In 2022 and 2023, RAs at Barnard and Columbia made history by becoming only the eighth and ninth RA unions in the country. This semester, current and former members of the Barnard RA Union and CURA Collective sat down with Bwog to tell the story of their eventful first years.

The Beginning

It was the spring of 2022, and, the way the RAs tell it, they had come to a realization: the position was far from equitable.

That March, on Columbia’s side of Broadway, low-income RAs—those whose costs of attendance were largely covered by institutional aid—had taken notice of the fact that their compensation was much different from that of their higher-income peers. At the time, the lion’s share of compensation for both Barnard and Columbia RAs came in the form of the colleges covering their housing costs, in addition to a small stipend—around $1,000 per academic year. For RAs whose housing was already covered, in part or in full, by financial aid, that element of their compensation was effectively erased.

“People who were on full financial aid were only receiving their $1,000 stipend,” explains RA Hannah Puelle (CC ’25), an organizer with the Columbia University Resident Advisers Collective (CURA), the University’s newly-minted RA union. “When you divide it by the number of hours they worked, it came out to less than $2 an hour.”

Meanwhile, at Barnard, another issue was brewing. It was May, and the small contingent of Barnard RAs who planned to work on campus that summer had learned—after signing their summer contracts—that they would not be offered meal plans as part of their compensation. For RAs in Elliott Hall, a corridor-style dorm with no refrigerator access, conditions seemed especially dire.

Still, the situation grew more tense from there. When a small group of summer RAs, led by Aditi Misra (BC ’23), inquired about their lack of meal plan, they were told by the Office of Residential Life, which oversees RAs, that the decision was made because they would be working reduced hours compared to their typical semester schedules. However, when they arrived for their training that May, the summer RAs soon learned some shifts would not actually be reduced, but doubled or tripled. After discussions among the summer contingent, RAs say it became clear the situation was untenable as is; either the College would walk back on its changes to the summer RA role, or the summer RAs would mount a strike.

The RAs didn’t know it yet, but on both sides of Broadway, these issues would become far more than a one-time negotiation. When they sat down with Bwog earlier this semester, Puelle, her fellow CURA organizer Carmelli Leal (CC ’25), Barnard RA Union organizer Rania Hussain (BC ’25), and former Barnard RA Hannah Yi (BC ’24) each identified that spring as a catalyst for what was to come.

Over the next year, RAs at Barnard and Columbia would see their organizing efforts snowball, from hushed conversations about the job’s many downsides to full-scale rallies in front of the offices of college administrators, to elections with the National Labor Relations Board. In fact, the groups would find themselves at the forefront of a growing labor movement among undergraduate student workers nationwide. They would make history as two of the first RA unions in the country.

Age of Dissonance

Hannah Puelle and Carmelli Leal start off their interview with a disclaimer: neither were founding members of CURA, which began organizing in the spring of 2022, more than a year before its eventual unionization. Both juniors at Columbia, the pair witnessed much of CURA’s early organizing efforts as first-years recently accepted to the RA program for the coming fall. For them, that first spring involved coming to the gradual realization that the dream job they’d recently accepted may not have been all it was cracked up to be. Beyond the understandable anxiety, the awareness that they were en route to less-than-ideal working conditions was also galvanizing for Puelle and Leal. In fact, the pair agrees that witnessing CURA’s early organizing efforts from the sidelines gave them more hope for what was to come when they officially became RAs that fall.

Back in spring 2022, after those initial conversations, RAs on the Columbia side quickly brought the disparity they’d noticed to the attention of their coworkers, and eventually to the larger community.

As RAs from both campuses tell Bwog, the role—known as Resident Assistants at Barnard and Resident Advisers at Columbia, hence the abbreviation—is a particularly intensive one. As Rania Hussain explains, “it’s not really a nine to five; you’re working where you live.” RAs arrive early for both the fall and spring semesters—at least a week before their residents move in—remain at work until after the summer move-out deadline, and work through some or all of many academic breaks. In the roster of student jobs, the RA role is one that seems to require exceptional commitment. By the time discussions about pay inequity arose that spring, RAs say they were far surpassing the hours required of most part-time jobs, even those off-campus, and, in some cases, working 24-hour duty shifts on weekends. RAs are also regularly “on duty,” a shift type that varies in frequency depending on the size of each dorm building and its RA staff. During these shifts, Puelle and Leal say RAs are often awake well into the night conducting “rounds,” which involves carefully walking through the entirety of their assigned building or buildings, checking every suite on every floor, as well as common areas, for any safety concerns. For some RAs, like Leal, this duty includes rounds at multiple buildings in the same night. Before CURA formed, Leal says a weekend duty shift at Columbia included conducting three rounds per night, the latest of which began after midnight. Still, says Puelle, there was work to be done when it came to convincing the rest of the community that organizing, much less eventual unionization, was warranted at all.

