Second half of Art Humanities bringing you down? Look no further than this compiled timeline of all of the works from the second half of the semester.

I don’t claim to be an expert–in fact, I am not one. My Art Humanities Professor, on the other hand, is an expert. This timeline attempts to be as true to her words as possible, though please don’t get mad if anything is off. If you are looking for anything from the first semester, check out my old post.

Mid-Semester Work

Zeuxis Choosing His Models For His Painting of Helen of Troy, Angelica Kauffman

This oil-on-canvas Neoclassical painting looks back to the Renaissance, utilizing idealized naturalism with a theatrical flair as the dramatic drapery from the shoulders, idealized poses, and a central figure in white. The central figure is a woman in white getting measured, surrounded by individuals who interact with her gaze and gesture. Calipers ae placed in the foreground of the image, keeping consistent with a theme of measurement and artistic judgement, while a woman on the right lifts a paintbrush, serving as a potential insertion of Kauffman as a model and a painter. This is believed to be the first time a woman is exhibiting agency within a painting. Rather than present Helen as a single, beautiful individual, Zeuxis chooses to portray Helen as a culmination of many models, deconstructing and reconstructing beauty. The form is classic and idealized.

Designs, Angelica Kauffman

This oil-on-canvas Neoclassical piece looks back to the Renaissance with its use of idealized naturalism and the portrayal of a woman studying a statue to understand the shape of a man. While Kauffman and many other woman could not obtain a formal education at the academy, women were able to look to the Classical past for inspiration on the male figure. This is not a self-portrait, but rather embodies the creative experience of making something complex and intricate. This was a painting in a series of four commissioned by the Royal Academy, encompassing the elements of art: Invention, Composition, Design, and Color. This is an allegory of design, not on display but a professional of it.

The Oath of Horatii, Jacques-Louis David

This large, Neoclassical, oil-on-canvas, historical painting looks to the Classical past, more specifically ancient Rome, to depict a singular, heroic moment in history. Commissioned just before the French Revolution, the work holds major historical significance as it embodies Enlightenment ideals of civic duty, sacrifice, and being willing to die for your ideas, which strongly resonated in the late 18th century. The composition is stark and detailed, with a theatrical theme as three brothers reach toward their father’s swords in a symmetrical manner. The use of linear perspective and chiaroscuro directs the viewer to this act, while the figures’ bold outlines and sharp musculature reflect the classical form. In contrast, the women and children are grouped together in a slumped manner to appear grieving, reinforcing ideas of sacrifice at a cost. The grouped nature of the painting creates a tension of public duty and private loss. The theme of heroism is evident through the sharp, bold, and dramatic scene that is extremely theatrical, formal, and upright. This is a flip from the classical sculptures we have seen before and is rather in portrait. The classical bodies utilize wet drapery, but instead of embracing the full heroic nude, the soldiers stand with clothing. Dynamics imply energy and inflection of movement.

The Family of Carlos IV, Francisco Goya

The post-French Revolution oil-on-canvas painting straddles between the Enlightenment and the Romantic period. It rejects a perfectly staged, frontal composition commonly seen in portraits of the past, but rather is a sort of un-idealized naturalism. They are not majestic, rather our figures are pudgy, wrinkly, and lack a focal point. The hierarchy is confusing and it lacks the formality associated with a group portrait of the monarchy. Also, Goya sneaks himself into the painting. As this is Post-French Revolution, monarchs didn’t want to portray themselves as opulent and wanted to seem relatable, ordinary, and human. Its loose, textured form reinforces this content, rejecting idealization in favor of a candid, almost subversive realism. The moments had to look normal. Brushstrokes build the texture and the color of the painting while the use of chiascuro casts shadows over the figures.

Second of May, Francisco Goya

This oil-on-canvas piece comes just from the end of the Enlightenment period and into the Romantic Era. The subject is the brutality, pointlessness, and futility of war. There is a rejection of the beautification associated with war and an embrace of brutalization. Set during the Spanish resistance to Napoleon’s occupation, the painting captures the raw brutality of street combat as armed-with-sticks Spanish civilians fight against French Mamluk soldiers. The image is crowded, unbalanced, and dynamic. There is no one focal point, just flailing limbs, raised weapons, and tangled bodies. The Mamluks, identifiable by their turbans, firearms, and curved swords, and the Spaniards, with makeshift weapons are tossed in loose , less refined brushwork. There is an energetic nature, in motion, with arms gripping around a man’s waist to pull him off the horse.

Third of May, Francisco Goya

This oil-on-canvas painting follows the Second of May painting by Goya. There is a clear division of the figures depicted. It depicts the execution of Spanish civilians by French soldiers during the war. Goya humanizes the Spaniards by displaying their faces and their stoicism as they stand before the firing squad. The composition is sharply divided: the Spaniards, on the left, are lit and individualized, while the French, on the right, are mechanical and faceless. The focal point is a man in a white shirt, arms stretched out in a crucifixion-like pose, his palms marked by stigmata-like wounds. This martyred figure is illuminated by a lantern at the center of the composition, casting a harsh light across the scene. The blood-soaked ground and surrounding corpses, paired with the dramatic chiascuro and visible brushwork, heighten the emotional intensity while subverting traditional heroic narratives. The viewer is positioned slightly behind the firing squad, complicit and a witness to the act.

