On Thursday, April 21, Zuckerman Institute presented “Embracing Uncertainty: The Power of Curiosity and Exploration in Learning,” the fourth and final lecture of this year’s Stavros Niarchos Foundation Brain Insight Lecture Series.

Moderated by Associate Research Scientist Jennifer Bussell, the panel featured Professor Jacqueline Gottlieb and Professor Lisa Son. From the perspectives of both psychology and neuroscience, they discussed the importance of embracing uncertainties and taking risks.

Dr. Lisa Son, Professor of Psychology at Barnard College, was the first to share her insights. In her speech titled “Metacognition and Masks”, Professor Son discussed how “masks” are the greatest disruptor of metacognition.

Professor Son began with observations from an experiment with monkeys. When asked to put four random pictures in order, they were bewildered and, when the opportunity presented itself, pressed down buttons for hints. The moral is simple: even animals know to ask for help when dealing with uncertainties.

Humans are also information seekers who look for guidance and assistance in the face of difficulties. When Professor Son had a flat tire, she reached out, in a short period, to her insurance company, the nearest gas station, and her husband. But just as Professor Son would never call her children, we are selective in whom we ask for help. In Professor Son’s words, we enjoy “a skilled approach to curiosity.”

Why are we curious the way we are? The answer is metacognition. There are many definitions of the term, and Professor Son focused on three facets of its scientific framework: self-reflection, monitoring and control, and mental time travel.

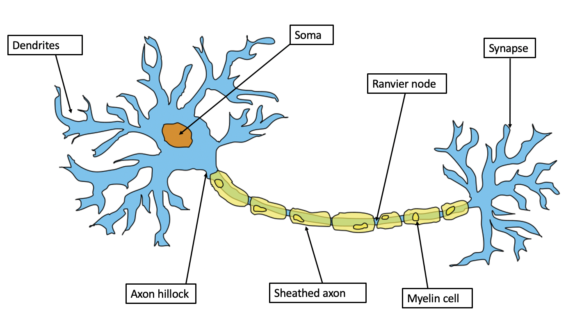

To understand self-reflection, think of a neuron checking itself in a mirror. Maybe after a glance at its dendrites, the little thing decides that its hair is not right. Naturally, it will ask a follow-up question: where can it find a brush? In this case, the initial assessment leads to appropriate behavior. Cognition behaves in the same manner, and such a cause-and-effect relationship makes up the second part of metacognition’s framework – monitor and control.

And what about mental time travel? According to Professor Son, this can mean either one of two things. On the one hand, we are able to travel linearly to the future to predict a result. For students who have exams coming up, mental time travel can help them decide whether they should start reviewing right away or procrastinate some more, as they measure their cognition and memory retention in the future. On the other hand, mental time travel can also mean traveling back to the past, the only difference is that this trip is circuitous rather than linear.

Indeed, our monitoring of the past is far from accurate. In what is known as the hindsight bias, humans, after learning about a certain outcome, tend to believe they have predicted the outcome in the first place. Before Alpha Go’s match again the champion Sedol Lee, Professor Son was convinced AI stood no chance against a human grandmaster. But after Lee’s defeat, hindsight bias convinced her Alpha Go’s victory was never in doubt – how could the human brain rival the computation power of artificial intelligence?

One consequence of hindsight bias is that it makes us diminish our achievements. It creates a thin “mask” that prevents us from recounting the truth instead of our tainted view of the truth. The people who wear these masks are known as imposters, who suffer from diminished curiosity and are afraid of being found out as frauds.

Sadly, “impostorism” is a prevalent phenomenon. People of all ages, races, cultural backgrounds, and expertise are haunted by the anxiety that they are not as competent as they appear to be. In their attempt to be perfect, they fear judgment, mistakes, and even success and acknowledgment. So great is their apprehension that they mask the metacognitive control strategies: they end up working alone, missing out on opportunities, help, and rewards.

