On October 17, Staff Writer Lorelei Gorton attended Music on the Brain, a conversation at the National Jazz Museum of Harlem on the emotional impacts of music with a Columbia neuroscientist and a local musician.

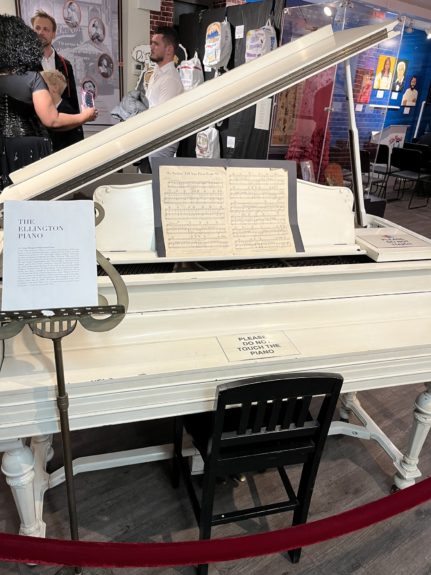

I knew I was in for a treat the moment I stepped into the National Jazz Museum of Harlem, and not just because it was warm—although my fingers were kind of freezing off from the thirty-minute walk it took to get there–or because it housed insanely cool historical artifacts, like Duke Ellington’s piano (beautiful, stunning, gorgeous), but because of its joyous, cheerful atmosphere. Unlike the previous events I’d attended in the sleek, modern Columbia buildings of the Forum and the Lenfest Center, this had a much cozier feel. (Of course, the venue being tighter contributed to this feeling too.) The audience was alive, chattering; the speakers were mingling with people who seemed to be regulars, or introducing themselves to some foreign tourists. Fittingly, a soft, running jazz tune played through the speakers.

Just after seven, the event formally began, as an introductory speaker welcomed us to the National Jazz Museum. The museum is no stranger to these kinds of events; they host 2-3 performances per week, usually free, to build community and further their mission to “preserve, promote, and present jazz music.” Tonight’s event was but the latest installment in the Music on the Brain series, which first began with former artist-in-residence Helen Sung in 2022. The series brings together scientists and musicians to examine the impact music can have on our physiological systems, including memory, movement, and, in this case, how we process movies.

The first presenter, jazz pianist, vocalist, and composer Kelly Green (which was a bit of an insufficient introduction, given her resume; she’s played at the Kennedy Center, and is a Steinway Artist, on top of having just released a new album) started us off with a discussion of music’s power to change the perspective of a scene. We watched a clip of Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, first with no sound, then with three different piano accompaniments played by Green. The first was well suited to the action–deep, ominous, lots of minor tones–and the second the complete opposite; an upbeat, jazzy, stroll-in-the-park type of music that trivialized the horror of Hitchcock’s film and sent the audience (myself included) into fits of giggles. The last was a piano rendition of John Lennon’s Imagine–which was just a total anachronistic disconnect and removed all connection between the movie and the music. Lots of audience participation was encouraged; we discussed all of our reactions to the music with our neighbors, shared with the room, and generally developed a dialogue between the presenters and the observers that made the experience much richer.

Next up was David Gruskin, a MD/PhD student at Columbia who studies how people process movies, and sensory information in general. Movies, he said, can serve as “stress tests” for emotional processing disorders like depression or anxiety by producing reactions the doctors need to analyze and diagnose subjects, like how a patient with cardiovascular disease might be asked to run on a treadmill so that his heart problems can be examined clearly. Movies “mirror what we’re experiencing as we walk through the world,” according to Gruskin, so they’re a form of what’s called naturalistic neuroscience, which uses every day, “normal” techniques to tease out scientific insights about our mental behavior.

While auditory stimuli (aka noise) activate the auditory cortex and visual stimuli (aka light) activate the visual cortex, the rich variety of input–auditory, visual, emotional, etc.–present in movies activates the entire brain. Multisensory areas, located in the middle of the brain, are responsible for this type of input processing, which involves multiple types of stimuli that are intertwined. Specifically, Gruskin mentioned the PSTS (posterior superior temporal sulcus, for those in the know) as an area that processes both sight and sound at once. An example of the PSTS at work, as we got to see, is the McGurk Effect. In the McGurk Effect, an audio of a man saying “ba-ba-ba” is played over a video of a man whose lips are making various syllables, including “va,” “da,” “ba,” and “fa.” When we watch the video, and see the conflicting visual stimuli, we can hear different syllables depending on how the man moves his mouth—but when we were asked to close our eyes and listen, it was immediately clear that “ba” was the only syllable being said aloud. This proves that our visual and auditory processing systems are closely linked, an evolutionary advantage that allows us to better communicate with and understand others.

But how does this multisensory perception differ between subjects? After all, people listening to the same piece of music, or watching the same movie, don’t necessarily all experience the same emotional response. Gruskin’s studies have examined this through the lens of genetics, looking at the emotional responses generated by movies in unrelated people, fraternal twins, and identical twins. What he found was that identical twins had much more similar processing mechanisms—the same areas of their brain would light up under the fMRI scans—than fraternal twins, who in turn had more in common with each other than unrelated people did. This suggests that genetics plays an important role, and that brain responses to movies are actually heritable by up to 20%. While everyone is working with the same base neural framework—since our sensory processing areas are so crucial to our survival, they tend to be fairly standardized across all members of the species—our multisensory processing areas can vary more, and, on top of that, our frontal lobes are often completely different from one person to another. And while environmental factors have to be considered as well, Gruskin confirmed that genetics play a clear role in our emotional responses to movies.

Moving back to music, we explored how different compositional tools can evoke different emotions or narratives. We looked at a monochromatic drawing of a path through a forest (a photograph Green took of a piece currently on display at the Whitney) as Green improvised on the piano. The music started off light-hearted, shifted to a more ominous, suspicious tone, then returned to the more melodic, whimsical melody of the beginning. The responses to the art, or the stories people imagined taking place in it, reflected similar moods; one audience member said she pictured herself skipping through the forest, getting lost, then finding her way again, a sentiment echoed by many others. Music, we found, has the unique power to suggest movement, or story, in what’s otherwise a completely static image. It reminded me of ballet; while there are no words, the combination of pantomime and music can still create a clear dialogue. In some cases, the movement can even be superfluous; just think of Peter and the Wolf, a completely wordless, yet still highly narrative, piece of music. There are certain patterns, Green mentioned, that are often associated with certain types of emotions or scenes; for example, the whole tone scale is often used in dream sequences. But, as Gruskin brought up, that may be a cultural influence (we’ve been conditioned to associate the whole tone scale with a dream setting, as a result of seeing the two linked together so often) and not a direct evocation.

The night ended with a brief closing performance from Green, an original song she’d written called “Corner of my Dreams.” It was a light, lilting, smooth jazz kind of love song, the perfect way to end an evening full of stories, music, and science.

Event images via Lorelei Gorton.

0 Comments

0 Comments