Students of Columbia’s Sound Art MFA program presented installations in the Music and Arts Library. Staff Writer Celia Bernhardt learns what sound art is and describes a few beautiful pieces from the show.

On the dark, windy evening of October 29, the Music and Arts library hosted this year’s “Sound Art in the Library” show, featuring works from students in the Sound Art MFA program at Columbia.

Quite honestly, I needed to Google what sound art was on my walk there; I learned that it was simply art using sound as its primary medium. This seemed reasonable enough.

Thinking, for some reason, that this was a one-by-one presentation of work in front of a sitting audience, I arrived promptly at 6:00 PM. This proved to be relatively early for the nature of the event, which was actually a walk-around-and-look-at-things kind of show. Not many visitors had arrived yet. One older man saw my confusion and welcomed me. I asked where the sound art was — he responded, “It’s all over!” and told me different projects were in different locations throughout the library. At this point, I didn’t know there was a printed list of the project locations, so I began the night by wandering around, bewildered.

The first piece I stumbled into was called Abstract Meditation #2, by Gladstone Butler. In a small, dark room, visitors were enveloped in mystical lighting and strange music. Two lights pulsed from opposite walls, filling the room with an indigo glow, while speakers sat in all four corners playing the soundtrack.

Now begins the part of this article where I attempt to do what I’ve always avoided—describing sound in words beyond “so cool.”

The music filling up this room included some deep, rumbling, clean sounds reminiscent of the sound effects you might hear in a movie or planetarium when a planet, spaceship, or UFO glides past the screen. There were clinking, sparkly sounds like glass against glass sprinkled throughout the score, and electric guitar playing up and down a minor, jazzy scale. The music was just dissonant enough to feel mysterious and a little ominous, but never enough to feel disturbing or push you out of the room; it was even comforting, in a way. The other visitors and I fell into a pattern of stopping by the speaker in each corner, then simultaneously rotating around to the next one when someone stepped forward.

Leaving this womb of sorts after a few minutes, I resumed the search for installations. A couple more patrons were trickling in now. The next piece was called Something About… a Process? It was created by Anthony Sertel Dean, and consisted of two computers playing different videos and sound (through headphones—a good move in a library that was starting to fill up with the competing sounds of everyone’s projects and soft chatter.) The first of this series pictured a hand writing and tracing over a confusing, emotional message in an excruciatingly slow manner. (This is a compliment, I think. Art is supposed to make you feel weird sometimes, and this succeeded.) Some words were gigantic, while others shrank too small to read. The sound accompanying it was an overwhelming staticky drone, intense and full, playing a chord that I couldn’t fully understand.

The other computer played a video of two hands interacting with a lightbulb. The hands seemed to alternate fighting and comforting one another, inching towards and orbiting around the light with awe, without touching it. I have trouble remembering the accompanying sound, but I think it was more clear and melodic than the previous, conveying emotions I could more easily grasp. These pieces were beautiful in their narration, and their ability to convey raw, intense emotions.

Resurfacing, I took off the headphones and followed a sound emanating from one end of the library. Turning around at the loudest point, I found its source—Untitled (Cones) by Merry Sun, in an aisle between two bookshelves. Two traffic cones were arranged to lay on their side haphazardly with the hollow bottoms facing one another, connected to each other through audio tapes running between them. Sounds of harsh wind, static, and low notes accompanied the cones. This piece took me aback in its ability to convey a relationship between the objects and sounds used. My brain processed the sound as something coming from whatever was happening between these two cones; they became living beings capable of producing noise and processes. What was happening to them in this stretched-apart state? What was going on in the tapes running between them?

Walking through to the other side of the aisle, another installation awaited. This one was titled Beyond February (The Periodic Table of Black Revolutionaries), created by Char Jeré, and was strikingly beautiful. Center stage against the back wall of a small room was a large periodic table—designed just as it typically would be, but with elements that were, instead of metals, the names of “elemental” Black women and queer people throughout history. The piece was lit up with multicolored lights which switched their hues back and forth. Pleasant buzzing emanated from the room, which had pipes of different shapes and sizes sprouting out of the floor, multiple amps, a red light shining up onto the periodic table, a book, and some other electronics. On a tablecloth-adorned shelf, more books and objects were set up, each touching or leaning on another—hot combs, a well-worn Autobiography of Malcolm X, wires wrapped around more metal pipes, Baracoon by Zora Neale Hurston, and more.