“People were like, ‘if that’s what you’re getting as compensation, just get another job,’” she explains. There was even a moment during RA training that subsequent summer when Puelle says she and other RAs were told by a supervisor, “You could get another job. They have bartending here.”

“But whatever work you’re doing,” she says, “you should be fairly compensated for it, point blank.”

As Puelle describes, those initial conversations between low-income RAs soon began to snowball. Later that spring, Columbia RAs began internally circulating a document—part open letter, part petition—demanding a change to their pay structure, as well as open communication with Columbia’s Office of Residential Life. The group ultimately decided to open the petition to non-RAs, and within a few weeks, it had received more than 1,500 signatures from students, community members, and faculty.

Eventually, a group of RAs approached the Columbia College Student Council to ask for the group’s support in demanding better stipends. But by that point, says Leal, the issue was far from reaching a resolution. “Once people had gotten together to talk about the pay issue, there was a realization that there’s a lot else that’s bad about this job.”

***

Meanwhile, at Barnard, Hannah Yi, one of 17 RAs contracted for the summer, was having a similar experience. RA training in May had brought with it the realization that not only had accommodations like meal plans been stripped, but duties had been increased. The job was feeling all the more strenuous, and the benefits were feeling few and far between.

“The new RAs were really confused,” says Yi. “The old RAs were just really annoyed.”

Reflecting back a year later, however, Yi and current Barnard RA Rania Hussain both point to even larger systemic issues that came to light when RAs realized their meal plans had been cut. (Hussain, like Puelle and Leal, was inspired to join the organizing efforts that Fall after witnessing the RAs’ early victories as a new RA.) Most prominently, Hussain and Yi say Barnard’s Office of Residential Life is far from consistent. The office is made up of three levels: Directors at the top, Residence Hall Coordinators (RHCs)—who directly oversee RAs—at the bottom, and the Community Director, a position invented that year, in between. Hussain and Yi say that historically, many of these positions have largely been filled by graduate students, creating an environment where staff turnover is incredibly common. However, Yi says the Spring 2022 semester had seen an especially significant amount.

“What we were noticing was that among the RHCs, the turnover was really insane,” says Yi, “not just because some of them were graduating. People were quitting out of nowhere.” Meanwhile, Yi says the directors who were consistently on staff were often out of touch with the needs of RAs. (Leal noted similar issues on the Columbia side, saying there were “no real mechanisms for communication between RAs and ResLife.” In turn, she says this often led to “instances of arbitrary discipline,” as the criteria for disciplinary action was handled largely on a case-by-case basis. What’s more, she says the RA experience varied “wildly” based on which member of ResLife staff was their supervisor. “The quality of our bosses, who are bosses are,” says Leal, “shouldn’t determine the quality of our workplace.”)

Reflecting on that summer, Yi recalls meeting with ResLife directors only to discover they were largely unaware of the issues with which RAs were struggling. “They didn’t even know Elliott didn’t have refrigerators. It just goes to show how out of touch leadership is.” In fact, even months after that incident, Yi recalls another instance where a ResLife director had trouble navigating Reid Hall, a dorm building in the Barnard Quad, despite having held her role for over a semester.

“She came into Reid Hall in the Quad, where three out of four of those dorms don’t have air conditioning, and she said, ‘Oh, it’s hot in here!’” recalls Yi. Later that day, Yi says the same director asked for help finding the building’s women’s restrooms. “It just really felt like, wow. You don’t even know where you work. You haven’t even done one walk in this building that you’re supposed to be responsible for.”

Thin Ice

In June, a group of summer RAs, Yi and Misra included, once again contacted ResLife directors and RHCs, CC-ing Barnard College Dean Leslie Grinage, this time armed with a PowerPoint presentation outlining their demands.

“We basically compared the hours that we were working in the Spring to the hours we were working [that summer]. We compared our position to other summer positions on campus, like [the Summer Research Institute], where [employees] get a stipend and a meal plan,” explains Yi. “We showed emails that demonstrated we should have gotten a meal plan, that that had been promised to us.”