Luncheon on the Grass, Édouard Manet

This Impressionist piece starts the embrace of painterly art. Rejected by the Salon, the painting scandalized contemporary audiences by placing a nude woman–modeled with the realism of a portrait–among fully clothed men in a park. While traditional art had long depicted the nude, Manet’s figure is not mythologized or idealized; she stares directly at the viewer, breaking the passive female archetype and asserting a confrontational present. Her clothes lie discarded beside her. Instead of the traditional perspective and depth, the painting uses flatness, angular forms, and visible brushstrokes. The lighting is uneven, and shadows collide in haphazard ways, and trees collide together, no longer soft and diffused. The use of harsh blacks is a hallmark of Manet’s style.

Olympia, Édouard Manet

This oil-on-canvas Impressionist painting depicts a nude woman lying on plush, white bedding. Unlike Aacdemic nudes that idealized the female body through soft modeling and mythological distance, Olympia is un-idealized, flat, and angular, her body outlined against the white bedding with minimal shading or depth. She stares directly at the viewer. Identified as a sex worker through the flower in her hair and her black ribbon around her neck, the viewer is the implied client. A Black maid presents her with a bouquet, likely from a client, and stands behind Olympia in a role of servitude. The contrast between Olympia’s pale skin and the maid’s dark complexion is evident. Historically, this may be one of the first depictions of a Black woman in paintings. The painting also played with ideas of French vs non-French since Black women were not considered French at the time. The painting was controversial, not only because of the subject, but for its style–the visible brushwork, lack of modeling, and refusal of illusionist broke from Academic standards. The lighting plays with the focal point.

Portrait of Laur, Édouard Manet

The oil-on-canvas Impressionist piece depicts Laure, a Black model whom Manet also used in his other painting, Olympia. She serves as the sole subject of this portrait. This work departs from the Academic traditions of idealization, depth, and strong contrast. Instead, Manet uses loose brushwork, a flattened perspective, and a limited, dark color palette to emphasize the painting’s painterly quality. Laure is in a white dress, rendered with wide, gestural strokes, her gaze directed off to the side, never meeting the viewer. The painting’s historical significance lies in how it complicates 19th-century conceptions of Frenchness and visibility. Laure–a Black woman in Paris–is both part of and apart from the national identity. Once more are the ideas of. The darkness is indicative of Manet’s style.

Mother and Sister of the Artist, Berthe Morisot

This oil-on-canvas Impressionist piece is defined by the loose brushstrokes and painterly quality. By leaning into the ideas of luminosity, there is a rejection of the linear perspective and idealization. Instead, Morisot captures an everyday interior scene, split between the left side, filled with life and a blank stare of Morisot’s sister, and the right, shadowed and subdued, occupied by her mother reading. The spatial division accentuates the themes of life and death. Light floods the scene, casting reflections in the mirror, and illuminating the figures with a soft naturalism, especially in details such as the translucent face. The figures do not perform for the viewer; they simply exist, embodying a non-idealized view of womanhood and domestic life. Historically, the painting is significant for offering a rare female perspective within the Impressionist movement and for asserting the value of the feminine experience. Manet drew the black onto the mother, which Morisot did not favor. The translucence of the vase is faced with naturalism. There is also the conceit of the artist in a self-portrait that is less obvious.

The Cradle, Berthe Morisot

This Impressionist oil-on-canvas work quietly disrupts traditional depictions of motherhood by rejecting the idealized Madonna and Child motif. Instead of a spiritual or sentimental bond, Morisot depicts a weary, disconnected mother who gazes at her sleeping infant with a tired, ambivalent look. Her dark clothing, hand propped against her face, and a slightly discheveled appearance evoke emotional and physical exhaustion. The veil-like cloth, soft yet ever-present, divides the compositions and creates a physical barrier between the mother and child. The baby’s pose mirrors the mother’s bent arm, reinforcing their connetion while emphasizing their difference. The soft, loose brushwork reminiscent of Impressioinism heights the tactile quality of the scene, offering a raw, unidealized portrayal of womanhood and domestic life. This is a female artist working in a male-dominated space and the artist plays with the corporality.