We can easily reverse this negative feedback loop by utilizing good control strategies. The next time we find ourselves in a difficult situation, we can ask for hints, guidance, or more time. The only problem is, while such metacognitive control extends the period of our curiosity, it also “opens up a can of worms,” which reveals imperfection or failure, the greatest enemy of an imposter.

Thus it seems one cannot easily take off this “genius” mask on his own; he needs society’s help. Professor Son believes it is up to the “adults” to take off their masks first and exhibit good metacognition. Hearing someone we respect admit their limitations put us at ease, and listening to their past detours is a great way to foster a metacognitive culture. That is the power of role-modeling curiosity: it dissipates the irrational discomfort associated with uncertainty.

To close off her speech, Professor Son stressed that not all masks are bad: only the imposter masks are detrimental. Once we get rid of those, “all we will be left with are the fun ones.”

Building off on Professor Son’s captivating talk, Professor Jacqueline Gottlieb of the Columbia University Department of Neuroscience shared her opinion on the matter. In her speech titled “Uncertainty Deep in the Brain,” Professor Gottlieb discussed how metacognition is deeply woven into both our consciousness and unconsciousness.

Every waking moment of our lives, metacognition is busy at work, monitoring the brain’s state and making decisions about how to allocate its resources. With modern technology, we can study these conscious and unconscious mechanisms that have revealed their neural substrates in the brain.

Professor Gottlieb played a video of an ordinary waiting room in a science laboratory. The audience was asked to spot if any items were out of place. Now, I was not unfamiliar with the purposes of these kinds of videos – your attention is fixed on something trivial (say some people juggling balls) that you somehow miss absolutely bizarre things (say a man in an ape suit running across the screen).

So there I was, trying to discern which piece of furniture or decoration was out of the ordinary while secretly watching out for men in gorilla suits. Yet I was completely oblivious to the fact the pictures were not static – little by little they blurred and changed until in the end everything in the original picture morphed into something else.

This perfectly proved Professor Gottlieb’s point. We feel as if we see everything, but the reality is our small brains cannot fully comprehend everything that is going on in this big world. “It is really an existential dilemma,” said Professor Gottlieb. To cope with this vast amount of information, humans have developed selective attention – the ability to pick very few things from the environment and use them to structure the reality around them. This mechanism is beautifully displayed in our eye movement, as we shift our gazes from one detail to another.

Such a shift of attention can also be considered “mini-curiosity.” When we are drawn to something, we control our visual system to find the answer to the question “What is that?” And when we are not totally clueless when we ask that question; we possess some level of knowledge or partial knowledge. It is this partial knowledge that motivates curiosity. If we are asked a very arcane question, say “In which U.S City is the Public Transit System known as RTA?” so little do we know about the topic that we would not be bothered to find out the answer. However, if the question is “Who wrote Charlie and the Chocolate Factory?” we would want to get down to the bottom of it because we feel the answer is at the tip of our tongue.

If we look at this engaging process in the context of our brain, the temporal cortex holds all our knowledge (and partial knowledge, for that matter). After processing new visual information through the temporal cortex, a signal is sent to the frontal cortex and translated to the feeling we know as confidence.

But confidence is not enough to spark actions: the brain needs to turn it into motivation. This is performed in the anterior cingulate cortex by monitoring the level of Dopamine and releasing Norepinephrine which controls arousal. Combined, the cortex and the chemicals carry out what is known to economists as the cost-benefit analysis. Such analysis is crucial because, as Professor Gottlieb pointed out, different information has different values. All information can be divided into two categories, instrumental and non-instrumental. The former is a means to an end, while the latter is a goal in itself.

To sum up her talk, Professor Gottlieb reminded us that attentional “mini-curiosities” are the brain’s tools for investigating the world, generated based on previous knowledge, external rewards, and intrinsic motivation. With it, the individual can make complex decisions; society can reach important conclusions; and artificial intelligence can create autonomous agents. In a word, curiosity helps us navigate the world much more easily.

Images via Pix4free, Wikimedia, Pixabay, and Anatomy Info

0 Comments

0 Comments