Alongside these materials, Yi says the RAs’ message to ResLife was clear: if Barnard did not meet their demands—which at that point included an increased stipend, a summer meal plan, and reduced summer duty hours—they would begin a strike. Looking back a year later, Yi says, “we were gunning for it all. But we were doing it in the name of making a change.”

Within a day, the College had responded, affirming new summer accommodations for the RAs. They would receive a $400 GrubHub credit for securing food before their meal plans kicked in a few weeks later, their 24-hour weekend duty shifts would be reduced to 12 hours, and, finally, RAs in Elliott Hall would receive fridges.

***

Across the street, Columbia RAs were working hard to drum up support for their cause. That July, the RA organizers, now officially going by CURA, or the Columbia University Resident Advisors Collective, held their first rally—a virtual one, to accommodate RAs who had already left the city for the summer. Soon afterward, Columbia’s Office of Residential Life announced a change to the compensation structure for RAs: everyone would be compensated equally, in the form of a $13,000 honorarium payment, regardless of their financial aid status. In turn, the cost of housing would be charged on each student’s tuition bill as part of their cost of attendance. Initially optional for the 2022-23 academic year, the compensation model has since shifted completely to the new structure.

Here, Puelle and Leal start to tell CURA’s history from the first-person. Reflecting on her early days as an RA in the Fall 2022 semester, Puelle says those summer wins were bittersweet, coming with the realization that conditions for RAs existed on a delicate balance. “We realized we’d gotten these wins,” she says, “but we were cognizant of the fact that a change in ResLife leadership could mean everything we’d won would be rolled back.”

These fears, Puelle explains, made the path forward—and the goal of unionization—all the more clear. “We realized we weren’t making progress on certain issues, especially our disciplinary policy,” she says. “We had no way to force Columbia to sit down with us and negotiate these things unless we had a union.”

However, Puelle says those wins were simultaneously mobilizing and immobilizing. “They’re mobilizing,” she says, “in that people realize we can make changes, but also de-mobilizing in that once we had the payment change, there were some people who were like, ‘Okay, now I’m fine with this job, I don’t need anything else to change.’”

Convincing the RA body that one change wasn’t enough was a challenge in its own right, Puelle and Leal explain, but by October of 2022, they say the group had more than enough support to push on toward its new goal of unionization.

How A Union Is Born

Before the unionization process began on either campus, both groups had already seen some important organizing wins. Still, at the start of the Fall 2022 semester, the organizers had a long road ahead, beginning with affirming support among the student body.

Similarly to CURA, for the Barnard RAs, it was the bittersweet combination of those early wins and their continued disappointment with ResLife, Yi explains, that became a galvanizing force to continue their organizing even after the summer had ended.

“Because there were only 17 of us [summer RAs], it was very easy for us to garner collective action,” Yi explains. “We were so inspired by the amount of change that we were able to achieve that we thought looking forward into the fall, it might be a really good idea to organize something bigger and more permanent.”

And organize they did; that summer, Misra contacted OPEIU Local 153, a union that represents professional and office workers in the non-profit, healthcare, higher education, credit union, insurance, and municipal sectors in New York. As Yi explains, “We thought, if we’re going to do this, we’re going to need help. We need to be informed.” OPEIU soon connected the RAs with veteran labor organizers who spoke to them on a weekly basis during that summer and fall. “They really helped us with union building, and that whole process of creating a union,” says Yi.

That process included collecting the names of all 57 active RAs in the Fall 2022 semester and creating a spreadsheet where each was scored according to the level of support they would provide to the union.

“Our little organizing committee of maybe five people managed to talk to all 57, and all of them, minus two, were totally on board,” says Yi. “I think it worked particularly well at Barnard because we’re such a small group. At a bigger school, it would not be feasible to have conversations with everyone and really understand what they’re thinking.”

The Barnard RAs would ultimately choose to unionize under OPEIU as their parent union. This was one area where they notably differed from CURA, which later became the first independent RA union in the country. As Hussain explains, “[OPEIU] helped us throughout this entire process. We work with their lawyers, who sit on our bargaining table so it’s not just us.” Underneath the parent structure of OPEIU is a smaller group of about two to three student leaders, who have shifted over the Union’s year-long existence—as is the nature of a college organizing body.