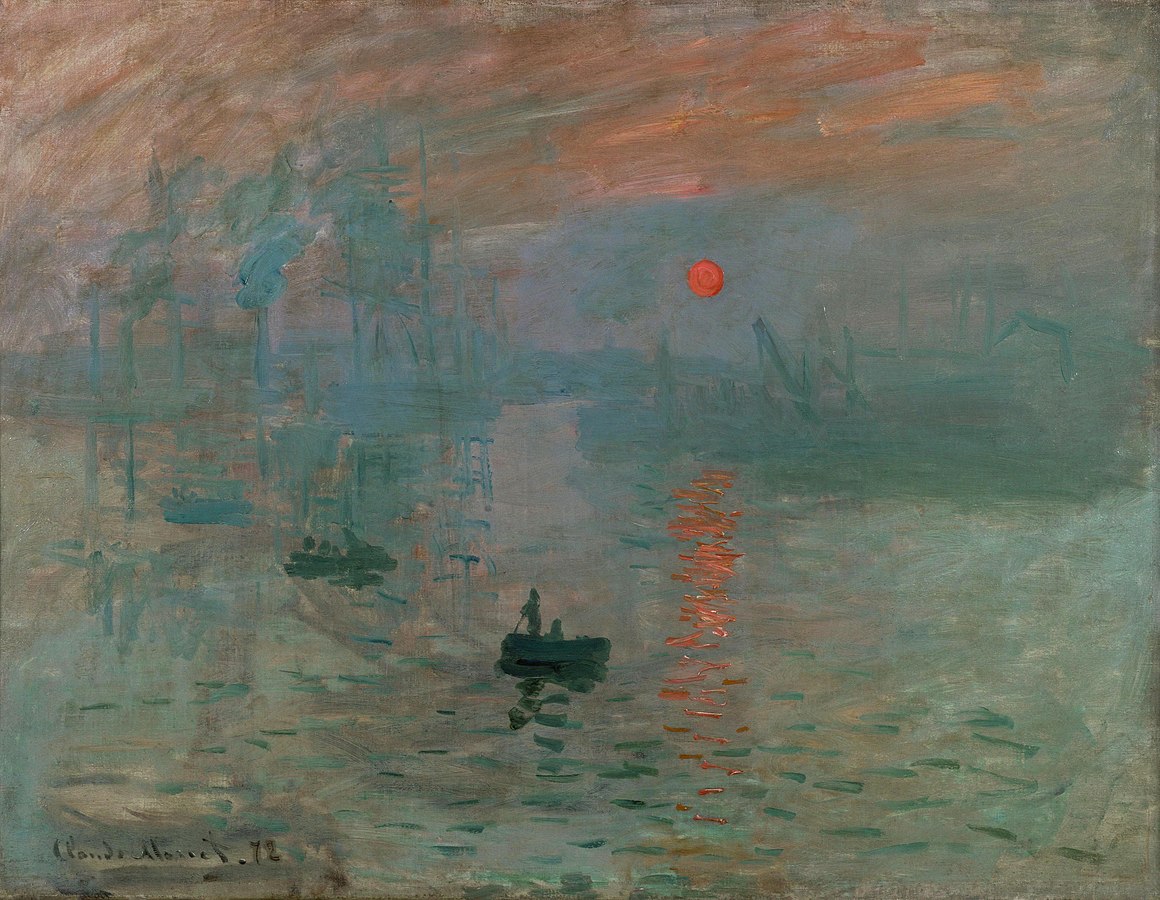

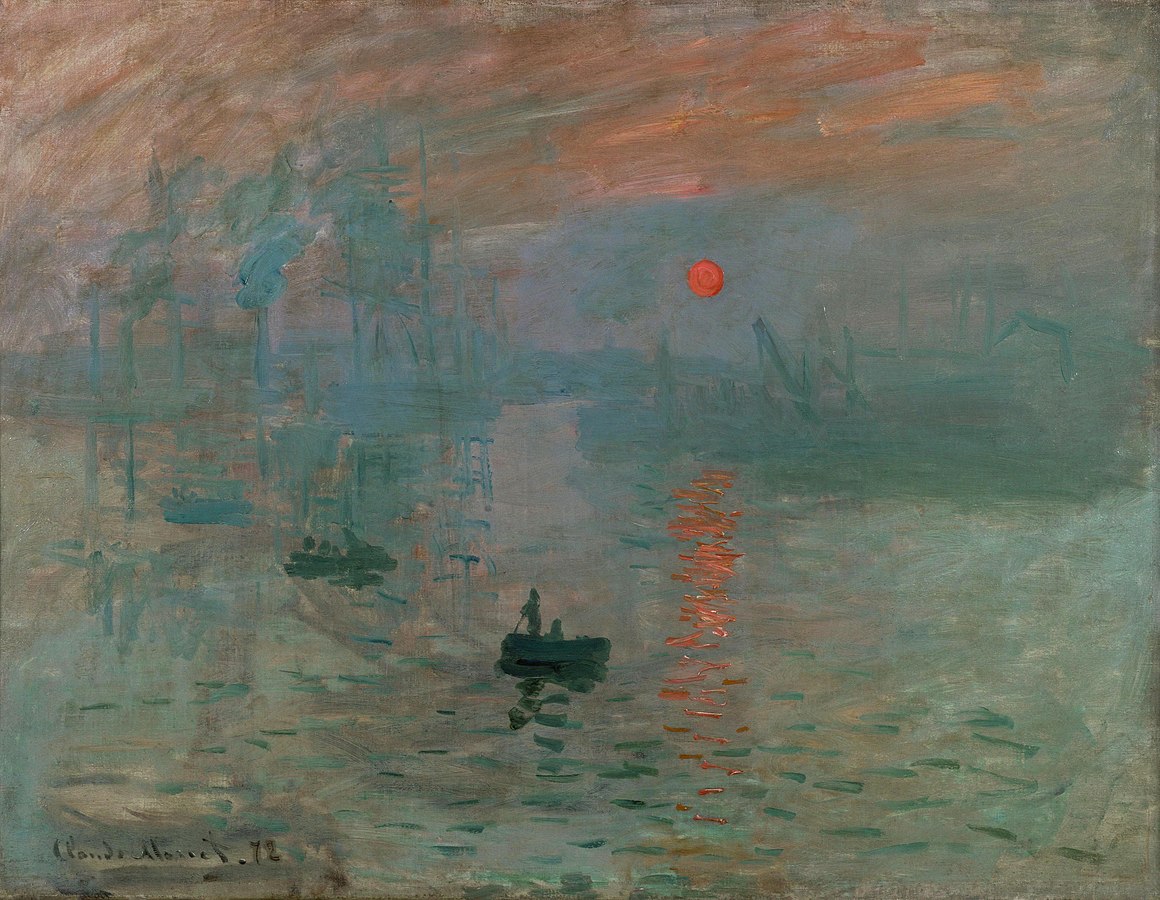

Impressions (Sunrise), Claude Monet

An oil-on-canvas Impressionist painting highlights light, atmospheric conditions, and luminosity. Monet departs from acaemic traditions of strong contrast, 3D perspective, and the rejection of the painterly quality. Instead, Monet focuses on light and embraces plein-air painting, made possible by the invention of portable paint tubes, and its engagement with themes of modernity and industrialization through atmospheric conditions. Monet’s short, segmented brushstrokes and loose, painterly surface reject the clean contours and depth of Academic art, instead capturing the ephemerality of a single moment in time. Shadows are rendered not in black or gray, but in rich blues, contributing to a luminous palette that heightens the emotional and sensory effect of the image and allows individuals to see the scene as they would remember it. Rather than mixing the colors, Monet utilizes impasto to mimic the fleeting nature of visual perception. The subject is not a static object but the quality of light.

In the Lodge (At the Opera), Mary Cassatt

This Impressionist painting utilizes dark, rich hues to depict a woman being watched. With the use of swabs of loose, expressive brushwork, the piece departs from the polished realism of Academic art and instead embraces the painterly qualities typical of Impressionism. The subject is a woman sitting in an opera box, holding binoculars, gazing into the audience. Yet, across the canvas, a man watches her, establishing a dynamic of observation and moving the painting into a commentary of public spectatorship. While the woman occupies a public space, she is also rendered vulnerable to being watched. The brushwork contributes to this tension of the watcher versus the watched, wherein the soft brushstrokes blur the outlines of the other individuals.

Stacks of Wheat (End of Summer), Claude Monet

Monet creates a collection of 25 oil-on-canvas paintings exemplifying Impressionism to capture the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. Departing from academic traditions of sharp contrast, linear perspective, and polished finish, Monet embraces painterliness through loose brushwork, impasto, and minimal color blending. The haystacks themselves are not the true subjects, rather they serve as conduits to study the changing qualities of light, time of day, and season. Shadows are rendered in blues and darker tones of the original colors rather than black, reflecting how the human eye perceives light and shadows. Made in plen-air, each canvas captures a specific moment, emphasizing temporality and the impermanence of the visual expreience. Though the compositional structure remains consistent across the series, the surface textures and colors vary, distinct in material expression. This series helped redefined the purpose of a painting, not defining single objects but time itself.

Rouen Cathedral series, Claude Monet