This being such a breathtaking, complex piece, I wished I could have heard from the artist; this was the greatest loss in my arriving and leaving early. One person who seemed to be overseeing the exhibitions told me that many of the artists were taking a breather elsewhere for the first hour or so, after setting up their pieces. He told me Jeré described themself as an Afro-Fractalist (branching from the term Afro-Futurist.) I stood by Beyond February for a long time.

The next piece I had to really hunt for. It was titled Study for Membrane (from The Productive Secretion of Residence), by Jonathan Harris, and was reportedly located between aisle 28 and 29 of the stacks. Walking up and down the empty aisle impatiently, I couldn’t tell if I was hearing something new or if it was a combination of the Cones’ staticky, wailing wind, and the Periodic Table of Black Revolutionaries’ warm buzzing. Someone eventually came to my aid, confirming that, yes, there was an installation here. There were speakers set up at the very top of the stacks in each of the 4 corners of the aisle, playing a deep, low, quiet bass note. It was the kind you have to stop and sit with to hear it; felt in your body as much as heard in your ears. I appreciated this simple solace, standing in the middle of the dark aisle.

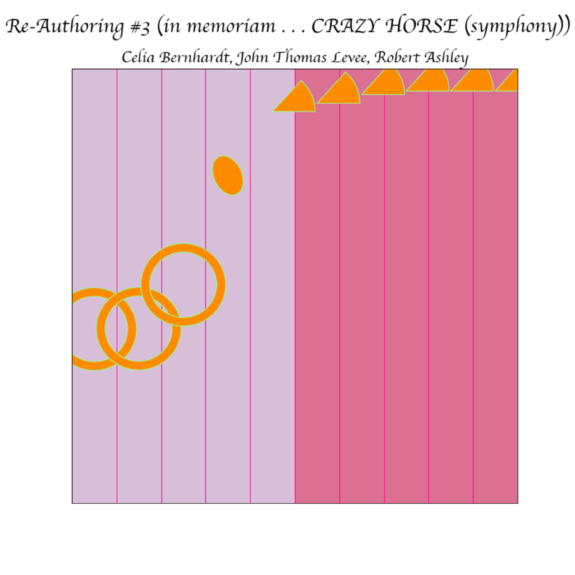

The last installation I saw was a participatory process called Re-Authoring Event #1 (Columbia University), created by John Thomas Levee. This piece grappled with elitism and graphic scores; I had no idea what these were, but John explained them to me as sheet music which did not use regular notation, but visual elements that were up to the musician’s interpretation. Columbia holds a select number of graphic scores in such high esteem that they cannot be circulated at all; no one can check them out of the library to use. John took a stack of those precious scores and had us play our interpretation of any one of them on a kazoo. His program measured the biodata from our kazoo playing (I believe this included warmth, humidity, and breath power) and converted it into a brand new graphic score, which we could create with 5 colors of our choosing.

I was exceedingly bad at playing the kazoo through a mask, and what came out was neither kazoo-like nor voice-like; more like the sound of pure humiliation. Still, I played for as long as I could handle and earned a pink and orange score for it. John was encouraging throughout the process. Upon a guest asking about the motivations behind the project, he mentioned that all the pieces kept above circulation at Columbia were all written by white men, and that the field of graphic notation at large remains dominated by this demographic. In this process of re-authoring these exclusive pieces, we were circulating them in a new way, bringing this art form into a world of accessibility, equity, and collective creativity.

We pocketed the kazoos and took them with us, so as not to spread germs.

The show was a quiet, subtle event for the time I was there. I don’t know that there was any particular theme stringing the pieces together—they clearly all took varying types of inspiration and levels of labor. The disjointedness kept me on my toes. It was a pretty wonderful introduction to sound art for someone who knew nothing about it before walking through the door.

I lingered for another minute after Re-Authoring, checked the list to ensure I’d seen everything there—I had the nagging feeling I could have missed something, which was entirely possible—and then set out for home. Walking through the impossibly dark dusk that’s now attacking New York, as the sun sets earlier and earlier, I appreciated, even more, the weird, otherworldly oasis that I had just been able to experience.

All photographs of installations via Celia Bernhardt

Original score of In Memoriam… Crazy Horse via occiciwan

Re-authored score via John Thomas Levee

0 Comments

0 Comments