Some important legal context: in order for students at a private university like Columbia to become legally recognized as a union, they must follow a procedure outlined by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), a federal agency that oversees labor rights for private sector employees. This procedure begins with circulating a petition, gathering signatures from the body of student employees verifying a significant portion is in favor of unionizing. Next, the students typically serve this petition to their employer and request that the university voluntarily recognize them as a union and enter into bargaining of its own accord. If the university refuses, the students will then pursue an official union election with the NLRB, in which the employee body will vote on whether to unionize. Because private colleges and universities are bound by NLRB rules, if the group wins its election, it is officially recognized as a union under federal law and is entitled to bargain with its university whether that university has decided to voluntarily recognize it or not. In some ways, that means this process of voluntary recognition is largely an opportunity for colleges and universities to send a message, establishing themselves either as pro- or anti-student worker union.

On the ground, this meant that that same organizing committee must once again track down all 57 RAs, this time to collect individual signatures—on paper, Yi specifies, noting the analog nature of the whole process—verifying their support for a union. To move forward with unionization, RAs needed to prove that a significant majority of employees were in favor of moving forward. In total, they got signatures from over 90%.

When it came to unionizing, the Barnard RAs were first to the punch. On October 3, the group announced via social media that it had officially filed for union recognition with OPEIU Local 153, alongside a video of RAs delivering the petition to the office of then-Barnard President Sian Beilock (Beilock was absent at the time). Four days later, the newly formed union held its first rally, gathering in front of Milbank Hall, where Beilock’s office was located, to demand recognition. A week later, Barnard officially declined to recognize the union. At that time, the College told Bwog it had asked the group to “engage in a fair and democratic election process overseen by the National Labor Relations Board to ensure that all voices of the proposed unit are heard.”

The Barnard RA Union held its NLRB election in November 2022. After collecting handwritten signatures in person from RAs earlier that semester, organizers now had to convince all 57 to make the trek to the Diana Center one Friday in November, where they would cast physical ballots in a box counted by NLRB representatives. Ultimately, the group won its union election in a landslide, with 47 yes votes and just two nos.

Still, negotiations with the College weren’t easy from there. Even before their official unionization, the union publicly took issue with the College’s decision to be represented by Associate General Counsel Rachel Muñoz in negotiations, claiming Jackson-Lewis, which employs Muñoz, is a “known union-busting law firm.” The union further pointed to a number of complaints filed against Barnard with the National Labor Relations Board over the last four years, a period during which the College was represented by Muñoz and Jackson-Lewis. The charges included Retaliation, Refusal to Bargain, and Bad-Faith Bargaining. (Indeed, though Jackson-Lewis does not self-identify as “anti-union,” the firm has made a name for itself in the last decade representing universities when student or faculty groups have attempted to unionize. Online, the firm has previously advertised its “preventive approach” to labor negotiations, which at one point, appeared to include “union avoidance training.”)

It’s on this note—victory, followed by continued struggle—where Yi says her story with the union ends. After an intense Fall 2022 semester, she took a hiatus to study abroad. When she returned this fall, she left the position entirely. At the same time, Hussain’s union involvement was just ramping up—a year later, she’s a familiar face at RA rallies outside Milbank and the bargaining table inside Sulzberger Tower. In the naturally ephemeral world of undergraduate labor organizing, Hussain, Puelle, and Leal make up a newer generation of RAs, just a year too young for the initial organizing efforts, but more than prepared to keep the movement alive.

***

In contrast to the Barnard RA Union and OPEIU Local 153, CURA is an independent union, the first of its kind in the United States. As Puelle and Leal explain, the group made that decision in part because it allows them to operate in a “very horizontal, very open structure;” there are no non-student leaders, and the union’s Organizing Committee, which meets weekly, is open to all RAs. While CURA recently elected its Bargaining Committee, students who will represent the group in negotiations with the University, Puelle and Leal say even that structure is relatively non-hierarchical.

Still, while CURA’s structure may be different from the Barnard RA Union, its unionization process played out in much the same way, though, Puelle and Leal note, perhaps more sensationalized. By February, the collective had received signatures from around 70% of its unit on its petition to unionize. That month, CURA made headlines when union members attempted to deliver the letter directly to then-Columbia President Lee Bollinger, only to find his office in Low Library had been placed on lockdown.