Monet’s Impressionist series of paintings focus on the atmosphere of the Gothic Rouen Cathedral as the backdrop for the subject. Painting en plen-air, made possible by the invention of paint tubes, allowed Monet to capture the cathedral at different times of the day under varying weather conditions. The subject is not the cathedral but light: the transient reflections, shadows, and tones. Utilizing short, quick brushtrokes, Monet depicts a field of color and transforms art from the subject of objects to the subject of temporality and light.

Martin House, Frank Lloyd Wright

This Prarie-style house reflects a distinct version of architecture inspired by Japanese prints and rooted in harmony with the natural environment. Built on an expansive flat land, the home emphasizes horizontality thorugh low, ground-hugging proportions, extended rooflines, and bands of “ribbon” windows. Roman bricks and natural materials reinforce this horizontal emphasis, blending the structure into the landscape. The asymmetrical layout and cruciform floor plan breaks away from the rigid geometries of traditional Western archtecture. The entrance is concealed behind high walls, prioritzing privacy and reinforcing the idea of the home as a sanctuary. Light is carefully controlled throughout the house through strategic window placement and careful control of the inner light sources. Frank Lloyd Wright designed the insides of this home.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon, Pablo Picasso

This Protocubism piece depicts five fragmented nude sex workers. The figures’ distored, angular bodies and mask-like faces–some inspired by Afircan art–offer a flattened and abstracted form of sex workers. The inclusion of African and Latin American and Pacific Island influences raise important questions about cultural appropriation and the racialized gaze, especially in the context of colonialism and the sexual depiction of the female subject. The painting’s massive scale and disjointed composition lacks spatial continuity and emotional connection between figures, which deny any passive, nay pleasurable viewing experiences. The viewer is positioned as the potential client, confronting a grotesque and hypersexualized scene that resists beauty and coherence. The women are shaded, distorted, and broken into a part.

Guitar, Pablo Picasso

Picasso leans into Cubism in this cardboard guitar and sheet metal sculpture. Deprating from the tradition of carved marble or cast bronze, Picasso embraced ordinary, industrial materials that he challenged the hierarchy of “high” art with. The abstract work deconstructs the guitar into flat planes, geometric shapes, and inverts positive and negative spacces. Influenced by African Kru masks, the piece incorporates elements of African art, though many believe this is cultural appropriation. While its simplified forms may appear playful or even “childish,” this piece leans into non-impressionism and reconstructures a traditional representation of art.

