Staff Writers Gina Brown and Ava Schwabecher attended the cyanotype and photozine workshop hosted by Grace Li (BC ’24), a student and the Barnard Zine Library (BZL) assistant.

Cyanotype is a 170-year-old cameraless photographic process that captures shadows of space through the use of UV-sensitive chemicals, materials from the natural environment, and sunlight. Hosted at the Barnard Zine Library in Milstein, Grace Li brought this archival process to the larger Columbia community. This workshop centered on the history of photozines and the process of making cyanotypes.

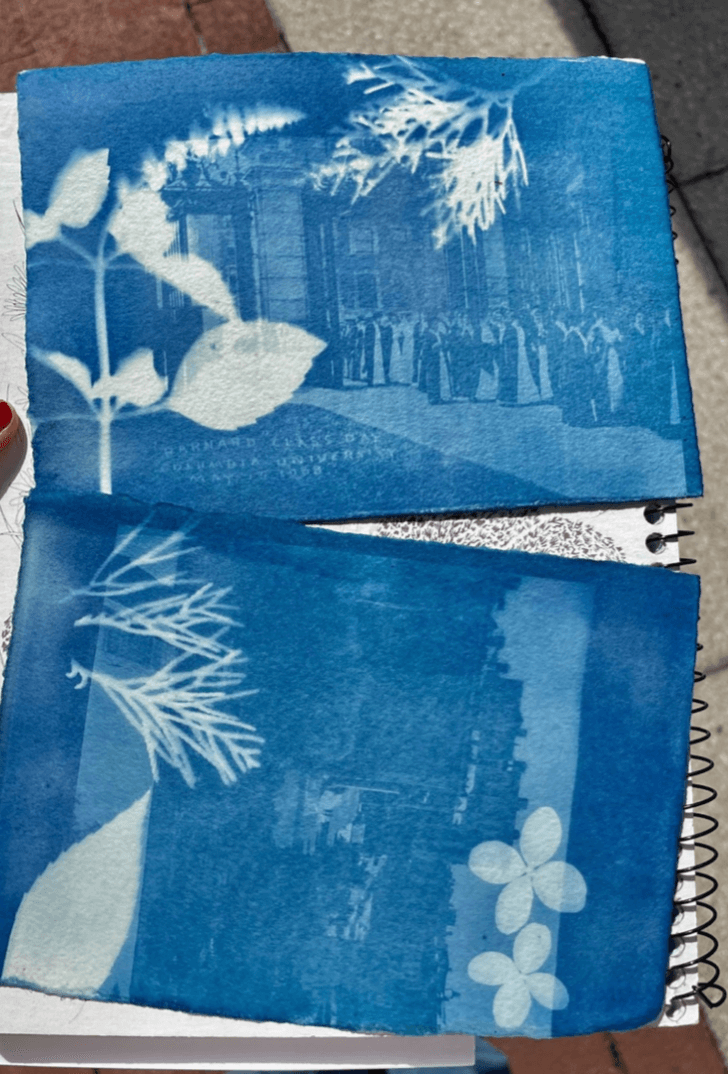

When we walked into the BZL on Friday, Grace was laying out leaves and flowers she gathered around campus and archival photo negatives of Barnard from as early as the 1890s. We also noticed two zines placed at every seat at the table: a curated reference zine for participants to gain more knowledge about the archival photographs of Barnard, and a photo zine—an arrangement of photos within a zine that can employ text but is often purely visual—of cyanotype prints made in a previous workshop last spring. Grace also distributed a variety of photo zines from the Barnard Zine Library intended for students to gain inspiration.

The theme of this workshop was “Built and Imagined Environments,” encouraging students to reflect on how both students’ relationships with Barnard and the physical campus have evolved over time. Grace also shared that part of her love for cyanotype centers on the inherent ephemerality in the prints. Because cyanotype prints fade over time, it allows us to see the real tangible impact of time on photography, which is often lost in the current emphasis on digitality in photography.

Sharing of materials was encouraged and necessary as the BZL was filled with students excited to create prints for their photo zines, postcards, and dorm decor. Grace encouraged us to cut up the photo negatives of Barnard and play around with layering the photographs and gathered leaves and flowers. Some students even chose to employ one material found abundantly on campus in their printing—lantern flies. We layered the materials over UV-sensitive paper to capture the imprints of our chosen elements, creating outlines of different shapes and color gradients.

When it came time to develop our prints, groups walked to the Diana Center and placed them in direct sunlight. Students were encouraged to overlay their cyanotype prints with a transparent acrylic sheet to protect them from the wind. While my print blew away several times, I was reminded of the physicality of the cyanotype process and the intention and care it requires. Compared to the instantaneous gratification of taking a photo on your phone, more excitement and joy come with unveiling the unique way a cyanotype develops.