When asked about that day, Puelle and Leal roll their eyes and make jokes about being mischaracterized by campus publications as having “stormed” Low Library. “We had some conversations about that phrasing,” says Puelle. “We weren’t trying to storm Low, we were explicitly trying not to storm Low. We were just trying to deliver a letter. A lot of us were doing a lot of work on organizing, and we just wanted to be there for the big culminating moment of it all.”

Instead, Puelle and Leal say CURA’s visit to Low that day was carefully planned. “We talked a lot about how big is too big, how small is too small, and we ultimately decided that only RAs would be going into the building, not supporters. There was a group of 10 to 12 of us.”

When the group arrived at Low that day, they quickly realized something was off. At the building’s main entrance, where students are typically permitted to enter after swiping their CUIDs, the group was held up by Public Safety officers, who told them no one was allowed in the building. “They told us, ‘we’ve gotten an alert that there are people here to ‘penetrate’ the building,’” explains Puelle. “We said, ‘oh, is that us? No, we’re just trying to deliver a letter.’”

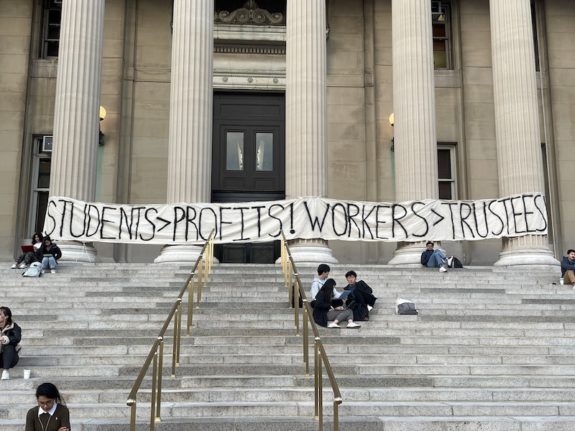

Still, the group never did get to meet with Bollinger directly. Eventually, a representative from his office met the group in the lobby and told them she would ensure the letter was delivered. Later that week, Bollinger announced Columbia would not voluntarily recognize the Union. In response, CURA changed the messaging of its pre-planned rally that afternoon—pivoting from “A Rally to Demand Union Recognition” to “A Rally for Union Solidarity.” The rally—which featured New York State politicians, representatives from other campus unions, and Corporate Fat Pig, a cousin of perennial campus labor protest attendees Scabby and Corporate Fat Cat—got plenty in the way of solidarity from student and community attendees, who showed up in droves. Eventually, the group migrated from its starting point on Low Plaza to just outside of Bollinger’s home on 116th and Morningside Drive—a message that their conversation with the President was far from over. In the crowd’s wake, signs strewn across Low Plaza read “care-taking labor is real labor” and “students > profits, workers > trustees.”

Three months later, on May 2, CURA won its NLRB election with a 95% yes vote, officially becoming the first independent RA union in the country.

New World Coming

By the time they got to the bargaining table, the organizers on both sides of Broadway were no strangers to making history. However, they’re far from the first unions to do so on campus in recent years, much less across the country.

For several years, labor-related headlines on campus were most often tied to the Student Workers of Columbia, the graduate student workers union that in 2021 organized the second-largest strike in the country when its contract negotiations with the University stalled. The strike itself—in which over 2,000 union members, many of them TAs, ceased work for over three months—was a defining moment in Columbia’s labor history. In the classroom, the absence of graduate workers effectively stalled the release of grades in a large number of Columbia courses, while outside on College Walk, union members were joined by faculty members, undergraduates, and community members in calling on the University to meet their demands. Puelle and Leal say the union’s ultimate success in ratifying a new contract also became a source of inspiration during later CURA organizing.

Still, SWC is not the only active union on campus. At Barnard, the Contingent Faculty Union represents non-tenured professors in their contract negotiations, and won a new collective bargaining agreement last year, just as things were heating up with the RAs. At Columbia, the Postdoctoral Workers Union narrowly avoided a strike last month when it reached a satisfactory contract with the University less than 24 hours before its deadline.

The labor drive has now started to reach undergraduate workers, whose path to unionization has become much easier in recent years. Until the late 2010s, the NLRB was embroiled in regular debate over whether student workers could formally be considered “employees” who had the right to unionize, an issue the agency ultimately settled in favor of the students. Coincidentally, it was a case involving the Student Workers of Columbia that finally answered this question for good when the NLRB ruled in 2016 that student workers fall under “employee” status and are thus entitled to the same protections as any other worker.