Guernica, Pablo Picasso

This oil-on-canvas painting inspired by Cubism is a post-war documentary painting. Inspired by the horrors of massive air raid ordered by Francisco Franco over the Basque town of Guernica, Picasso fragments and distorts human and animal bodies to communicate the trauma of war. The composition is chaotic and collapsed, filled with gaping mouths, contorted limbs, and angular shapes emphasizing fear and helplessness. Although resembling a collage, this is, in fact, a painting, allowing the multiple figures to experience a collective horror. Rendered entirely in black, white, and gray, the color reinforces the bleakness and brutality of the event and heightens the emotional investment. This is historically an anti-war statement.

Sacrifice, Romare Bearden

This collage was inspired by Picasso’s Cubism and builds on his legacy by using fragmented, geometric forms to create a figural composition. In this work, the artist creates a moment of horror through a flattened plain and cohesive disjuntion. Drawing from the Northern Renaissance, particularly the drama and shadow of Caravaggio’s Sacrifice of Isaac, Bearden also synthesizes influences from Mexican muralists like Orozco and Rivera, Chinese calligraphy, and African art to develop a uniquely modern and diasporic visual language. His choice of cheap, everyday collage materials raise questions about artistic legitiamcy and who gets access to or is able to define “high” art? While Picasso appropriated African masks for formal experimentation, Bearden’s work attempts a reintegration, using African visual traditions to connect and build African Amerian identity rather than abstract or distance it. The fragemented forms and flattened space reflect a moment of endurance.

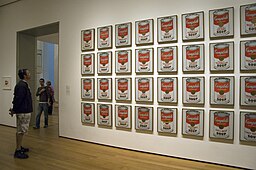

32 Campbell’s Soup Cans, Andy Warhol

Utilizing Pop Art, Warhol critiques the commodification of domestic life and offers a satirical commentary on post-war consumerism. By employing mechanical processes such as stencils, silkscreen printing, and projects, he deliberately removes the hand of the artist, echoing the classical debate over whether the artist is the executor or the conceptual mastermind. The image, repeated with minimal variation, reflects mass production and seriality, mirroring the logic of consumer goods in a capitalist economy. While the piece is displayed in fine art contexts, its subject matter and style reflect commercial imagery, challenging the boundary between high and low art. Warhol appropriates intellectual and represents them with a heightened contrast and aesthetic flattening, suggesting the loss of uniqueness. Repetition leads to a culture of mass production.

Marilyn Diptych, Andy Warhol

Utilizing Pop Art, Warhol creates a diptych critiqueing the mass production and commodification of celebrity culture through the image of Marilyn Monroe. By using silkscreen printing, Warhol removes the hand of the artists, raising questions about authorship and originality in art. The work juxtaposes high and low art: it is presented as fine art, yet mimics advertising and mass-produced imagery. Warhol appropriated Monroe’s likeness, an image already circulating in society, and multiplies it across two panels–one brightly colored and the other faded and degraded. This serial repietition mirrors the overconsumption of her image and reflects the hyper-exploitation of her identity–turning her into a caricature. The diptych format evokes religious altarpieces, suggesting a secular canonization of a Hollywood figure. Raised Catholic, Waarhol draws on the visual language and exposes the artificiality and grotesque excess of celebrity worship. The work’s garish palette, non-idealized flattening, and smudged imperfections strip Monroe of individual humanity, replacing her with a mass-produced icon. Its form–mechanically repeated, fading, and exaggerated–mirrors its content. She is a consumable image.