After 15-20 minutes, participants were encouraged to wash their prints under running water to fix the image created so the sun would no longer affect it. We were left with cyanotypes’ characteristically deep blue prints, with negative white space where our materials were placed.

Cyanotype is truly a unique method of photography. It’s ever-changing, as Grace noted, that the colors can deepen or lighten depending upon continued exposure to the sun over time. Instead of you taking a picture of something in the external world, you are composing an image with your very hands. We encourage everyone to come to another one of these events sometime in the near future, and to create one for yourselves!

Interviews with Claudia Acosta and Grace Li:

Claudia Acosta, (They/Them) Zine Tech at Barnad’s Library

Kyle Murray: You had mentioned to people who walked in the history of the cyanotype workshops. I was curious how these came into existence. How did they start? And also, why is the zine library a kind of “perfect pair” between the two [Photo Zines and Cyanotypes]?

Claudia Acosta: There’s a kind of collage ephemerality appeal to it; you can’t control how the final product is gonna look and I feel that parallels some parts of zine making. You don’t know what it’s gonna be. It’s kind of scrappy. It’s not gonna come out how you want it half the time—things fall off the page that you’re building, like, as you scan it, (which often happens to me). There’s a long history of photo zine stuff and I think this collaborative zine that Grace made from the past cyanotype workshop brings it all together,

KM: Besides the work that Grace has done, are there any other notable examples of cyanotypes in the zine archives here at Barnard?

CA: I’d have to do a catalog search for you to find them!

Grace Li (She/They), Barnard ’24

Kyle Murray: First: name, pronouns, and the general who, what, where, when, and why.

Grace Li: I’m Grace, I use she/they pronouns. I’m a senior at Barnard, studying CS and English. I’m from New Hampshire.

KM: What drew you to cyanotypes as a medium? And how does that relate to your majors of English and CS—this is neither of those. So how does all of it fit together within your own personal journey?

GL: Definitely! I started photography when I was a sophomore in high school—I started in digital photography. And then during my senior year, I got more into film photography. Ever since the pandemic, I focus a lot more on the slower-making process of analog photography, polaroids, and film. Also over the pandemic, I explored more cameraless photography techniques like lumen printing and cyanotypes because I think it’s really cool how you can just capture the essence of things, their shadow or, not sticking to a very realistic portrayal of objects. I think I still continue, playing around with cyanotypes and lumen prints because it’s a lot more fun and there’s no like standard that you’re striving for. I think, especially with digital photography, it’s very easy to focus on details and things like that. So I like cyanotypes—it feels a lot more playful to me.

KM: Last semester’s theme was about found materials whereas here it’s Built and Natural. How do you think those ideas tie into cyanotypes and are there any progressions in the future, whether next semester or beyond?

GL: So last semester’s workshop was a lot about piloting this idea. I’ve been really wanting to do photozine events and the director of the zine library is supportive in creating the space for me to explore things. So the theme last year was very straightforward—things you find around campus to illustrate how different students interact with the surrounding communities and what we can learn from ourselves to the objects we find or find interesting.

This year, I didn’t want to do the same as last year, so I was thinking about different variations on that. I was looking a lot into the digital collection for printing transparencies, which is like one step up from last year but still in line with found materials.

I think in future iterations—I’m not sure. There’s so much more to do. Right now people are making individual prints. I think making more large-scale projects in the future—like a big collaborative cyanotype—would be cool.

KM: Another question is about the role of the archive in this. The archive is, number one, a place that’s supposed to keep objects stored, but there is also damage or violence that can exist in the archive. How do you view this work of bringing these old photos to light in this new way—this new form of photography—are there any marriages or any thoughts or philosophies that guide you?

GL: I think there’s a lot to unpack when you do think about archives, whose work is “deserving” or has been “deserving” in the past and being archived, or whose work has been taken from them without their consent and archived within the collections. I think a lot of it is thinking about consent and ownership of institutions over these personal materials and things like that. But at this workshop in particular, I just wanted to expose more people to the Barnard archives in general and as a very introductory starting point—not at all comprehensive of the interesting and complex questions that should be asked about “what are archives” and “what is their purpose in academia or our personal lives.” But through this experience, people can ask those really important questions.

Just thinking about zines. themselves. There are a lot of conversations happening around people who do not want their zines to be archived because of how personal they are and thinking about what it means for our stories to be preserved in this way and at institutions versus the ephemeral nature of just letting our stories exist to the people we come in contact with and maybe not existing, quote-unquote, forever in these institutions. There’s a lot of interesting, overlapping questions.

Cyanotype via Flickr

Event images via Authors

0 Comments

0 Comments