This, alongside later Biden-era reinforcement to NLRB protections—which included a threat to prosecute any university that leads its undergraduate employees to believe they aren’t entitled to unionize—opened up a new world for undergraduate labor organizing. Undergraduates, whose student status once jeopardized their ability to access protections in their student jobs, are now more empowered than ever to organize as they would in any other workplace. At Barnard and Columbia, union organizers say that change was easily felt.

“I think we’re having a labor moment across the country,” says Puelle. “The new generation is pro-labor in a way that had sort of fizzled off at some point before the turn of the century. I’m really excited to see it coming back, and I’m excited to see all the solidarity we have on this campus and across the country.”

As Puelle and Leal explain, CURA is in frequent contact with most of the University’s other labor unions, as well as with undergraduate student workers across the country. “Obviously, there’s only so much that can be said for undergraduate student labor,” explains Puelle. For one, college labor organizing is inherently ephemeral; students who lead initial labor movements tend to graduate within a year or two after their first rally, which can create struggles to keep the movement going in their wake. What’s more, “We don’t have the same political power that workers off campus have,” says Puelle. “But hopefully what’s happening is that undergraduate union organizers become regular union organizers in their lifetimes, organizing their later workplaces and increasing our union density.”

The Future

After an eventful year, both unions have spent this semester largely dedicated to bargaining. Since August, the Barnard RA Union has had seven bargaining sessions with Barnard’s General Counsel—the same lawyer who RAs say is “deliberately anti-union.” While recently, the Union and the College have found themselves held up on the issue of compensation, they plan to continue their bargaining in the coming weeks.

Meanwhile, CURA held its bargaining committee elections in October, creating an organized panel of students to represent the union in negotiations with the University. Puelle and Leal say union leaders are also still in the process of solidifying CURA’s demands. In September, CURA held a town hall where all RAs had the opportunity to share which issues mattered most to them, followed closely by a teach-in on Columbia’s history of student organizing. Barnard RAs, who most recently held a rally for fair compensation on October 20, hope to have their negotiations complete this month. CURA’s process may take a bit longer.

Going forward, Hussain says she hopes people understand that the union is, above all, rooted in community.

“It’s a group effort really. There’s been a lot of work behind the scenes by everyone involved, from new RAs to returning RAs, to friends of RAs. We’ve had a ton of support from the student body, and we really value that. It’s not like there’s just a few people leading this union effort. It’s very much a collective effort by every RA, and that’s something really special.”

Meanwhile, Puelle and Leal say they’re excited for the future, and to continue shaping CURA even after a contract is achieved. However, Puelle also points again to one of the inherent anxieties of organizing a union at an ephemeral workplace like a college. “We’re independent,” she says. “We don’t have a parent union who’s gonna preserve this organizing for us. We have to be self-reproducing.”

CURA and Barnard RAs included, there have certainly been some significant labor wins on campus since the Student Workers of Columbia staged one of the largest strikes in the country two years ago. CURA has already won a major change to its pay structure, and a reduction of rounds, the duty that Puelle and Leal say once caused the most issues among RAs. Still, when it comes to expecting changes from the University, Puelle and Leal say they’re skeptical.

“We want to be realistic. We don’t expect for all of our problems to be solved, or for us to not need to organize anymore. We’re ultimately still workers of a very, very large entity that has a history of not always doing right by its workers,” explains Leal. “But, we’re hoping to not have to consistently take escalating actions.”

“As organizers, this is a thing that we do because we care deeply about our work and the people that we work with,” Leal adds, “but it’s not a fun job. Any organizer I’ve ever talked to would tell you that if they didn’t need to organize, they wouldn’t.”

Still, the organizers are not without hope.

When presented with this question—whether CURA has any hopes for Shafik’s administration—Puelle considers for a moment. “I just hope that the new administration understands that Columbia being anti-union has not stopped workers in the past.”

“I’m hopeful. I’m not overly optimistic,” answers Leal. “I’m not expecting anything wildly different.” Still, she says, “I’m hoping some people have a change of heart.”

Header image, Corporate Fat Pig, and “Students > Profits” banner image via Kyle Murray

SWC Strikers on Low Steps in 2021 via Solomia Dzhaman

All other images via @barnardraunion and @cu_racollective on Instagram

1 Comments

1 Comments

1 Comment

@lr incredible feature about an incredible labor movement!!!