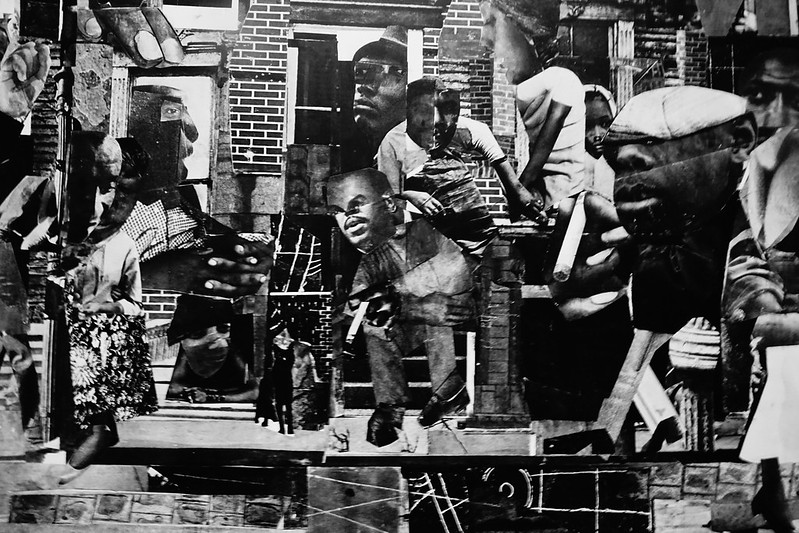

Prevalence of Ritual: Baptism, Romare Bearden

This collage explores the tension between fragmentation and narrative coherence, drawing on inspirations of the North Carolinian Spring Sunday baptisms. Though constructed from disjointed and disproportionate body parts, the work weaves together a unified story through visual symbolism and cultural reference. Using collage as a formal and conceptual mask–echoing African art traditions–Bearden integrates materials from magazines, art history textbooks, and documentary photography to depict the layered realities of Black life in America. The flattened composition resists spatial depth, instead presenting a compressed field. The train in the background suggests both a personal migration and a collective journey. The absence of a single focal figure mirrors the communal nature of the baptism and destabilizes traditional hierarchies in art. A female figure, adorned with a Congo mask and African water spirit, is representative of Bearden’s connection to African art and its integration with African American traditions. The form–cut, layered, and assembled– was inspired by Documentary photography and plays with the idea of who gets to author or inhabit a space.

The Dove, Romare Bearden

Bearden plays with fragmentation and synthesis to depict the vibrancy of the everyday Black life in an urban setting. His collage captures the moments of community–people smoking, chatting, and a dove perched on a windowsill. These scenes reflect both the mundane and the deeply connected. Though visually disjointed, through layered paper cuts and disproportionate forms, the composition unifies into a cohesive whole that evoke the energy and intimacy of collective life. Bearden merges low art materials with references to high art structures, drawing inspiration from artists such as Piet Mondrian. The presence of the dove, a specific and recognizable urban bird, bridges the particular with the universal, symbolizing both the ordinary and the idea of peace.

Thirteen Most Wanted Men at New York’s World Fair, Andy Warhol

This Pop Art piece embraces the aesthetics of mass production, transience, and commercial culture using serial repetition to question originality and the commodification of identity. Warhol removes the artist’s hand through his mass produced through silkscreen printing, producing a grid of mugshots that flattens individuality and turns the infamous into consumable imagery. By appropriating and recirculating intellectual property–here, images of criminals–Warhol blurs the lines between celebrity and infamy and challenges the viewer to consider how both are manufactured and consumed. The black, high contrast compositions dehumanize the subjects, stripping them of narrative context and reducing them to visual archetypes. Juxtaposing high and low art, Warhol elevates mugshots into the fine art sphere, provoking the concern of the glorification of crime. The positioning of men facing one another introduces a subtle tension, suggesting themes of desire with possible homosexual undertones. This piece was not well received and was painted over to hide it from the public.

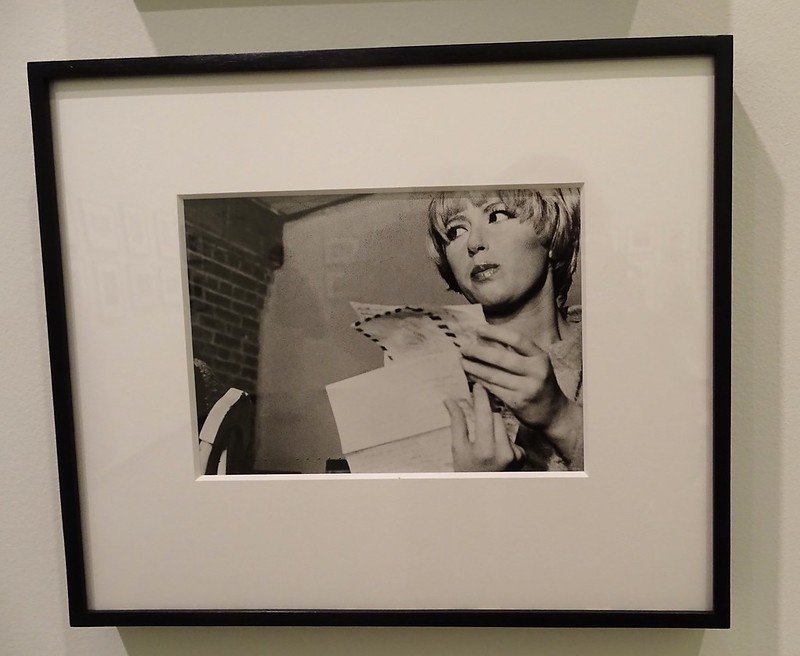

Untitled Film Stills, Cindy Sherman

These series of photographs feature Cindy Sherman herself, yet they are not self-portraits in the traditional sense. Instead, they serve as constructed representations of what it means to “be” a woman in media, culture, and visual history. Through adopting stereotypical female roles–such as the ingenue, housewife, or femme fatale–Sherman interrogates how femininity is staged, performed, and consumed. The photographs are carefully composed to appear spontaneous and natural, playing on the assumed authenticity of photography as a medium. Crucially, the gaze becomes central. The works reject the passive framing of the male gaze and assert a female-centered point of view, questioning who is looking, who is being looked at, and why. The series utilizes seriality to expose the narratives of women in art.

