Core. Thus, balancing a budget is beyond my capabilities. Thus, I caulked my wagon and floated it across to avoid injuring my oxen and spend as little time as possible. Success! My wagon made it across the river with no problem! Thank you, Frontiers of Science, for teaching me enough physics for me to know how water, friction, depth, and boats work.

Elizabeth gets dysentery on May 14, 1848. After resting for three days, she gets better. Unfortunately, my knowledge of diseases from Fro Sci cannot help me here, as none of those medical advances existed in 1848 Middle America. We’re going for historical accuracy here.

Encounter #2: Running Out of Food Outside Fort Laramie (June 4, 1848) – Right, we don’t have any food, health is poor, my oxen are tired, and there’s nothing around for a solid 130 miles. However, I’ve got a pocket full of bullets, so you know what that means! Huntin’ time, fellas! Now, here comes the fun part: what class from the Columbia Core will help me with hunting? This looked like a job for philosophical debate, which can only be found in the fan favorite, Contemporary Civilizations. Though smaller animals look like they would be easier to kill, I need to get bigger animals in order to get more food with fewer bullets. And even though animals die no matter what I choose, if I kill fewer animals while not sacrificing the food supply for my party, the majority of the beings involved profit. So, I choose to only aim for deer and bears in order to get the most pounds of food with the least amount of murder and bullets. Absolute failure! Turns out philosophy and morals don’t mean shit when you don’t know how to point and shoot, and you miss every single animal! Contemporary Civilizations didn’t account for the speed of the larger animals, nor did it think of the squirrels’ moxie. (NOTE: I did try to hunt again, and after discarding the CC strategy, I managed to kill two deer and a rabbit. Call me Annie Oakley, I guess!)

Helen is overcome with exhaustion on June 22, 1848. She complained for the three days it took to arrive at the South Pass, but once we got there, we rested for a week. Helen’s okay, and no one is dead, but I’m bitter that we lost precious time.

Dante breaks his arm on July 2, 1848. All he had to do was sit there; it’s not like I’m making him go through the Inferno again. He’s fine, though…at least I think he is. He’s not dead!

Encounter #3: Fork in the Road (July 18, 1848) – Oh, no! How Frost-ian is this situation my party found itself in! We could either head toward the Green River Crossing (closer, more direct route to Oregon, but it goes to a landmark instead of a fort), or toward Fort Bridger (further away, past some mountains, but brings you to a fort). It seems like it’s time to use poetry analysis skills à la Lit Hum to see if Robert Frost has some answers for us. According to “The Road Not Taken”, “Two roads diverged in a yellow wood […] / And looked down one as far as I could / To where it bent in the undergrowth; / Then took the other, as just as fair, And having perhaps the better claim, / Because it was grassy and wanted wear…” Taking these couple lines, one could interpret that the first path, bending in the overgrowth, is often the path that leads to a place unknown. The theme of hiding is common within poetry in Western tradition, often implying either manipulation of the truth and reality, or a sense of blind ignorance, unable to see the future clearly. Thus, if we were to apply this first road to one of the paths before me, I would say that the mountain route would best fit this description. One never knows what lurks in the mountain—whether predator or prey—and the bumpy road could endanger my family’s lives. Furthermore, though it promises a direct route to a fort, saving my party from running out of supplies, it still remains unpredictable. However, the other path heading toward the river is much clearer, providing a situation I’ve encountered and overcome before. However, is the safest option really the one that will give me the most benefits of the journey? Is “safe” necessarily bad? Frost says, “Though as for that the passing there / Had worn them really about the same…” thus, both roads have been taken before by many parties before me, so it is entirely up to me at this point. Thus, I took the more direct route to Oregon, the Green River Crossing, and thanks to Frost, “I took the one less traveled by, / And that has made all the difference.” Success! No one died, and we made it across the river in two-days’ time! Whoever said Lit Hum was useless obviously doesn’t know the true power of poetry…

Dante gets lost September 29, 1848. We lost four days, and I will definitely not forget that. I now know who my least favorite party member is.

Helen died of a fever on October 4, 1848. Pretty-boy Paris wouldn’t have let this happen.

Elizabeth died of cholera on October 26, 1848. We didn’t even get to have an enemies-to-lovers plot…

Michael died of a fever on November 4, 1848, even though archangels were never alive in the first place.

Of course, I’m left with the kid I declared my least favorite. I am offended and disheartened. However, that did not last very long because:

Dante died of the measles on November 21, 1848. Even though I hated him, I hope he’s happy snuggling Virgil Beatrice in Paradise.

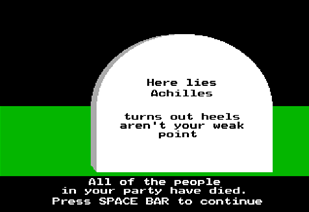

Achilles died of the measles on November 23, 1848. I am a terrible god.

So, I didn’t even make it a year on the journey, but I did travel about 1,870 of the total 2,170 miles of the Oregon Trail. Furthermore, I was able to make a lot of literary references throughout my family’s own odyssey (naming my father “Odysseus” was a missed opportunity, in retrospect). So, if I could use my Fro Sci brain one more time and do a little math, I can say that the Columbia Core can help you survive approximately 86% of life’s most difficult trials. However, this exercise helped me to learn a lot more about myself—especially as a student of the famous academic program that is the Columbia Core:

- Western Art History and Western Music history are, I’m sure, important to know if you want to be culturally aware and “smart.” However, distinguishing your Bach from your Beethoven, your Manet from Monet, will absolutely not save your child from dying of the measles. I appreciate these mandatory courses, but there will be no Starry Nights to see if I die of cholera, Vincent Van Gogh.

- Maybe—and I’m so sorry to admit this—we do need a Math core. I started with $400, immediately spent over half of it for supplies, and spent the rest on bullets and clothes, which all perished in a wagon fire incident. Turns out, money is very, very necessary for survival, and it sucks that it’s the hardest thing to acquire after countless hours of hard work. Needless to say, Math may be too important for me to neglect, and the Core has no “manage your money like an adult” section. No, I will still not take Principles of Econ.

- CC makes my brain hurt, but I guess the judgement for resting, saving bullets, and rationing food came in handy from time to time. It didn’t help me with hunting, though, and I had to quickly abandon my moral principles to feed my family. After all, what’s a “natural state of man” to some guy who’s hungry?

- Most of the things that happen in life are beyond your control, and no amount of skill and experience can prepare you for the hardships of the reality given to you. Yes, you will have to make a lot of decisions while on the road, and your education can and will help you, but it is important to realize that most things just…happen. Chance is neither friend nor foe on the harrowing Oregon Trail. And finally,

- You will seriously read anything I write so long as it’s mildly entertaining. Godspeed, you.

If you would like to play The Oregon Trail, the 1990s version is free and can be found here. But make sure you finished all your reading for the Core. You should really take advantage of that 86% success rate.

“It’s more than a game… / Life is really great… / On the trail to Ore-gate!” via Flickr

Human Empathy At its Finest via Internet Archive

Have All The Greek Heroes Fallen? via Internet Archive

0 Comments

0 Comments