On Wednesday, The Center for Science and Society hosted a lecture by Elaine Ayers – “Three Inches Deep of Wet Moss,” as a part of their New York History of Science Lecture Series sponsored by Columbia University. Ayers spoke about her moss research and its role in colonial plant transportation.

In her lecture, Dr. Elaine Ayers, a visiting assistant professor at New York University and moss enthusiast, delved into the botanical and political history of moss as a packaging material and specimen during the 18th century.

The tale starts with John Ellis, an English naturalist, who mentioned the plant in his pamphlet, Directions for Bringing Over Seeds and Plants from the East Indies and Other Distant Countries. He noted the difficulty of keeping fragile plants like citruses and orchids alive over long sea journeys and suggested moss, considered a less valuable organism, as an effective way to safely cushion specimens in their crates. Many ships had been previously using sawdust, but this did not solve the many issues sailors had with mold and rot. Moss, however, was equipped to stave off rot and cushion the plants to bring them safely to their destinations. We now know, Ayers explained, that high-acidity moss is anti-fungal, which is part of the reason why it was so successful in this role.

By the end of the 18th century, natural history institutes were instructing naturalists and sailors on how to collect moss. This teaching, alongside the invention of glass boarding cases, made transport much more viable.

Transportation cushioning was not the only use of moss at this time. It also held great economic value for Indigenous people, who used it to craft diapers, line coats, and cushioning for seats and beds.

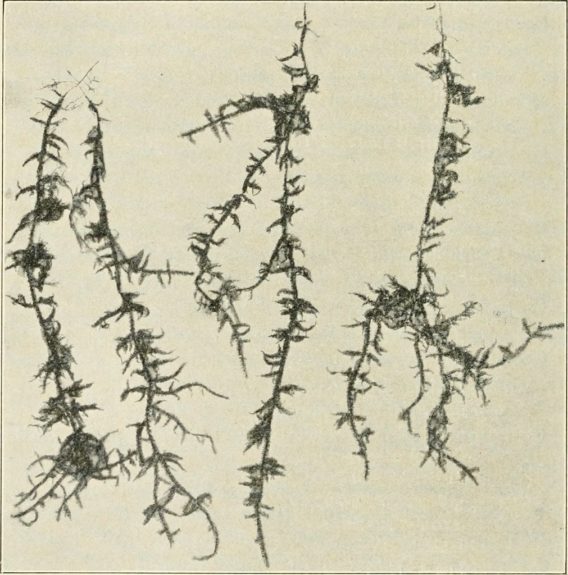

Ayers explored this idea when discussing naturalist James Motley, specifically in relation to a specimen originally collected by Motley and found at the New York Botanical Garden. Motley was born to a merchant family. Though he had great passion for collecting plants, he relied on surveying coal mines to make a living. In his 20s, Motley found himself bankrupt, and moved to Borneo to work at a coal mine in the region. This is where his most notable botanical work occurred, and where the specimen of interest was collected. He spent some of his time at the mine, but was fascinated by the diversity of flora on the island, saying nothing could describe the jungle. Among his larger collection were 200 species of moss and lichen. Much of this moss was collected by Indigenous naturalists from Borneo, who were much more knowledgeable about the area and knew how to collect fragile plant specimens. Motley was in debt at the time, so hiring indigenous plant collectors highlights how valuable they were to him. After collecting these specimens, Motley sent them to moss expert William Mitten, with whom he had a working relationship. Eventually Mitten’s daughter, Flora Mitten, would inherit his herbarium and donate it to the New York Botanical Garden. Motley’s moss specimen has survived over a century, a testament to moss’s longevity.

Ayers also spoke on the work of Mitten, along with Alfred Wallace and Richard Spruce, specifically how their writings related to moss’s primordial quality and its use as imagery for the sublime tropic. During Spruce’s travels in the Amazon, he described entering a mossy grotto as stepping into a place frozen in a past time. Since moss has been around even longer than trees, this primordial quality is something that many naturalists have noted. This connotation has remained with us, and in modern times moss is often seen in images of idyllic tropical climates, exemplifying how the plant has evolved.

There is so much more information about moss to look into, including greater explanations in Ayers upcoming book. Her focus is divided between a labor-focused approach to moss, and viewing it through an Indigenous perspective. With ancient origins and broad applications, moss has revealed itself as an unexpected but important part of human history.

Image from “Contributions to the New York Botanical Garden” page 387

0 Comments

0 Comments