Untitled (Maid from Olympia), Jean-Michel Basquiat

This Neo-Expressionist painting reimagines the maid from Manet’s Olympia, centering her as the primary subject and confronting the viewer as the implied client, invoking themes of voyeurism and the politics of the gaze. Referencing Manet both visually and textually, the work pulls back the metaphorical curtain, exposing not just the subject but the act of looking itself. In contrast to Manet’s composition, where the Black maid is marginalized as a background figure, this painting gives her scale, centrality, and agency. Rendered in bold, abstracted strokes, the figure asserts her presence. The graffiti-like nature, though notably NOT graffiti, is an important aspect of this painting. Black and red dominate the body of the maid and the stark white background allows her to be the central figure. Her blackness is neither erased nor aestheticized, but made visible and unignorable. Circulating around the image are layered questions of authorship and appropriation.

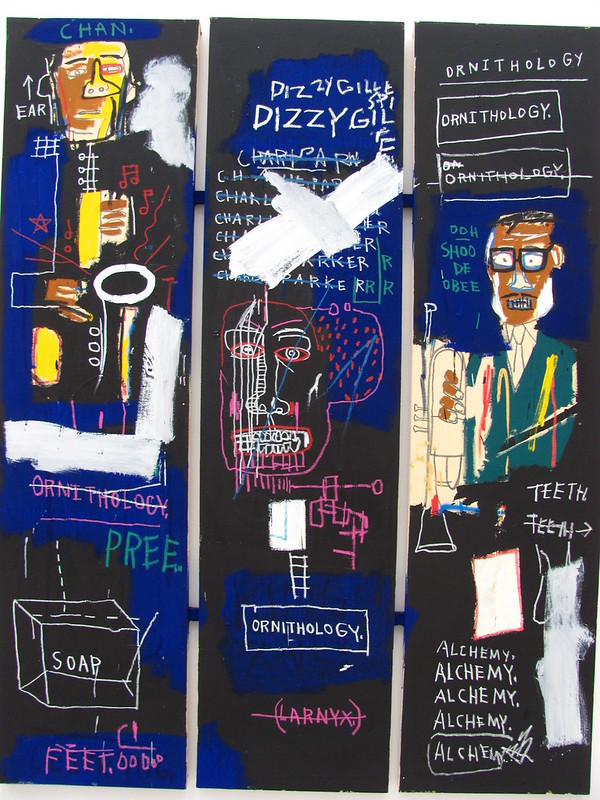

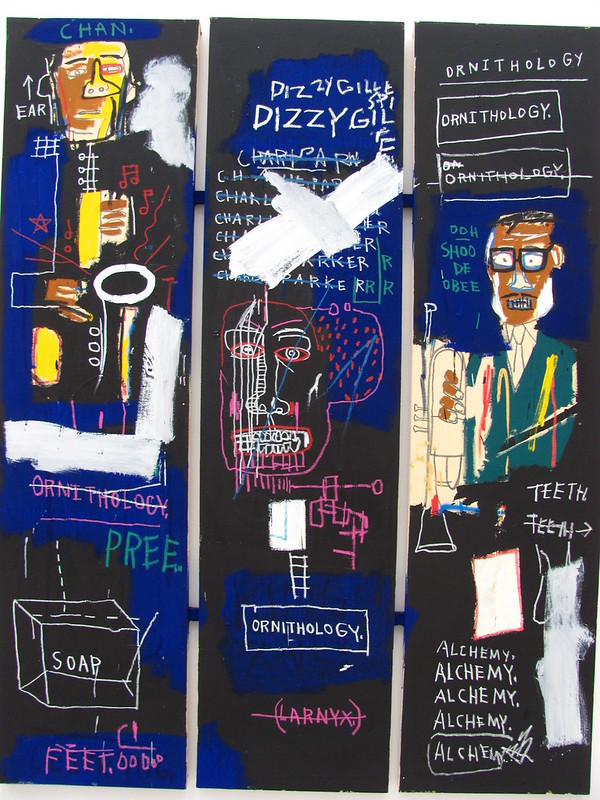

Horn Players, Jean-Michel Basquiat

This acrylic and oilstick triptych, grounded in Neo-Expressionism, honors the legacy of jazz legends Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie and reasserts the transformative power of African American music. Though the triptych format traditionally evokes medieval religious altarpieces–three panels with a cohesive narrative–Basquiat instead fuses them into one single, chaotic composition. The piece juxtaposes high and low art: its monumental scale and art-historical format signify reverence, while the graffiti-like text and gestural linework are associated with “lower” forms of art. Notably, Basquiat rejected the label of his work as graffiti. The inclusion of song titles such as Orinthology reinforces the auditory sensoriality of the piece, while the scribbled text, fragmented forms, and disproportionate bodies mimic the improvisational nature of jazz. Yellow highlights illuminate the figures against a dark ground, drawing from chiaroscuro to emphasize contrast and fragility. Through repetition, abstraction, and stylized distortion, Basquiat infuses spontaneity and energy into the canvas, reintroducing the idea of the “hand of the artist” in a deliberate break from Pop Art’s mechanical detachment.

Grillo, Jean-Michel Basquiat

This Neo-Expressionist four-panel series, composed of acrylic, nails on wood, vinyl, oil, and collage, draws from diasporic traditions to explore themes of inheritance, memory, and spiritual continuity. The assemblage of everyday materials challenges the hierarchy of “high” art, while the layered compositions reference African cosmologies, Afro-Caribbean ritual, and oral traditions. These panels are visually and materially dense, invoking the Nkisi Nkondi figures, sculptures embedded with nails used to guide ancestral spirits. These culturally encoded symbols link the panels to the idea of Griot as a memory and oral tradition in African and Afro-Caribbean societies. In fact, the name “Grillo” is derived from the word griot. The figures in the panels evoke African tribal masks and Caribbean Voodoo iconography to create a version of diasporic identity.

Untitled (Studio), Kerry James Marshall

Marshall’s piece, acrylic-on-PVC-panels, presents a modernist imagining of the artist’s studio, centering Black figures as both the creators and the muses in the composition. Marshall depicts a modernist take and presents an idealized and meticously composed artist’s studio.The painting blends techniques across Western art history–naturalistic modeling, painterly brushstrokes, abstract flatness of Pop Art, and impasto–while deliberately using a bold and symbolic color palette. Most notable is the deep, unmodulated black used for the figures, a visual strategy that affirms Blackness without ambiguity or compromise. Rather than opting for naturalistic skin tones, Marshall uses black as a powerful, declarative presence. A standing figure in the back evokes classical contrapposto, referencing idealized naturalism, while a still life on the table nods to the Flemish painter Clara Peeters. The interplay of light and space recalls Vermeer’s use of luminosity, and the abstract painting on the easel, with impasto and drips, alludes to Pollock’s abstraction. On the left, the composition flattens, yet on the right, it deepens with the reversal of the illusion of depth. The work’s monumental scale furthers its impact, asserting that Black subjects and Black art belong and deserve to be a part of art.

End of Class

The second half of the class requires us to think about the artists we are given and to identify another work like these artists. As such, I am listing out key words that I believe best represent each artist’s work, as well as reminding us of the compiled works belonging to each of them.

- Angelica Kauffman: Neoclassical, Depictions of Women, Idealized Naturalism

- Zeuxis Choosing His Models for His Painting Helen of Troy (1775-1780)

- Designs (1778-1780)

- Jacques-Louis David: Neoclassical, Historical Painting, Civic Duty

- The Oath of Horatii (1785)

- Francisco Goya: Raw Depictions, Loose Brushstrokes, Chiascuro

- The Family of Carlos IV (1801)

- Second of May (1808-1814)

- Third of May (1808-1814)

- Édouard Manet: Impressionism, Use of Dark Colors, Loose Brushstrokes, Flatness

- Luncheon on the Grass (1862-1863)

- Olympia (1863)

- Portrait of Laure (1863)

- Berthe Morisot: Impressionism, Everydy Domestic Life (Namely Women), Loose Brushstrokes

- Mother and Sister of the Artist (1869-1870)

- The Cradle (1872)

- Claude Monet: Impressionism, Atmospheric Conditions, Light, Temporality, Plen-Air

- Impressions (Sunrise) (1872)

- Stacks of Wheat (End of Summer) (1890-1891)

- Rouen Cathedral Series (1894)

- Mary Cassatt: Impressionism, Use of Dark Colors, Women in Public Spaces

- In the Lodge (At the Opera) (1878)

- Frank Lloyd Wright: Prarie Style, Insistence on Horizontality, Integration with Environment

- Pablo Picasso: Cubism, Fragmentation, Inspired by African Art, High versus Low Art

- Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907)

- Guitar (1912)

- Guernica (1937)

- Romare Bearden: Collage, African Art integrated with African American Identity, Fragmentation versus Synthesis, Everyday Materials

- Sacrifice (1941)

- Prevalence of Ritual: Baptism (1964)

- The Dove (1964)

- Andy Warhol: Pop Art, Seriality, Repetition, Commodification, Loses Hand of the Artist, High versus Low Art

- 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962)

- Marilyn Diptych (1962)

- Thirteen Most Wanted Men at New York’s World Fair (1964)

- Cindy Sherman: Photography, Depictions of Females through Female Gaze, Women in Media and Culture

- Untitled Film Stills (1977-1980)

- Jean-Michel Basquiat: Neo-Expressionism, Sketch-like, Hand of the Artist, Bold Colors, Inspired by Western Art and African Art

- Untitled (Maid from Olympia) (1982)

- Horn Players (1983)

- Grillo (1984)

- Kerry James Marshall: Modernism, Use of a Variety of Techniques, Painterly, Bold Colors such as Deep Black and Red

And that’s it folks! Wish me and many others luck!

Zeuxis Choosing His Models for Helen of Troy via ItOldYa420, The Oath of Horatii via Wikimedia Commons, The Family of Carlos IV via IToldYa420, Second of May via Wikimedia Commons, Third of May via Wikimedia Commons, Luncheon on the Grass via Wikimedia Commons, Olympia via Wikimedia Commons, Portrait of Laur via Wikimedia Commons, Mother and Sister of the Arist via Wikimedia Commons, The Cradle via Wikimedia Commons, Impressions (Sunrise) via Wikimedia Commons, Stacks of Wheat (End of Summer) via Wikimedia Commons, Martin House via Wikimedia Commons, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon via Flickr, Guitar via Flickr, Guernica via Wikimedia Commons, 32 Campbell’s Soup Cans via Wikimedia Commons, Marilyn Diptych via Flickr , The Dove via Flickr, Horn Players via Flickr, Untitled Film Stills, Cindy Sherman via Flickr

0 Comments

0 Comments